Urbino is a game with a thin veneer of a theme provided to make the gameplay more approachable for a general audience. Yes, the rules state it’s about Architects building “the most vibrant and most valuable districts” but don’t let that fool you. This is an Abstract plain and simple.

That fancy language about vibrant and valuable districts simply means the goal of the game is to build areas of buildings worth more than your opponent by the end of the game.

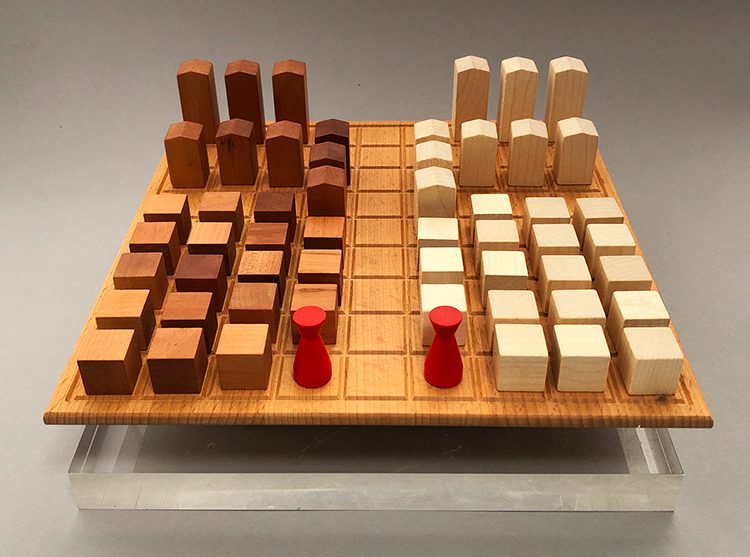

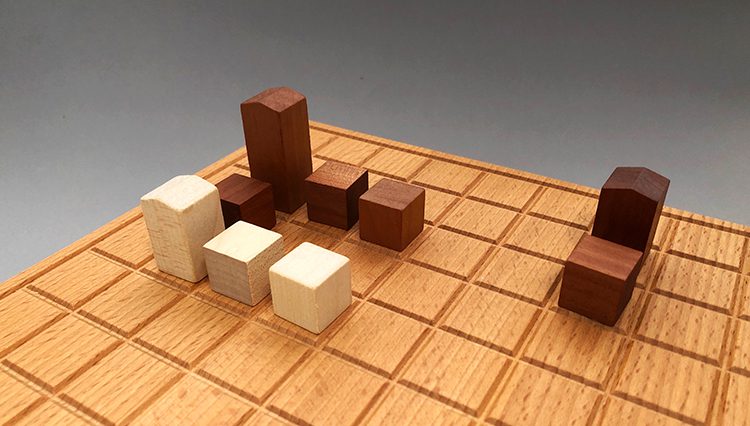

We’ll get to that in a moment, but first, take a look at the board and these pieces.

Allow me to state the obvious: Urbino is a simple but beautiful game to play. The wooden pieces come in three different sizes and are lightweight; they just feel good to hold in your hand while you contemplate your next move. As you build your cities, the board takes on a very pleasing character, making playing the game even more enjoyable.

