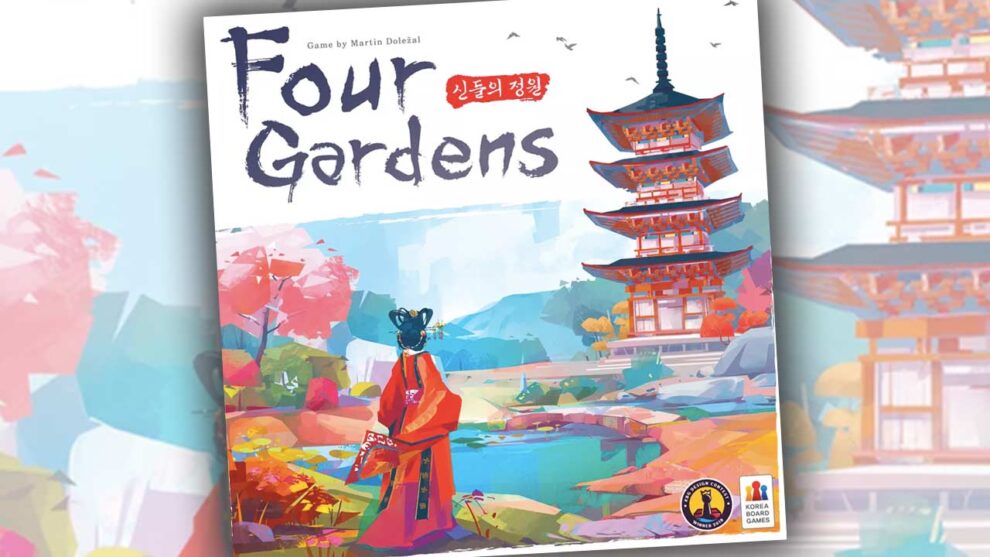

As a fan of the game Tokaido—a game where one of the things you are trying to do is to create these beautiful panoramas—when it was suggested that I check out the game Four Gardens, where panoramas are the focus, I jumped at the chance! Of course, when an aspect of a game shifts to become the entirety of a game, the mechanics will become a bit more involved. This is as it should be. What is needed, however, is for the process to result in a proper payoff. Does Four Gardens deliver?

Setup

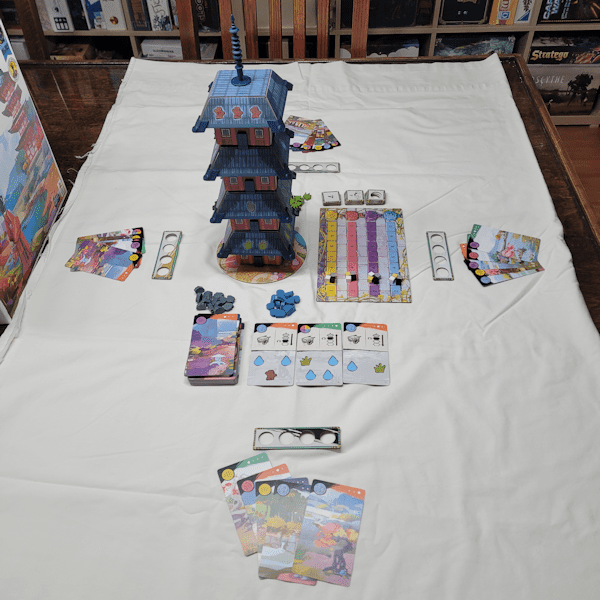

The central feature of Four Gardens is a four-level pagoda that needs to be assembled before you can play. This only takes a few minutes. The instructions are clear, and when you are done (despite the size of this thing), the pagoda stores easily within the box thanks to a fairly well designed insert.

When playing, the pagoda is a presence! It dominates the table in the early game, and there is rarely a moment when the players are not looking this thing over, because the central mechanism of this game is dependent upon this feature. The pagoda is not something that is there just to be there and look pretty (like, for instance, the Evertree in Everdell). The pagoda is a pretty feature, but it is also functional; it is the source of your resources.

