(To learn more about Justin’s journey into the 18XX system, read his introduction here.)

About 18 months ago, I decided that I finally wanted to crack the nut when it comes to the 18XX system. It’s been a long and winding road, in part because the road looks like a path no one in my gaming group really wants to walk.

Recently, I decided to force the issue and get a couple of my gaming circles to play just one of these games to see what people think. After browsing the interwebs and building a short list that seems to serve an 18XX novice best—games like 1830, 18MS, Shikoku 1889 and 18Chesapeake—I decided to go with a choice designed by the person I trust the most: Tom Lehmann.

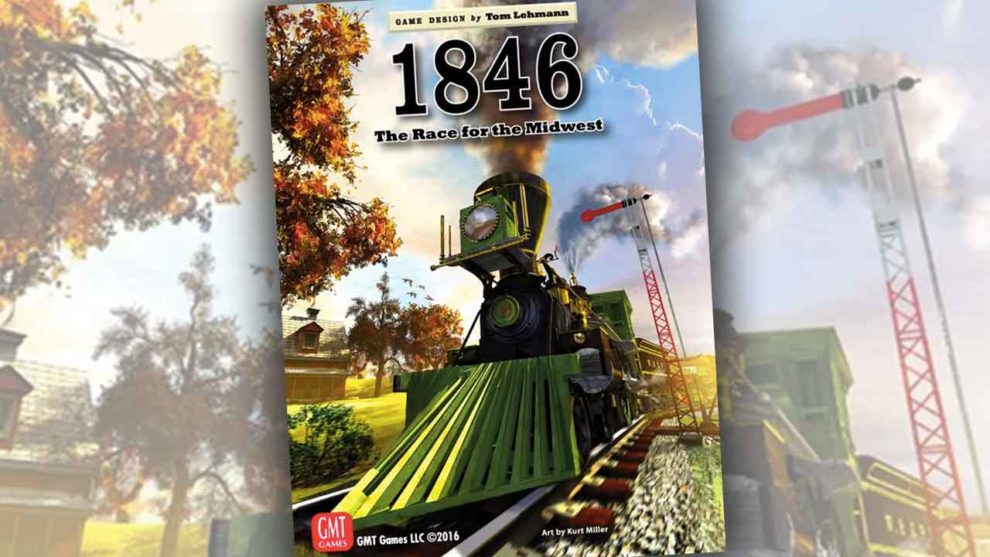

The man who has designed some of my favorite strategy games—Race for the Galaxy, Roll for the Galaxy, Res Arcana—also designed 1846: The Race for the Midwest (the first edition was released in 2005 by GMT Games). A second edition of 1846 arrived a couple years ago, so I dropped some cash to buy a second edition copy for myself.

I am thrilled to share that 1846 is not only a perfect game for strategy gamers who are new to the 18XX system, but 1846 is just a great game in its own right. I’m only five games in, but there are a number of viable strategies and lots of ways to have fun despite the game’s dry appearance.

18XX, with Guard Rails

I’d love to point readers to an overview of the 18XX system, but finding a short synopsis online was a major challenge. (My kids now refer to these games as “the boring train games Daddy plays”, so let’s just go with that for now.)

The 18XX game system was created almost 50 years ago by Francis Tresham with his 1974 release 1829. The critical response to 1829 was apparently lukewarm, so Tresham designed a sequel, 1830: Railways & Robber Barons. 1830 was called out most often by 18XX enthusiasts in my network and online as the best game to start my journey; “it’s a classic” was the line I heard quite often, and almost every 18XX game used the majority of elements in the 1830 ruleset.

1846 sparked my interest mainly because Lehmann designed it, but there were other things that sounded interesting while doing my research on the production. I’m based in Chicago, so any game that features the Midwest and/or Chicago with prominence is going to be on my try list. Like other 18XX games, there are trains that need to be built, corporations that need to be floated, and tracks on yellow, green, brown, and gray hexes to be built.

