I’m a lucky man in so many ways…and when it comes to getting access to older games, my friend John came through once again.

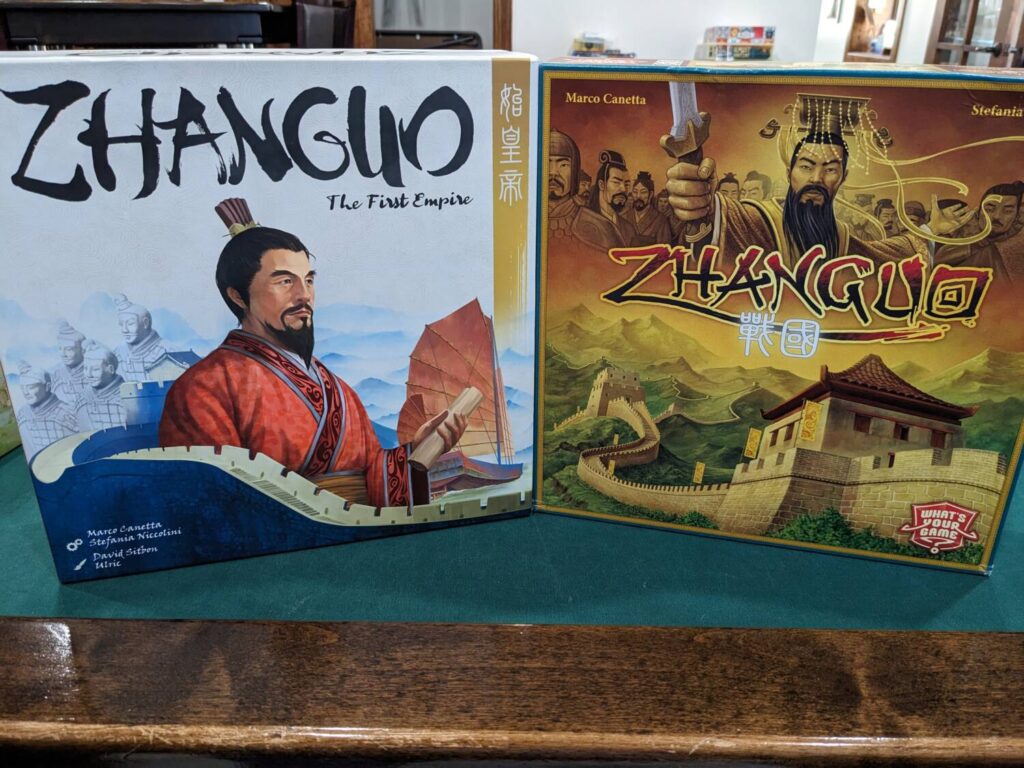

After I picked up a copy of Zhanguo: The First Empire (2023, Sorry We Are French) at Gen Con this summer, I wanted to try the original game, 2014’s ZhanGuo, to see what changes were made over the last ten years or so to bring the older game to modern audiences.

2014 wasn’t that long ago, but it feels like many publishers are digging up older games and giving them a somewhat-needed—or maybe, much-needed—facelift. I was excited to give the original ZhanGuo a spin. (Yes, the original game’s title had a capital G in the middle, which was changed to a lower-case G in the new version. While I’m guessing this was for historical accuracy, this change just means you’ll have to accept this minor annoyance for the purposes of this review.)

ZhanGuo (2014) is one of the heaviest tactical games I have ever played. That’s because it really is a strategy game—you’ll have to set out your goals almost before you begin to play, by studying the areas of the map that will pay out best between all of the randomized goals in each game—but a clever card mechanic dictates which actions you can maximize each turn.

In ZhanGuo, players are emissaries serving the first emperor of China more than 2,000 years ago. The goal is not simple—tasked with unifying five different regions through laws, language and measures, players have to balance an almost comical array of different things while also trying to keep unrest in each of the map’s five regions under control for 30 turns across five rounds. Points come from everywhere, but ZhanGuo is not a point salad—almost everything requires some planning in order to score.

John and I played ZhanGuo with another friend on the weekend before I began playing the new game. We all agreed: ZhanGuo had some balancing issues, and the production was pretty bland in terms of its look and feel. One of the actions felt like a waste, and the board’s Wall system was a little messy; the Walls (where players can build parts of the Wall of China, in order to gain access to end-game scoring milestones) were a little scattered and accessibility was a bit of a miss.

