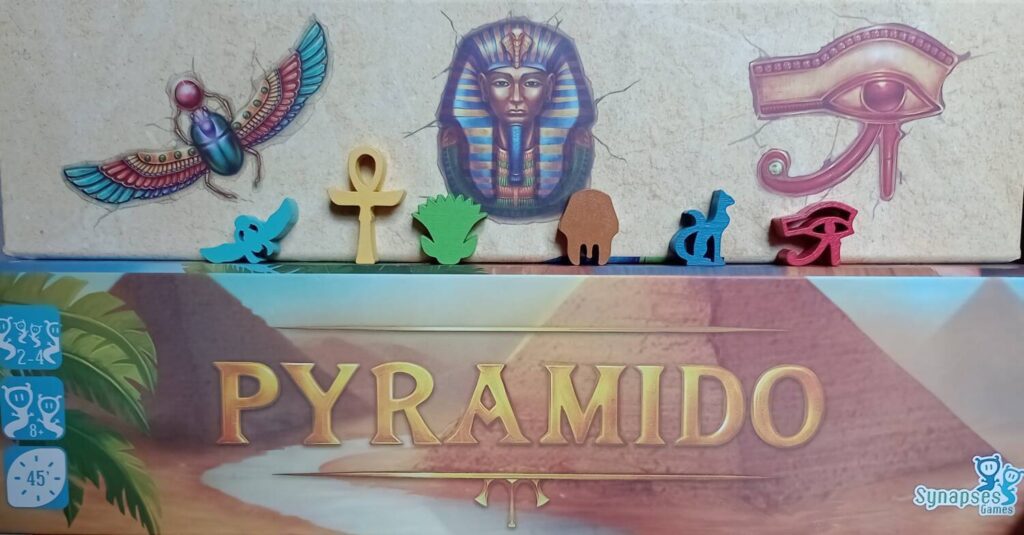

Pyramido is a handsome game. Colourful tiles, playful icons, bold wooden markers, a vertical build, the tempting façade of tabletop satisfaction. It’s a charming way to spend half an hour or so.