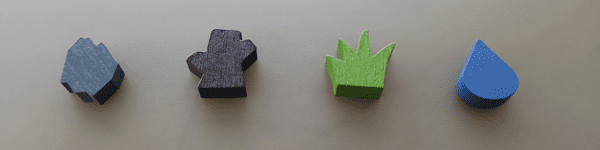

On each level of the pagoda are icons for one of the four resources in the game: plants, stone, water, and wood. The pagoda has four sides; each side has 0, 1, 2, or 3 icons of the resource associated with that level. At the start of the game, the layers of the pagoda are assembled in a random order (i.e., plants could be the top level, the bottom level, or one of the middle levels; this changes from game to game).

Once set, each layer of the pagoda is rotated to place the number of icons on each level into a standard starting position. First, locate the side of the pagoda where the bottom layer has three icons. Rotate the level above it until that layer has two icons. Rotate the layer above that until it shows one icon. Finally, rotate the top layer until it shows zero icons.

The other components of the game are:

- Resource Tokens ×60

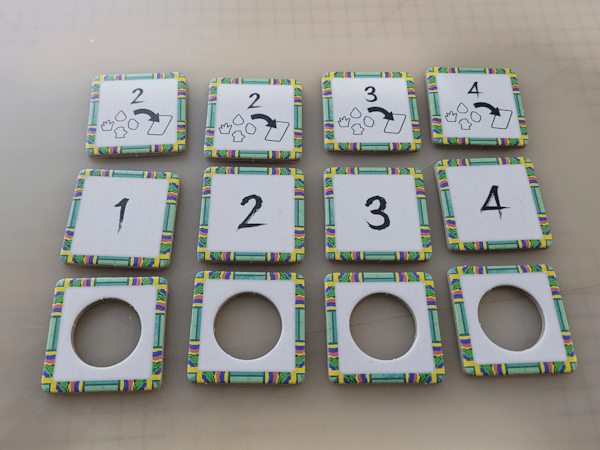

- Planning Tiles ×4

- Bonus Tiles ×12

- Scoreboard

- Score Markers ×16

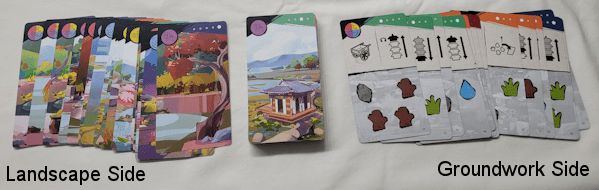

- Cards ×70 (two-sided: landscape on one side, groundwork on the other)

The four resources in the game are stone, wood, plants, and water. There are 15 of each resource token. These should be placed near the pagoda in areas where all players can reach them.

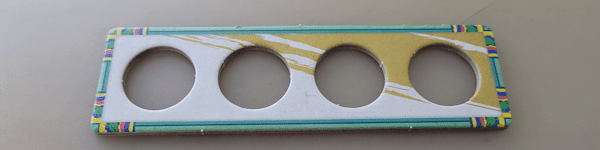

Each player starts the game with a planning board that can hold up to four resources. Players start the game with no resources.

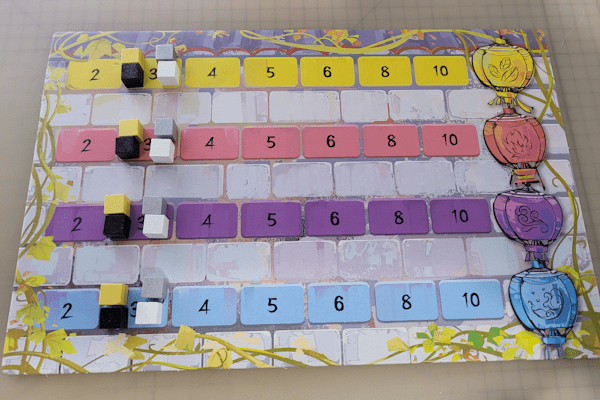

Each player has four scoring tokens. The players start with their scoring tokens on each of the 3-point spaces of the scoreboard.

Each player is dealt five cards (landscape-side up; other players are not privy to the groundwork information on a given player’s cards). Three cards are dealt groundwork-side up to form the market. The remaining cards form a draw pile, landscape-side up.

Off to the side, all the bonus tiles should be arranged in three stacks. For two of those stacks, the top tile should have the highest number, and then it should work its way down from there. The third bonus tile has no numbers and stacking order is not important.

At this stage, setup is complete and the game can begin.

