They don’t publish many auction games nowadays, do they? When was the last time a new through-and-through auction game was given a high profile release? Ra just received a lovely reprint from 25th Century Games, but that’s a reprint—the original game is from 1999. There have been plenty of games with auction elements, but a quick consultation of BGG confirms that auction games, your For Sales and Modern Arts, don’t get printed anymore. The only one I can think of from the last several years is Amabel Holland’s charming Watch Out! That’s a Dracula!, a freebie included with orders placed during Hollandspiele’s annual sale.

This is a shame. I love auction games. I love them for the same reason that I love trick-taking games. There’s an inscrutability to what’s going on. There are precious few objectively correct decisions. It’s all vibes, man. It’s all tension, too. When do you call your opponent’s bluff? Can you push them to spend a little more? Can they push you to spend a little more? Is whatever McGuffin you’re bidding on worth it? Nobody knows. I’ll never understand how auction games fell so fully out of style.

Tent Revival

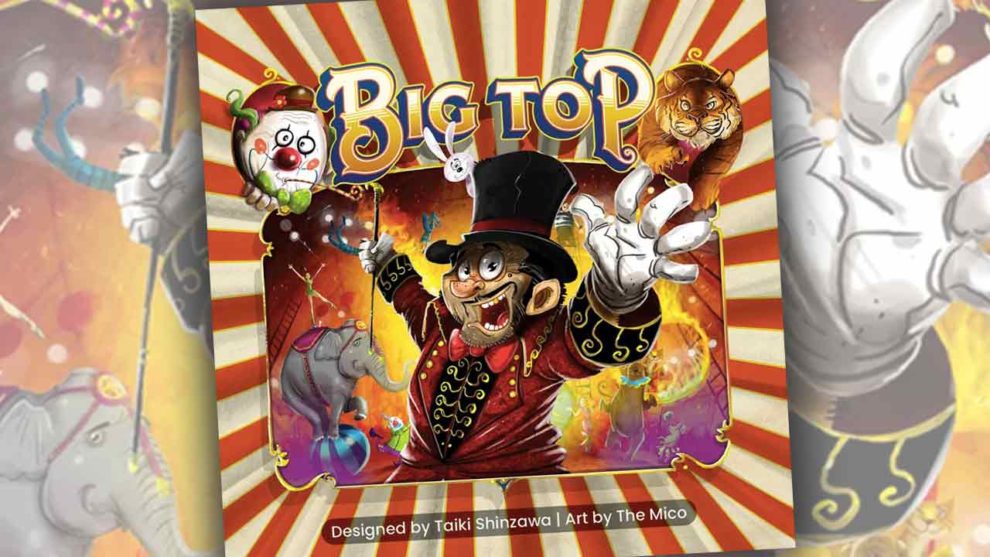

Big Top, from designer Taiki Shinzawa and publisher Allplay, is an auction game in the classic vein. A consortium (a cartel?) of circus managers come together to buy and sell talent contracts, represented by cards with vibrant illustrations from artist The Mico. Each player starts the game with one card in hand. The active player draws a second card from the deck, choosing one of the two to put up for auction. Going around the table, players take turns bidding or passing, until only one buyer is left.

If I win your card, if I buy out your contract with the Fire Eater, I pay you. If you end up winning your own card, renewing the contract, you pay the supply. The card gets placed in front of your player screen, where everyone can see it.

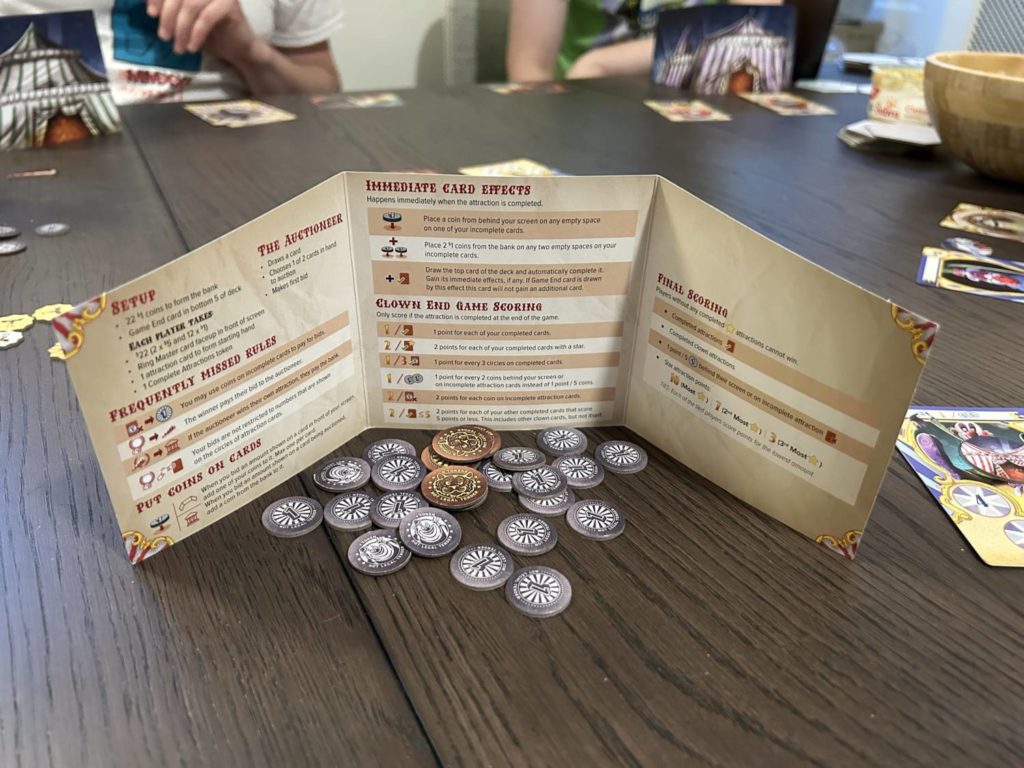

That’s when it starts to get weird. It’s actually been weird the entire time, but I didn’t tell you. Every card has a series of numbers in circles. Here’s an example:

The values in those circles, and the number of circles, will change, but they all follow the same basic principle. When you place a bid, if the value of your bid matches a number on any of the cards in front of you, you take a coin from behind your screen and cover a corresponding circle on each card showing that value. The same applies for the card up for auction. In that case, the coin comes from the bank, not the player.

While all the cards in Big Top will score you points in various ways, they are each and every one of them absolutely worthless until every circle has been covered with a coin. This can create some fun dynamics around the table, as people try to balance bidding to hit their own marks with what I’ve come to call spite bidding, bids calibrated to prevent your neighbor from finishing off a card in front of them.

Big Top is the first auction game I’ve ever played where the values of your incremental bids matter just as much as the value of the winning bid. It’s a really interesting idea. Like Shinzawa’s trick-takers (Cat in the Box, 9 Lives, Ghosts of Christmas), Big Top is asking a question no design I’m aware of has asked before. Whether or not you believe he has created any great games, he is a great designer.

And In This Ring…

Big Top is good. It is not great. It is a difficult game to get up to speed, and the momentum is precarious. In part because of that, Big Top goes on for much longer than it should, about twice as long as you want it to. That’s not so good. The beauty of the circus is that it rolls into town, plays one night only, and leaves just as quickly as it arrived.

Add Comment