I personally thought one of the systems felt broken, where players would earn tokens that could be spent at the end of a round to gain rewards. It felt broken because if a player chose to not take a reward, they could keep all of their tokens for the next round. This mechanic really stifled the ability to earn tokens in successive rounds.

John made an interesting comment after playing it. Basically, he said that he “bought this game years ago, and played it once, but never felt the need to play it again.” We thought there might be a good game in there, but the 2014 finished product really needed some refinement.

Upgrade Confirmed

With that lead-in, I got Zhanguo: The First Empire to the table a couple days later for two solo plays. The rulebook is great, but it would have taken me a little while to grasp some of the game’s original rules had it not been for the first play of ZhanGuo, particularly the game’s card mechanic.

Zhanguo, like ZhanGuo, is a hand management area control game for 1-4 players. Over the 30 turns of the game (which sounds like a lot, because it is), players have to manage all of the following things:

- Adding cards to their player boards, in each of the five regions that match the map, to increase their bonus actions when playing cards to the main board;

- Placing government officials in each of the map’s five regions, which helps quell the unrest in sections of the player board

- Hiring workers, by using generals to whip workers into shape and causing a small amount of unrest in the region where they are hired

- Building palaces, by using architect officials to direct workers and score in-game points

- Add Terracotta Army soldiers to the Mausoleum area of the board for both in-game milestone achievements and an end-game scoring mechanic

- Build walls to score end-game points and improve the actions of cards slotted in the player board

- Move a boat around the eastern seas of China, earning bonuses and slotting special cards into the player board

- Earn unification tokens to spend at the end of each round on one-time bonuses that align with the bullets above

Some players are going to see stars when they go through the teach for Zhanguo, and I was one of those players. On their own, all of these actions are fairly straightforward. For example, building a wall costs 1-3 workers, spent from various areas of the player board. And that’s it, because they don’t even score until the end of the game.

But the combination of these actions…oh my goodness, it’s a lot. Some people don’t believe in the weight rating on BGG, but I do, and a 3.8 out of 5.0 felt right to me. There’s a lot going on even for a gamer, and the weight of your decisions early on serve as a barometer of how well you will do late in the game.

And those actions are tied together with a card system that I absolutely love. This mechanic is the reason why I recommend trying Zhanguo, to see if the overall package is for you.

Higher, or Lower?