Playing Four Gardens

Below is a brief summary of gameplay. Below that is a detailed look at how the game is played. Click on the link and you can dive into the details. If you just want a summary of the game-play, just read this next section and skip the details.

Summary of Gameplay

Starting with the first player and going clockwise, each player can perform three actions. They have four actions to choose from and can perform the same action multiple times. Players can:

- Lay Groundwork: place a card from their hand into their play area to start the groundwork for a new landscape.

- Rotate and Collect: place a card from their hand into the discard pile to rotate a portion of the pagoda and gather resources, placing them onto their planning board. This action can only be taken if the card indicates that this is an available action. The card discarded indicates which level(s) of the pagoda rotate, and whether resources are gained starting at the top or the bottom of the pagoda. Once a player’s planning board is full, they cannot gain more resources.

- Take a Wild: place a card from their hand into the discard pile to take any one resource from the supply and place it either on their planning board or directly onto an active groundwork card. This action can only be taken if the card indicates that this is an available action.

- Reallocate Resources: place a card from their hand into the discard pile to reallocate their resources. Resources can be moved from the planning board to an active groundwork card, from the planning board back to the supply, or from one active groundwork card to another active groundwork card.

Players are limited to three active groundwork cards at any given time. When a groundwork card receives all the resources it needs, it is immediately converted into a landscape and scored. The player moves their scoring marker up one space on the track of the god indicated on the card. Additionally, any other previously completed landscape cards for that panorama score again. If a player’s score marker is on the 10-point space and they score again for that god, all other players are moved back one space on the track. If a player is moved backwards from the 2-point space, their scoring marker is removed from the track, and the game (they can no longer gain any points for that god).

If a panorama is completed when a card is converted, then the player gains one bonus tile: bonus points, bonus resources, or an extension of their planning board. Each type of reward can only be gained once.

The end of the game is triggered when a player completes a set number of landscape cards (8 in a four-player game, 9 in a three-player game, 10 in a two-player game). The game continues until all players have taken the same number of turns. The player with the most points at the end of the game wins.

Detailed Look at Gameplay

Starting with the first player and going clockwise, each player can perform three actions. They have four actions to choose from and can perform the same action multiple times. Before we get into the actions, however, we need to understand the information that is on the groundwork-side of a card.

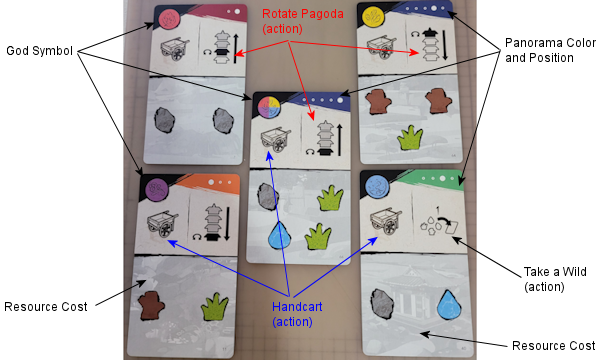

The top-left corner has a symbol that indicates the god (red, yellow, purple, or blue) that will be pleased by the card if it is converted from groundwork to a landscape (see below). This means that you score on that god’s track if the card is converted. Some cards have a multi-color god symbol here, meaning that the player can score on any one of the god tracks when this card is converted.

The top-right corner shows the panorama to which the card belongs (maroon, orange, green, or dark-blue) as well as which position that card goes. The maroon panorama is made up of two parts, and so there are cards for each of those two positions. The orange panorama is made up of three parts, the green panorama is made up of four parts, and the dark-blue panorama is made up of five parts.

Each card can be played as a groundwork (hoping to be converted into a landscape), or it can be discarded for one of the two actions at the top of the card. All cards have a Handcart; all cards can be used for the Reallocate Resources action. The second action on the card is either Rotating the pagoda and Gathering Resources, or the Take a Wild action.

The bottom of the card shows the Resource Cost for converting the card from groundwork to a landscape (see below; it is coming soon, I promise).

So, now that we know what information is on the card, let’s talk about what you can do on your turn.

As indicated above, on a player’s turn, they take three actions. They may take any combination of the four available actions (even taking the same action multiple times). The actions are:

- Lay Groundwork: place a card from your hand into your play area, groundwork-side up. A player cannot have more than three cards in play that are groundwork-side up. A player cannot place a card into their play area if they already have a card in their play area with the same panorama color and position (e.g., at no time can two cards that are orange panorama position two be in a player’s play area, even if one has already been converted to a landscape).