Many other things spoke to the 18XX rookie in me, such as the draft of private companies as opposed to an auction format. In many 18XX games, players start with a small amount of cash and then use that money to bid on small businesses. These businesses represent private business interests in the 1800s that were later consumed by larger railroad corporations for their specific regional or tax benefits of the time.

But, how am I supposed to know the real value of, well, anything, especially BEFORE A GAME EVEN BEGINS? How likely is it that I’m going to blow all of my cash on these private companies then find myself drowning when trying to invest in a new major train corporation?

This was one of the things that scared me away from the 18XX system: being blown off the table by a looming bankruptcy after spending four or five hours at a table. It seemed like 18XX fans were intentionally trying to scare me away with tales of trains “rusting” at inopportune times, being squeezed out of profitable routes by opponents, or running a corporation only to have that business snaked by another player who suddenly owns more shares.

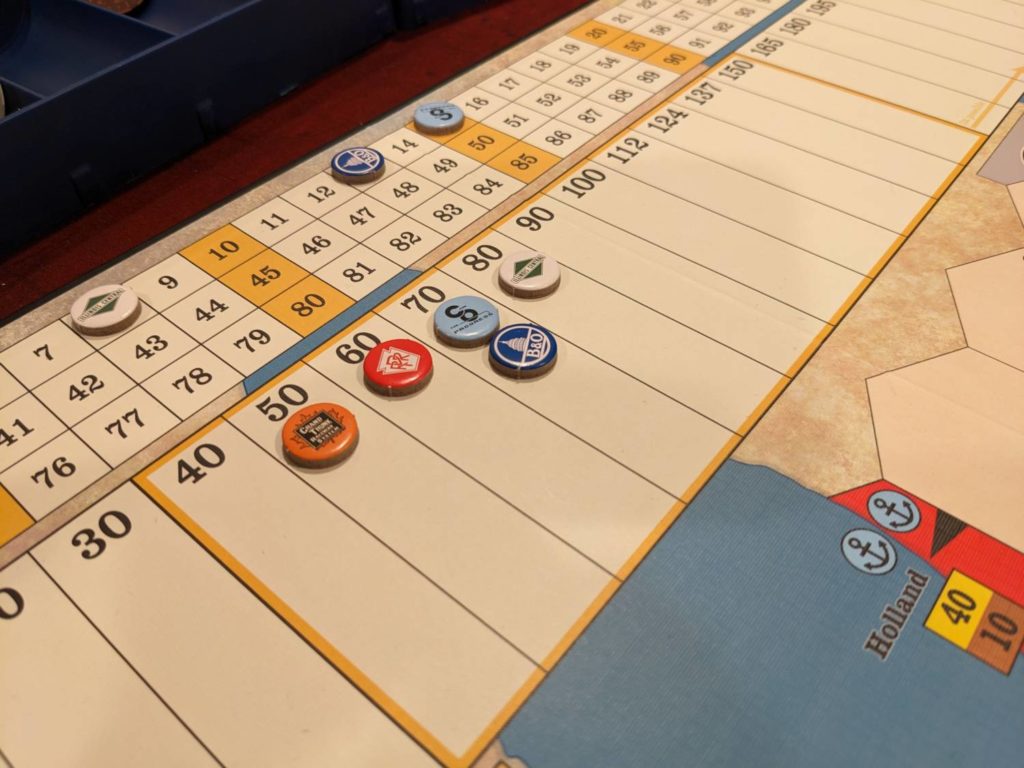

All 18XX games drive towards the same goal: the richest player wins. Playing a tycoon of some sort in a region new to the railroad business, players are tasked with “floating” one of a handful of historically accurate railroad companies with enough cash to make them operational. Running these companies as either its President or as an investor, players hope to earn dividends off of a successful series of route-running fulfillment activities.