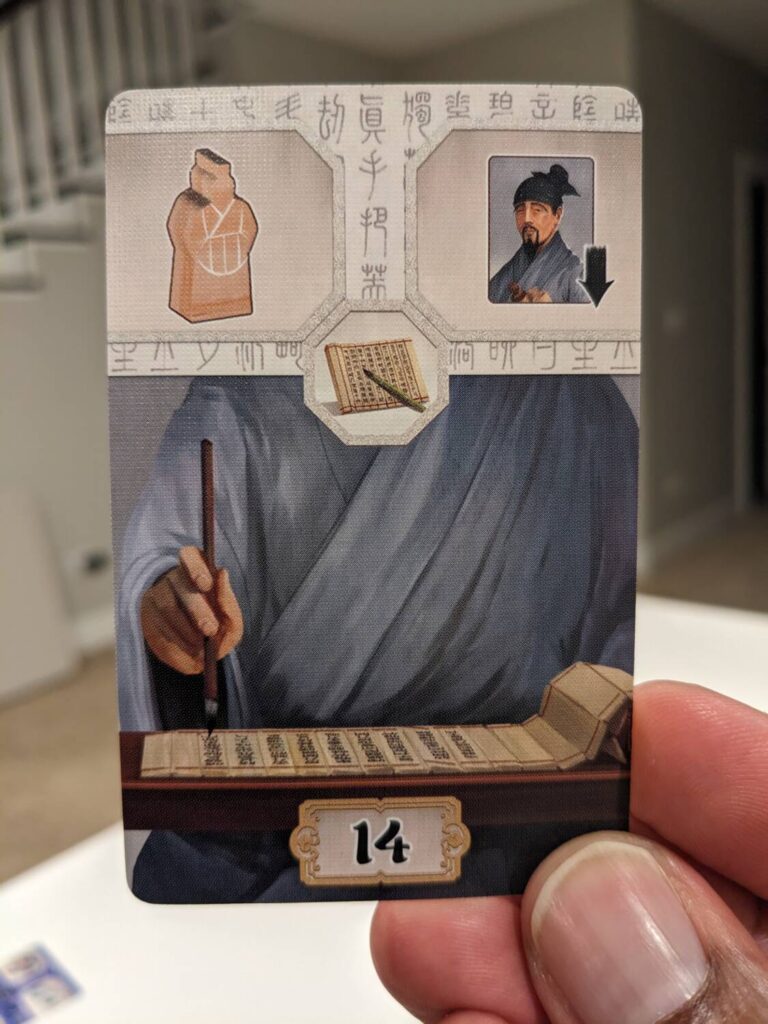

Each round, players are dealt six cards from the Unification deck, a 120-card set broken into three sections. Cards 1-40 are tied to Writing, 41-80 to Currency, and 81-120 to Laws. Each card has a unique number at the bottom of the front of the card, along with some fancy art, a Unification symbol, and an action that must be triggered in order to gain the bonus on the right side of the card.

Each card can be used in two ways. The card can be slotted under one of the five regions of a player’s tableau for its Unification action, which essentially makes every main action in the game a little juicier and also provides Unification tokens to each player. Playing a card in this way also grants the player a number of Unification tokens which can be spent at the end of the round.

The other way the cards are played: the Court action. In this way, any card can be played for any of the game’s six main actions:

- Recruit one official

- “Search for the Elixir” (yes, this is the name of an action)

- Install one governor

- Hire two workers

- Build a palace

- Build a wall

The Court Actions require a card to be placed on top of the previous card in the Emperor area. A player declares an action, and then they look to see what number their played card is versus the card they just covered up.

If a player wants to take one of the first three actions above (Recruit, Elixir, Governor), they have to play a card numbered lower than the card they just covered to trigger every bonus of every card showing the matching action in their tableau. The other three actions require a card higher than the covered number to trigger bonuses.

In this way, every turn features an interesting choice: what actions can I take that trigger the maximum number of advantages of my tableau, given the cards remaining in my hand?

In each of my Zhanguo plays, I love watching players curse when they see what the current face-up card is, versus what card or cards they have left in hand. I mean, I love it. None of the cards block any other card…it’s just a question of optimization. In my first four-player game of Zhanguo, I spent most of the final round cursing at no one in particular (but in a way, I was cursing the player just before me) as I tried to figure out how to use a card higher than the one played to build walls for end-game scoring, knowing that I didn’t want to play any of my 81-120 numbered cards for those actions.

It’s Complicated

I recommend Zhanguo: The First Empire, but the reasons why are a bit complicated.

Let’s start with the easy stuff. Zhanguo: The First Empire is a major upgrade—I would argue, complete replacement—over ZhanGuo, the original game. Every single thing about the new game is better than the original. The rules are clear. The artwork, by David Sitbon and Ulric Maes, is gorgeous; the box cover is a massive upgrade over the original game, the board is well designed, and I love the art on the cards.

There’s a significant boost in setup variability with the new game. All of the governor board bonus tiles, the Wall end-game bonuses, the Mausoleum milestone bonuses, even the Unification bonuses…all of it can be swapped and switched to your heart’s content. The board just has a really clean look now. The backs of the cards are bright and distinct; in the old game, all 120 cards had a black backing, with one of the three Unification symbols in the middle. Now, the Writing cards are bright white, with small symbols in columns on each card. The Laws cards are a beautiful shade of green; from across the table, it is exceptionally simple to determine what kinds of cards your opponents have left in their hands.

So if you were already a fan of ZhanGuo, I think Zhanguo: The First Empire replaces the need to own the original.

If you’ve never played ZhanGuo, my recommendation is a bit more complicated.

I love the cardplay, as noted above. I really enjoy the milestone system, which requires unlocked Terracotta soldiers to become eligible to score various milestones in the Mausoleum. That creates real tension when considering end-of-round rewards, and I liked that push/pull in each of my plays. I enjoyed the timing of installing governors and building palaces, driving the area majority scoring system as well as in-game scoring with the palaces. With the governors, I also liked managing the unrest in each region, and timing things so that I could clear that unrest with the governor action.