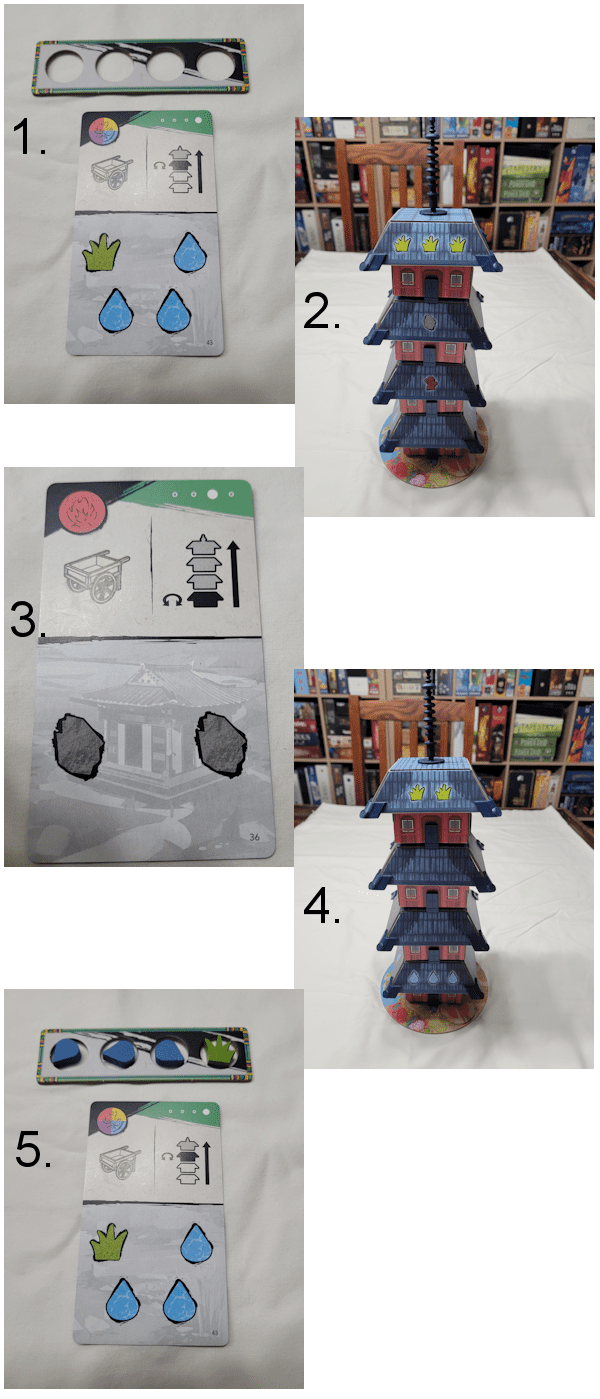

- Rotate and Collect: place a card from your hand into the discard pile. That card must have the pagoda symbol on the right-side of the two action spaces (see the Rotate Pagoda elements in the image above). Rotate the section(s) of the pagoda indicated in the image and you may rotate 90° clockwise or counter-clockwise. When rotating, the card will indicate which section of the pagoda can be rotated. All sections above are also rotated. After rotating, there is an arrow next to the pagoda symbol that indicates whetheryou gather resources from the top-down, or from the bottom-up. The player must collect all resources shown on their side of the pagoda at a given level before they can collect resources from the next level. The player’s planning board can only hold four (4) resources. If the planning board becomes full, then no more resources can be acquired.This is a bit confusing when describing it, so let’s look at an example:

- The black player starts their turn with no resources and an active groundwork card that requires three water and one grass.

- They look at the pagoda and see that they have three plants, one rock, one wood, and no water facing them.

- They look in their hand and see a card that has the Rotate and Collect action shown. This version of the action indicates they rotate the bottom of the pagoda (including every level above it) and collect resources from the bottom up.

- They rotate the bottom of the pagoda 90° counter-clockwise. This will reduce the values of each level by one, except the water which will rotate from zero to three resources! Since they are collecting the first four resources they encounter, working from the bottom up…

- …they are able to get three water, zero wood, zero rocks, and one plant (if they had a fifth space in their planning board, they could have gotten the second plant, but they do not). This is exactly what they need to complete the groundwork card and turn it into a landscape! Their next action will likely be one to Reallocate Resources (see below).