There’s always a map of a region, with hexes available for corporation presidents to build track connecting major and (sometimes) minor city/town locations along with “off-board” locations, typically in red, around the outside of the map. 18XX games flow in a series of rounds, where stock rounds are interspersed with “operating rounds” when track is built and trains are run. Trains can be bought from the bank (or from other corporations), and each game’s passage of time is tied to the introduction of better, faster, larger, more expensive trains that can deliver imaginary goods and/or passengers to various destinations.

These routes are the basis of how all players make money in an 18XX game. The players who run the most profitable routes—and who invest in the corporations who run the best routes—typically win an 18XX game. There’s a lot of math, a ton of poker chips, and a lot of time spent sitting at the table.

Pop the Rails

1846 takes many of the standard features noted above, then streamlines them to make a game that is both approachable for novices and interesting for veterans. The goal of 1846 is to end play with the most money when players “break the bank” (empty the bank) of a pre-set amount of money scaled to the game’s player count.

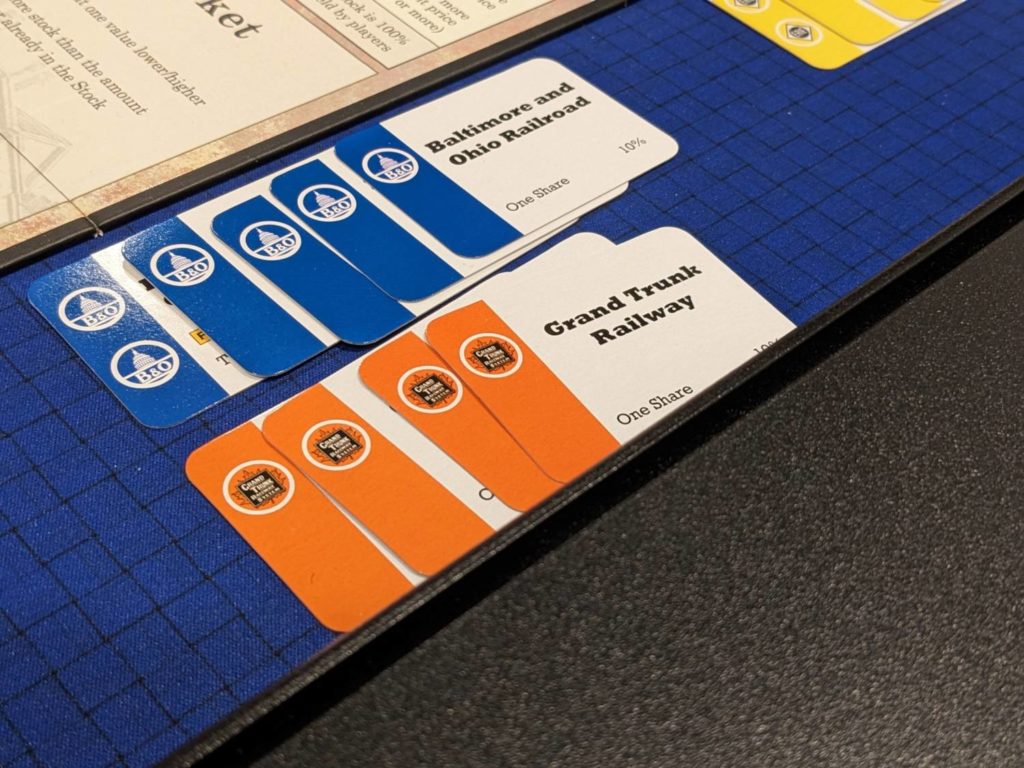

Play begins with a private company draft where players get the chance to take on private companies by selecting one card from a small hand. Each private company has a cost that will be paid after the draft is completed. Some private companies give the owner income every time an operating round occurs; some privates grant the owner special powers for certain hexes on the map. Two of the private companies are independent railroad companies, serving almost like baby railroad businesses, which operate like their bigger siblings but only pay out small amounts of revenue each turn.

Although I’m still new to 18XX games, one thing became apparent even during my first play of 1846: it has some nice, comfy guard rails to ensure that things don’t end in disaster right away.