Playing the Game

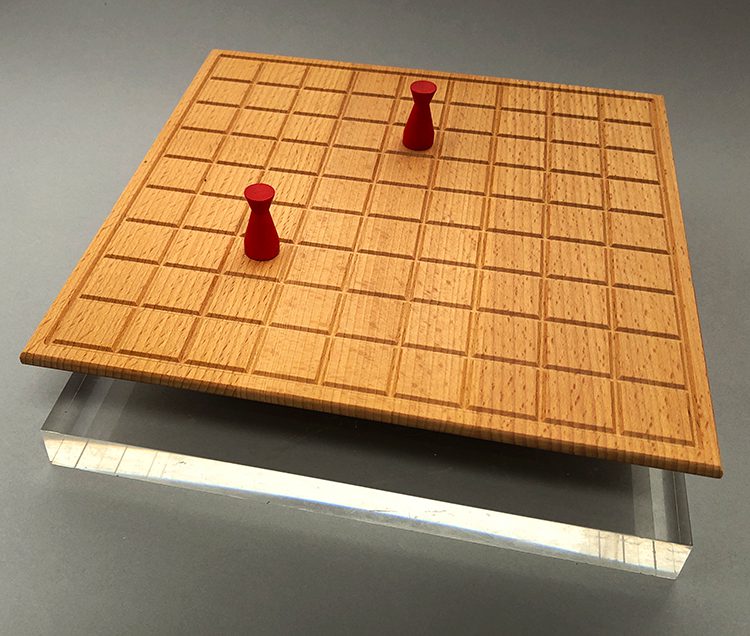

The game starts with each player placing one of the red tokens, or Architects as the game refers to them, on the board. Once initially placed on the board, Architects are not ‘owned’ by either player; either player can move either Architect on their turn.

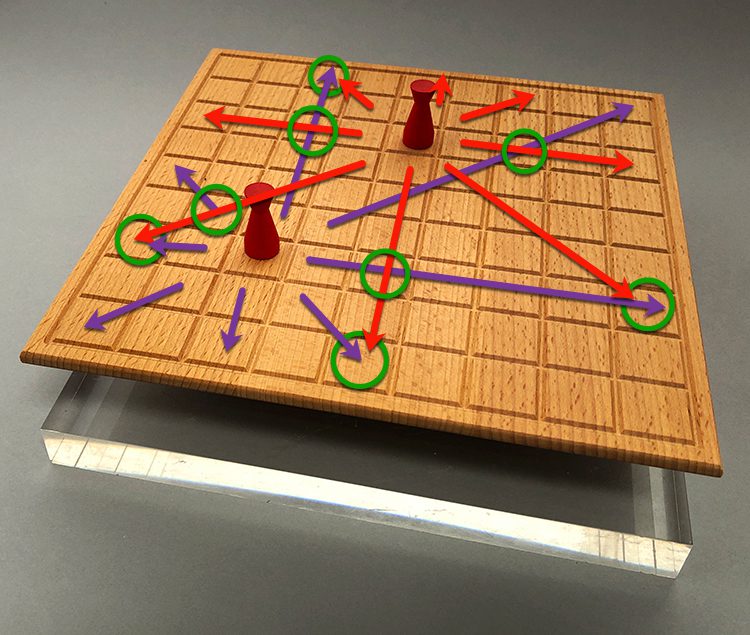

A turn starts with a player moving one of the two Architects to any unoccupied square on the board within ‘sight’ of the other Architect. ‘Sight’ in Urbino works strictly along the orthogonal and diagonal lines stretching out around each architect.

You’ll then survey the board to see where a player can build one of their structures. By looking orthogonally and diagonally, you’ll need to locate open squares that the two Architects can both ‘see’. These are the locations on the board you can choose to build on.

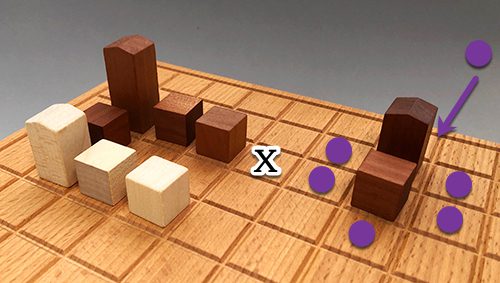

So, for example, after each player places an Architect on the board at the start of the game placed like this at the start of a game…

…the first player has a line of sight of eight options for placing a structure.

On each subsequent turn, the active player may choose to either leave both Architects where they are or move one Architect to any open square on the board. Then, locating an intersecting line of sight square, the player places a building of their color on the board.

Each player has three different types of buildings. Simple squares are Houses, the pieces that are twice as tall with an angled top are Palaces, and pieces three times as tall, also with angled tops, are Towers. Each player has 18 Houses, 6 Palaces, and 3 Towers in their supply.

When it comes to the end of game scoring, Houses are worth one point, Palaces are worth two points, and Towers are worth three points.

Line of Sight

There are, of course, squares that one Architect can see and the other cannot see.