There’s a little too much going on across the entire game. I can’t figure out why I don’t like that, since I enjoy heavier games (using that same BGG weight scale, games like Trickerion: Legends of Illusion, City of the Big Shoulders, and On Mars all fit this description). I think it’s because I agree with the conclusion some players have landed on—the actions here are really simple to explain, and it’s also easy to explain the scoring system, but there are just a few too many things to juggle for some players.

A good example of this is the Search for the Elixir action. This mechanic adds two things to the Zhanguo enterprise. First, it adds a boat track, where players move a boat forward to a landing spot that provides bonuses along the way. Second, it provides a real purpose for the third type of official, the Alchemist. (In the original game, three different cube colors represent the officials, but they don’t really matter; the game just requires you to have all three cube types to flip them into a governor.)

The Alchemist allows for players to add cards into their tableau with upgraded bonus actions over the bonus actions from cards in the main 120-card deck. And there’s another condition—you can only add those cards in regions where you currently have an Alchemist in play.

This action is still meaningful, and can be used in interesting ways during play, but it feels like an add-on. You might go as far as saying that the Alchemists feel like expansion content in a different life. No matter what, players who have joined me at the table called out that the Elixir action, mixed with the half-dozen other ways to score points, makes for a game that feels like it is biting off a little more than it can chew.

As a result, Zhanguo is still a fun experience, but one that is not as elegant or streamlined as I was hoping for.

A few other negatives surfaced during play. The player aid tile is great at describing the six main actions. However, the iconography is the main challenge for players, even experienced ones; the backside of the tile could have been used to aid players with what all of those icons mean. (The chief icon offender: symbols that feature a down arrow versus those that do not. The down arrow is aligned with items/actions in the specific region of the card; no-arrow bonus actions can be done anywhere in your tableau.)

A lack of an icon guide meant that players had to regularly pass the large rulebook around…and the icon appendix is spread across the final FOUR PAGES of the rulebook.

Zhanguo can play 1-4 players. The solo mode is pretty good and it’s a great teacher for players new to the game, with automa cards that are fairly simple to manage. I would recommend sticking with 2-3 players, max; that will keep the entire affair under two hours. A four-player count is not recommended. I think players can still get the Zhanguo experience of tableau building and area control scoring along with that sweet cardplay mechanic with fewer players.

Plus, the downtime shrinks immensely, because during the game’s later rounds (when it feels like players take more Court actions, as opposed to slotting cards in their tableau), turns take a lot longer. Playing a card for its action, doing that action, then triggering 2-3 bonuses takes a couple minutes…and in a 30-turn game, that really adds up with a third or fourth player. (The main game board is double sided, with spaces aligned for 1-2 players on one side and 3-4 players on the other.)

At the end of the day, Zhanguo does a lot more right than wrong. I do recommend this to any lover of heavier Euro-style hand management games. I love a good multi-use card game. Zhanguo is a big piece of chicken, so the sense of accomplishment at the end of each game, win or lose, is something else. I wish it was a little more interactive, but there’s still plenty of interaction in the game—playing off of the cards in the Emperor area, fighting for area control, racing for milestones.

And, publisher Sorry We Are French crushed it on this production. Zhanguo is absolutely beautiful on the table; the table presence is fantastic. Much like their updated version of Iki last year, Zhanguo does justice to another game with an Asian theme with lots of great wooden pieces, distinct artwork and a snazzy rulebook.

Give Zhanguo: The First Empire a look if you think it will hit your group’s sweet spot; investing in multiple plays will yield great results for fans of heavyweight decision-making.

First, I love your reviews, Mr. Bell. Always a joy to read.

Second, I tried to put in a comment when I first saw and read this review; something was wrong and I could not. I contacted Mr. Matthews and he has corrected this — hooray!

Last, I wanted to say that I really enjoyed this review. This sounds like the sort of game I would love, but would need to get friends from hours away all into the same spot to play, because it is definitely not the sort of game I would be able to get my wife to play. 🙂

My friends are not nearly as far away as they once were — so there is hope!

Thanks! It’s definitely the kind of game that requires a group to do multiple plays, but I think that’s a good thing. The production here is really special.