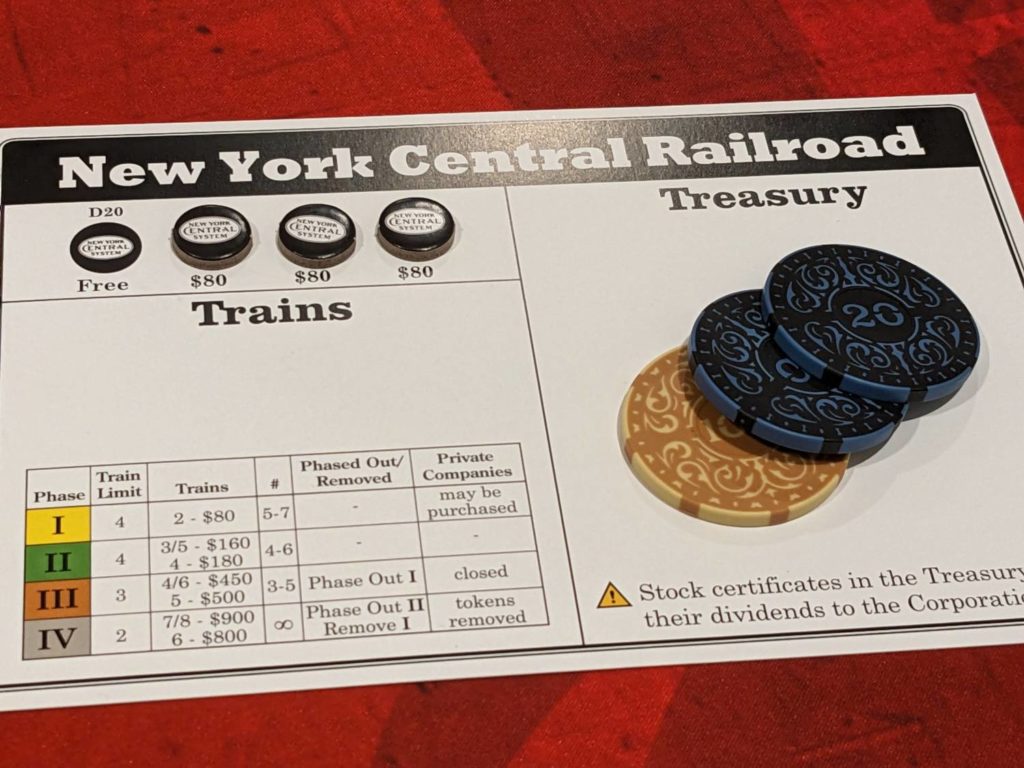

That starts with a pool of major train corporations that scales to the player count. 1846 can accommodate 3-5 players, and what’s nice is that in a three-player game, there are only five train companies that can be floated by the players. Most 18XX games have the same ruleset around starting a company: the new President has to set a “par” or starting stock price, then invest a portion of their personal funds equal to twice that starting stock price directly into the treasury of that new company.

An added bonus: in many 18XX games, companies don’t go into business until they have achieved “full capitalization” (typically 60% of a corporation’s IPO, or initial public offering based on its par price). In 1846, as soon as someone becomes the President and buys the 20% President’s stock certificate, bang—that railroad corporation is in business and begins operations immediately.

In stock rounds of other 18XX games, players can later sell shares of a corporation and potentially sink that corporation’s stock price; not so in 1846. Later, when operating rounds begin, laying track and running routes and buying trains all feel straightforward. The starting cost for all new tiles and upgrades is $20 per tile in most cases, and unlike many other 18XX games, players can lay two pieces of yellow (basic) track if they want, instead of just one.

If a President sees that they may need a little extra cash boost in that operating round, and it still has shares left in its treasury, they can issue shares at a price one level below its current stock price by selling some shares to the stock market.