- Take a Wild: place a card from your hand into the discard pile. That card must have the take-a-wild symbol on the right-side of the two action spaces (see the Take a Wild element in the image above). The player takes one resource of any type from the supply, and either adds it to their planning board or places it directly onto one of their active groundwork cards where that resource is shown.

- Reallocate Resources: place a card from your hand into the discard pile. Since all cards have the Handcart symbol on the left-side of the two action spaces (see the Handcart elements in the image above). This action allows the player to move their resources around in any way desired. Resources can move from the planning board to an active groundwork card, from the planning board back to the supply, or from an active groundwork card to another active groundwork card.

At the end of any action, if an active groundwork card has all of the resources it needs to be converted to a landscape, it is. Return the resources on that card to the supply, and flip the card over. Landscape cards do not have to be completed in any particular order (e.g., you can complete the third position of the green panorama before completing the first or second positions, and so on).

And this is when we get to the absolutely delicious scoring system that Four Gardens uses!

When a card is flipped from groundwork to landscape, the player moves up one space on the indicated god’s scoring track. Additionally, any landscapes that are a part of that same panorama that were converted prior, score again!

For example, if a player completes the third position of the dark-blue panorama scoring for the red god, then completes the fifth position of the dark-blue panorama scoring for the purple god, the third position of the dark-blue panorama will score again, moving them up on the red god’s scoring track again! If they then complete the second position of the dark-blue panorama scoring for the blue god, the third and fifth positions will both get scored again, and so on.

If a card is flipped to landscape and indicates a wild (the multi-color god symbol), the player can score on any of the four god tracks. If the card scores multiple times, then each time the wild-god symbol can be used for any god, not just the one it was used for initially.

Now, take a good look at the scoring track. There are seven spaces on each god’s track. These spaces score 2-3-4-5-6-8-10 points. If a player’s score marker is on the 10-points space of a god’s track and scores that track again, then every other player moves backwards one space on the track (even if they, too, were on the 10-point space). As if that were not viscous enough, if a player is moved backwards from the 2-point space, their scoring marker is removed from that track; that marker cannot return to the scoreboard for the rest of the game. The player will score zero for that god.

If a player converts a groundwork into a landscape and that completes the panorama (two landscapes for maroon, three landscapes for orange, and so on), in addition to scoring as above, they are also able to select one of the bonus tokens.

There are three types of bonus tokens. They are:

- Take Wilds: the player takes the top token from the stack. The token has a number (4, 3, or 2) and the take wilds symbol. The player gathers a number of resources up to the value shown from the supply, and places each into either their planning board or onto active groundwork cards in their play area. If this completes a groundwork, then flip it and score just as above.

- Bonus Points: the player takes the top token from the stack. The token has a number (4, 3, 2, or 1). The player places this in their play area. This represents a number of bonus points they will gain at the end of the game.

- Planning Tile Expansion: these tokens just have a frame and a hole. The player places the token next to their planning board, giving them a fifth resource they can collect and store.

A player cannot have more than one of each of the bonus tile types.

The game continues until a player has converted a set number of groundwork cards (8 in a 4-player game, 9 in a 3-player game, or 10 in a 2-player game). Once this happens, play continues until each player has had the same number of turns. Time to score up!

A player’s score is the total number of points they have in the four god tracks on the scoreboard, plus any points they received from bonus tiles. The player with the highest score wins.

Beauty

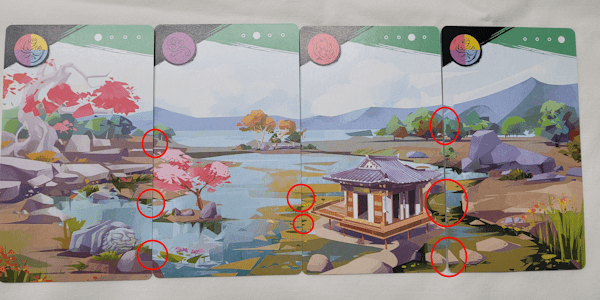

One of the things you have to do if you are going to make a game about panoramas is to have some beautiful artwork. And Four Gardens delivers! Each panorama is not only pretty and interesting, each one has multiple possible looks depending upon which cards are used to create the whole picture. The basic framework of the landscapes is the same, but they differ in the details. For example, here are two possible configurations for the orange panorama:

The first position may or may not have a stone fountain; the second position may or may not have a built up pathway; the third position may or may not have a small building in the background. This is a feature of the panoramas I truly wish Tokaido had!