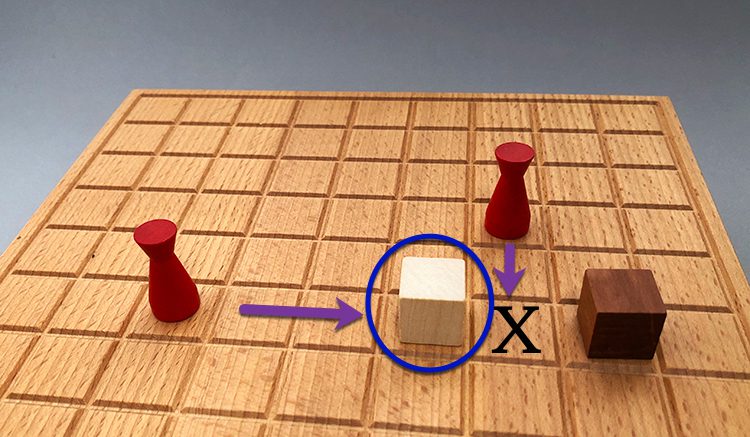

Take, for instance, this simple example:

f

While there are still many other squares both Architects can ‘see’ from where they stand, the square between the existing Light and Dark pieces is not one of them. The Light building is blocking the view of that square.

Blocks and Districts

A group of orthogonally connected buildings is called a Block. When both players build orthogonally adjacent to each other, their two combined Blocks become a District. This is important for two reasons:

- Blocks that are not part of a District are not scored

- No two Districts can ever be orthogonally connected

Blocks and Districts can be made up of buildings of any size with the following restriction: Towers of either color cannot be orthogonally adjacent. The same holds true for Palaces. (There is no such restriction for Houses.)

Since Districts are the units scored at the end of the game there is an important rule governing their construction: each District can only have one connected Block of buildings of any given color.

To better explain this concept, take a look at this scenario:

Dark has an opportunity to join their District on the left with the Block to the right to create one large District.

Light, of course, would like to prevent this.

In order to stop Dark from joining the District with the Block, Light would need to place a building somewhere to prevent this.

The X on the example above indicates a spot where Light cannot place a building. This would create two Light Blocks within the same District, which is not allowed.

Instead, Light could place a building on any of the spaces indicated by a purple dot. By placing a Light building on any of these spaces Light would create a separate District.

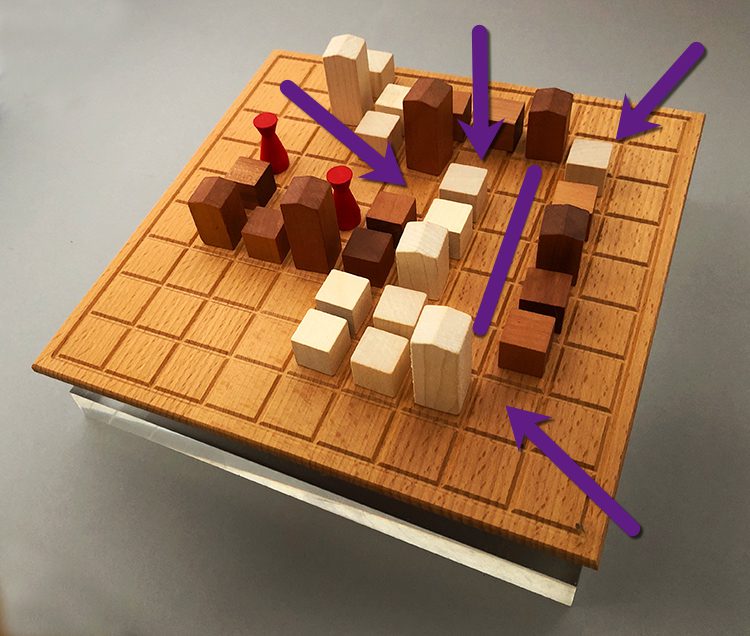

Here’s another example of Districts taken from a different game.

Here is an example board with three Districts, each labeled separately so you can see the different borders of each.

Because Districts can only have one Block of each color, during the course of a game there will be squares on the board that new buildings cannot be placed on.

Viewing the example of the three Districts above, here are the squares that cannot be built upon.

If either player placed a building on any of the indicated squares they would be adding a second, illegal Block to a District.

End of Game and Scoring

If a player can make a move, they must.

A player must pass if they are unable to move one of the Architects in such a way that they can legally place a building. Providing the other player can place a building the game continues, with the passing player able to continue playing as soon as a move is available to them.