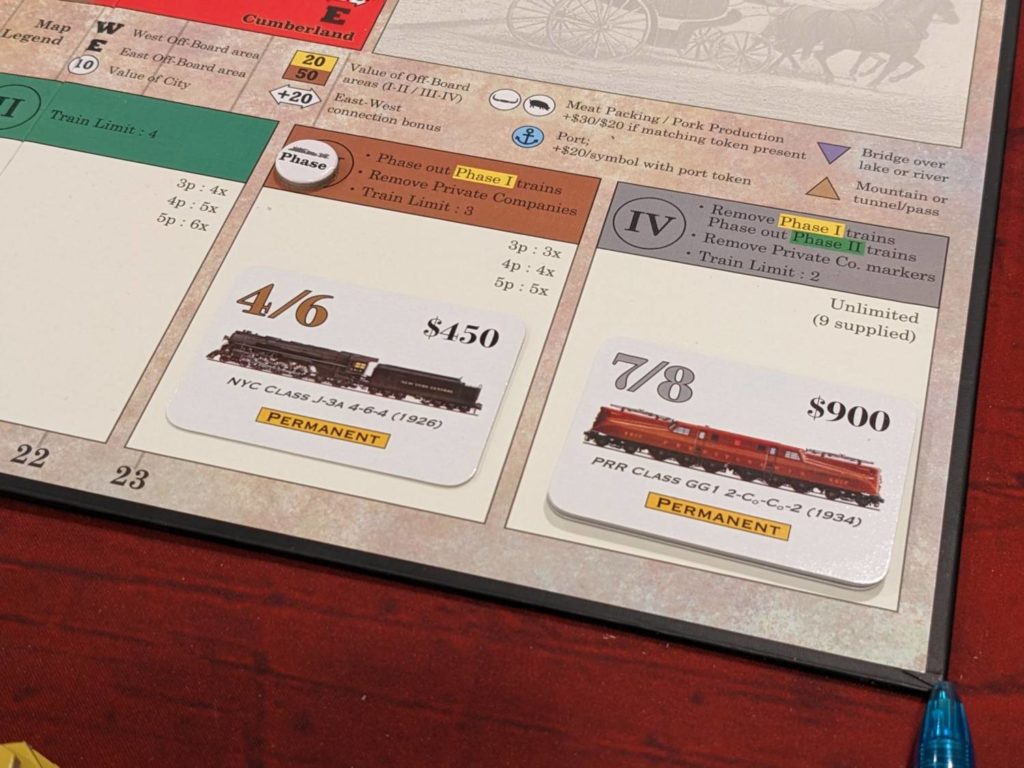

Even running routes and paying revenues in 1846 feels a bit more flexible than my understanding of other 18XX games. Like most 18XX games, trains in 1846 are labeled with a number—2, 4/6, 6—that call out the number of cities they will stop in to make money (and in the case of a 4/6, a train that will stop in four cities of a six-city route that allows it to pick and choose the cities that pay the most money).

Trains in 1846 don’t “rust” in the way they do in other 18XX games. Typically, when technology advances a game into a new phase, older trains immediately become obsolete. That process, simply labeled as “Phased Out” or “Removed” in 1846, feels like it takes longer here because you get one extra turn after a new phase begins to run with those old trains before they are lost to time.

After all of a corporation’s trains run their routes, revenue payouts can be made in full or half payments. A third choice allows for the corporation to withhold its earnings, which hurts the stock price but provides flexibility to buy trains in later operating rounds. This flexibility feels incredible when one needs to put more money into a company’s coffers before paying out big dividends, and typically doesn’t hurt the company’s stock price when half dividends are paid.

“I Won’t Lie—This Looks Pretty Boring”

Each time I was able to get 1846 to the table, the same commentary surfaced.

- “Man, this is even more bland than the pictures I saw online.”

- “This looks pretty boring.”

- “I know we are set on playing this, but I’ll be honest–this looks pretty boring.”

- “Uh, the train game? This looks pretty boring, Daddy.” (My daughter, after seeing the game fully set up on my gaming table.)