The only thing that I can say by way of complaint about the beauty of these cards is that the elements from one card to the next do not always line up the way they should. A few of these oddities might be able to be explained away by how the cards are cut. Most of them, however, cannot. It is a minor point, but it is one that sticks in my craw.

Other things that create some oddities in the game include:

- Having a white player is fine when it comes to the scoring cubes; sort of odd when it comes to the coloration of the planning boards (see above).

- Having a yellow player and a yellow god seems off; when we were discussing please move yellow we often had to check to see which color of player was talking to make sure we were moving the correct piece on the correct track.

- There are three different shades of blue used in the game: the light-blue of the blue god, the medium-blue of the water resources, and the dark-blue of the largest panorama. There are other colors. I am sure that this could have been avoided.

- The bonus tiles are printed on both sides. This is not an issue except for the fact that the rulebook tells you to flip the Take Wilds tiles over to indicate that they have been used. When you flip them over, they just look the same, so this is kind of silly.

- There are 70 cards in the game. They are beautifully designed to take on multiple roles. The number of cards makes sense (four panoramas, five cards for each position in each panorama, and so on). But in the games we played, the number of cards seemed too low. In the two player games we played, we emptied the deck and re-shuffled once or twice; in the four player games we played, we lost count of how many times this happened. As the deck is thinned out with groundworks being turned into landscapes, it is untelling just how many of a given action might be available within those few remaining cards.

- The game ends when any player has a given number of landscape cards in play. This seems to me to be an unsatisfying and artificial timer. While playing, I was contemplating what the perfect game-end trigger for this game might be. I came up with a few ideas. I might experiment with a couple at some point. If I find one I like, I will write an article sharing that particular house-rule with you.

However, with all that said, the game is amazing!

And The Beast

I am an old-school gamer. I remember playing Dark Tower back in the 1980s and having a blast! The pagoda in the center of the table for this game has that same imposing presence, and I love it. When I am rotating the pagoda levels, it feels like those moments of tension when you can hear the gears in Dark Tower moving something unseen in its belly. It is not the same kind of tension, however. The tension in Four Gardens is far more palpable, stress-inducing, and wondrous.

The tension comes from the fact that the tower seems so simple and inviting. You look at the levels, and you know what you have currently, what will come with a twist clockwise or counter-clockwise. You know that when you see a bunch of icons, you are never going to be able to get everything there – you only have four (or five) spaces to store those resources.

When you need two water, it will invariably be blocked by a bunch of stones and plants. When you need three wood, it will be at the top of the tower, and all of your cards have you gathering from the bottom up. What seemed like a calming and beautiful pagoda suddenly becomes a demon-like entity keeping you from the things you really need. You look at the cards in your hand; you keep checking the adjacent sides of the pagoda. You look at which levels you are allowed to rotate and which direction you will be gathering resources. You are desperately trying to crack the code of the pagoda and your cards, like a safecracker in some old black-and-white gumshoe movie.

When you can do what you need to, you feel like you just ran a marathon. When you can’t, you start looking for alternatives. It’s Darwinian. Winning this game requires adapting to the situation. You adapt or you fail.

Add to this the fact that you can be completely removed from the sight of the gods, and suddenly you realize that things can be harrowing! It is a simple rule and it is presented in the rulebook without fanfare. If a player is moved backwards from the 2-point space, their scoring marker is removed from that track; that marker cannot return to the scoreboard for the rest of the game. The player will score zero for that god.

In a game where no player is capable of scoring more than 44 points, having one or more 10-point tracks made off-limits to you can feel like a knife to the chest. At the same time, pushing a player or two off that particular cliff is quite satisfying!

Four Gardens is a beautiful game that I can whole-heartedly recommend. The theme, gameplay, and scoring are perfect. But for a couple of minor production choices, and a game timer that seems a bit arbitrary, the game is truly flawless.

Add Comment