When both players pass consecutively, the game is over and scoring begins.

To start scoring, any Blocks of a single color are discounted. Only Districts are scored.

As previously mentioned, Houses score 1 point, Palaces score 2, and Towers score 3.

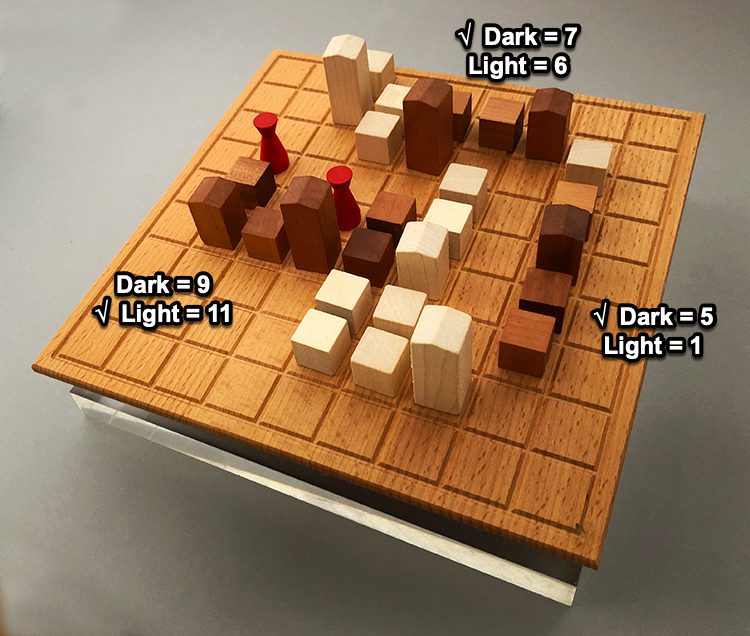

Let’s take another look at the example you’re already familiar with. Despite there still being additional moves that could be made, here is how the game currently scores.

The final tally only counts winning scores for each district. So in the topmost District, Dark scores 7 points. Light’s 6 points are not counted.

In the two Districts Dark wins, Dark scores 12 points (7+5). Light takes the largest District with 11 points. This means the score currently stands at 12-11 in favor of Dark.

Ties are settled by looking at who has played the most Towers, then Palaces, then Houses. This gives you even more incentive to make sure those Palaces and Towers get out on the board in Districts that you dominate.

Thoughts and Impressions

The friend I played Urbino with and I learned to appreciate the depth of the game over several weeks. In each session we learned more about the strategies of the game and, as a result, our games became closer and closer.

Players need to pay close attention to the constant struggle between making offensive moves to score points and defensive moves to keep their opponent from scoring points. Most Districts will be fought over in skirmishes of back-and-forth building, adding Palaces and Towers to quickly run up your dominance over the District. At some point, however, it becomes apparent that one player will have won the fight — but not necessarily the battle. A clever opponent can build up a block nearby to sneak into the District… if the District’s owner isn’t carefully building their own defensive perimeter.

That being said, building onto a District you already dominate with a Palace or a Tower late in the game is a good way to score extra points. Just make sure you aim and time these plays carefully: a move that builds your points without claiming ground is a chance for your opponent to advance on your territory or defend their own.

The most important aspect of Urbino comes down to where to place the Architects. At first glance, their placement only determines where you can place a building on your turn. However, that placement also provides the starting position from which your opponent may choose to move an Architect on their turn and where they can build. I lost several games because I wasn’t paying attention to how my opponent could move an Architect to his advantage.

Each move of the Architects then becomes a trade-off, once again balancing offense with defense.

After our first few games my friend and I agreed that Urbino had surprised us. Instead of just a simple building game, Urbino had depth and complexity. We played for six Thursday nights in a row. Highlights included me realizing that I had the majority of the points on the board and could play the Architects into a corner and force a very early ending to a game (provided my opponent wasn’t paying close attention to the Architects), and a game that was a tie in points was broken by one player who built more Palaces than the other.

If you appreciate Abstract games the way I do, I encourage you to give Urbino a try. It’s easy to teach, easy to learn, and will be a challenge each time you bring it to the table.

Add Comment