Then the games began…and the barriers to entry slowly began to drop. Everyone loves variable player powers, and the private company draft always provides fun moments to kick off play. (I adore how simple the private company draft is in 1846, right down to the moment when a final private company becomes available and players have to publicly decide to buy that final option at full price, or pass, giving the next player a chance to buy it at a $10 discount.)

It is interesting to see which corporation each player selects in the opening draft. That sets the stage for, in many cases, immediate competition from some of the factions that are based in the central eastern region of the board (B&O, New York Railroad, Erie). I can already see synergies between running Grand Trunk—based in the northeastern section of the 1846 map—and running Michigan Southern, one of the two independent rail companies that can be drafted during the private company draft to begin play. And everyone loves the small bonuses that the Mail Contract provides; this private company persists throughout the entire game, even after other private companies are forced to close.

Players looked more and more engaged with each round. The decision space in 1846, and by extension, 18XX games, tickles a nice sweet spot for me. I love economic games. I enjoy really interactive games. The threat of bankruptcy provides a nice tension without feeling like a foot constantly stomping my chest. The puzzle of trying to find a piece of track that upgrades to my needs is always interesting, and is getting easier as I stare at these options across multiple plays.

But even after only four games of 1846 (two at four players, two at three players), I’m surprised at the variety of things I found to succeed and to fail. I have tried to mix up which corporations and privates I use in each play; seeing how each of them work is one thing, but trying to make them fit with both a short-term and a long-term strategy has been really interesting. Being forced to pivot is something I have greatly enjoyed; when I’ve been cut off with routes, or when another player’s business failures have changed the dynamics of play, or when the inevitable “train rush” happens and I am both ready and sometimes not ready for it…man, it is one thing to be ready for change, and a totally different thing to successfully adapt.

I’ve already been a part of great moments, stories that we are recounting in text and PM chains hours and days after games have wrapped. It wouldn’t shock me if there are people out there who play 1846 on a monthly basis, and have seen games play out in slightly different ways every time. Play time also drops with successive plays; I could see five experienced players finishing a game of 1846 in under three hours, less with a smaller player count.

A Solid Kickoff

As an introduction to the 18XX genre, 1846 answered my prayers: be interesting, be easy to learn, be difficult to master, and provide a glimpse into the realm of possibility with this gaming system.

I will note that the main downside of 1846 is that it differs from almost every other 18XX game that I have played.

For example, most of the ones I have tried feature full capitalization (granting a corporation 100% of its funding after it has been floated at 60% of its total), whereas 1846 does this differently. Stock shenanigans are prevalent in almost every other game, but in 1846 opponents have a much harder time denting market value.

Phasing out trains in 1846? I love it, but I haven’t seen that in any of the six other 18XX games I have seen so far. (18MS is the only one that even compensates players for trains that have rusted out of play.) The private draft is unique. I also haven’t played another game yet that has N/M trains that let owners cherry pick the most profitable routes.

All of this means that while I still love 1846, it is fair to level the criticism that 1846 may not be the best preparation for what else is out there on the 18XX front. I actually love 1846 more as an 18XX adjacent experience—still a nuts-and-bolts 18XX game, but a better fit for my game groups than some of the others I’ve tried.

In terms of production, the second edition of 1846 is very nice. Save for the paper money—which looks fine, but I’ll never use it since I only use poker chips as currency—everything here is handsome without being deluxe. The cardboard tokens do the job; the hex tiles are easy to read and call out the special symbols needed to quickly make decisions. My other GMT gaming experiences line up well with 1846, in terms of quality; everything in the rulebook is laid out well and easy to find.

A special shout out to the example rounds of play that are detailed in the back of this rulebook; that made any questions we had evaporate after reading that section.

If you were like me, and hesitant to jump into 18XX games, I highly recommend giving 1846 a look. I also plan to use 1846 any time I have new 18XX players interested in trying out one of these games since it feels like this is a friendlier way to show rookies the ropes than peers such as 1830. It’s a major time investment on the front end, but it’s an investment that I’m happy I made!

Add Comment