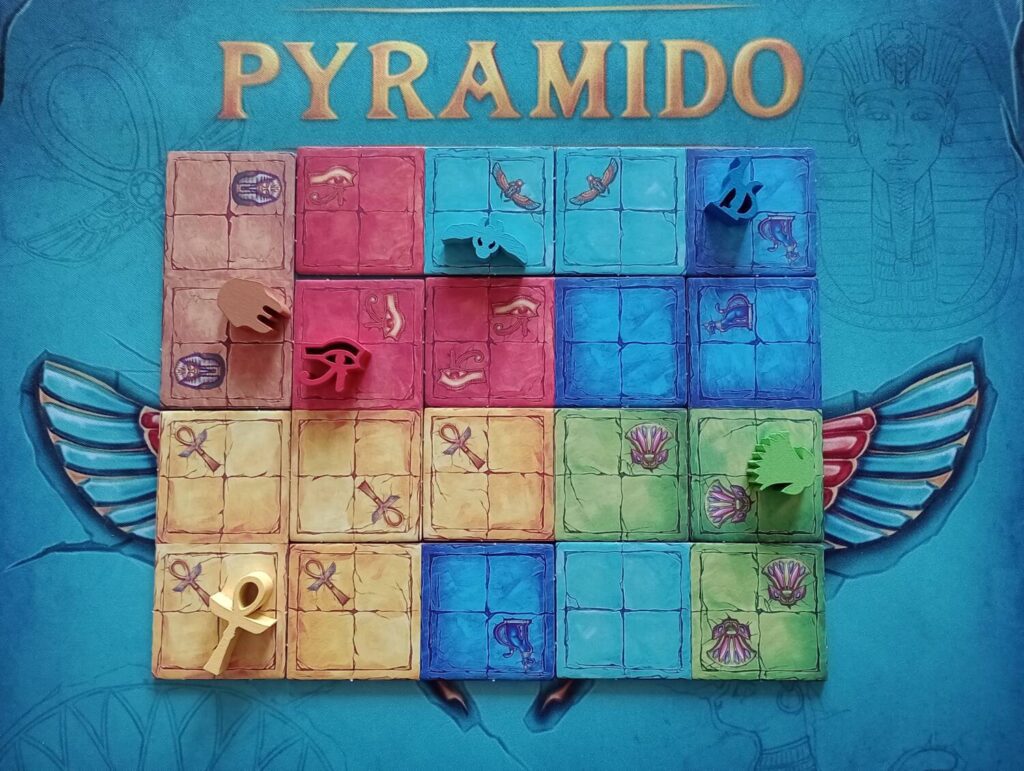

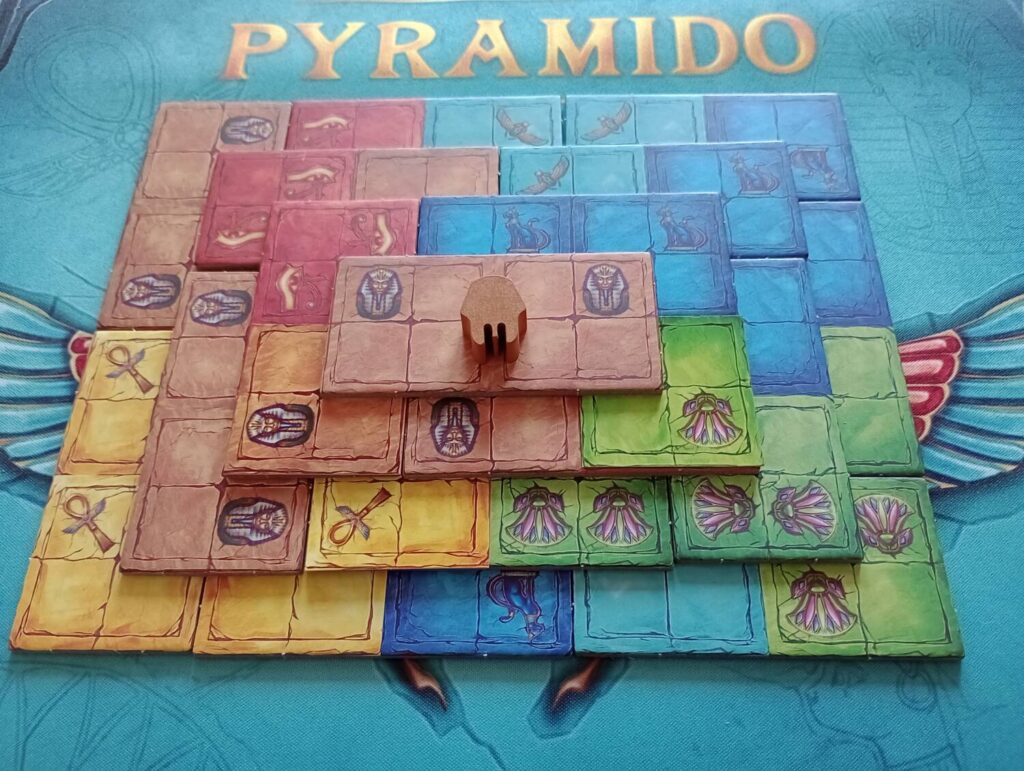

It’s also simple to play; a pyramid complex this is not. On your turn you’ll take a domino tile, placing it into your personal pyramid and sometimes placing one of those cute wooden markers on top. There are four rounds to the game and during each you’ll build another layer of your pyramid, starting with 10 dominoes (creating a 5×4 grid of half-domino squares) and in the final round capping your pyramid with a single domino.

At the end of each round you score your 5×4 grid from above. Some dominos have icons on one or both halves and you’re trying to create areas with lots of icons in each of the six colours. However, you can only score an area if you’ve placed a scoring marker in it during the round. Points are awarded for the number of icons in each marked area, with a bonus for your lowest scoring area.

Tot up the scores, remove the wooden markers and then go again, building a fractionally smaller rectangle directly on top of your previous one, the coloured zones bleeding across layers. Repeat until you’ve played the fourth round and Bob’s your uncle.

I’ve streamlined, of course. There are some minor rules about how you place your wooden markers and you start with three double-sided resurfacing cards that allow you to swap the colour of any half-domino, but really that’s about it. It’s straightforward, with just enough decision points and constriction to keep it interesting.

Look Beneath the (re)Surface

You’ll want to play these resurfacing cards at just the right moments. Since the final round only involves taking a single domino, you’ll probably choose to hang onto one to give yourself options in case the limited tile market doesn’t have options that align with the colours you’ve majored in. And you’ll probably major in two or three colours – it’s difficult to maintain high scoring for all six colours beyond the first round.

How tiles are placed in the market is also interesting. There are three faceup tiles available in the market to choose from. Take one of the three tiles in the market and then choose which of the two faceup reserves will take its place in the market. It’s clever: you can clearly see what’s available on your turn and influence what’s available for the next player on their turn. You want to maximise your own points, potentially even seeding the market with a domino you’d like on your next turn, but perhaps it’s best to deny your opponent a scoring opportunity instead.

These subtle decisions run through Pyramido. I’ll say here and now that Pyramido doesn’t do anything startlingly new or original (and we’ll discuss one particular tabletop ancestor later) but designer Ikhwan Kwon has crafted a game that’s quietly clever, understated despite the bright colours and layers.

When you’ve arranged your tiles just right and get to place that final tile (and ideally a resurfacing card) to score big it’s a deeply satisfying game. Publisher Synapses Games have a great track record and once again they’ve done a great job. The tiles are thicker than your average tile-laying game, although it would have been nice if they were even thicker to heighten your build further. The final pyramids look great but a little like someone’s sat on them. A minor flattening of an otherwise impeccable production.

The Little Onion

Like the tiles themselves, the gameplay is good but not especially deep. There are a couple of things you learn to do in your first game that you should do if you want to score well, after which it’s the same approach every time. These are so fundamental to success that to play with someone new without giving them that crucial advice would be unethical.

And then there’s the pharaoh in the room. Much of what Pyramido offers has been done already by another simple game with colourful dominoes, an interactive market and icon-based scoring. Pyramido provides a different experience but it’s hard not to make the comparison. Without a doubt Kingdomino is the better game. It’s sharper, cleaner and the tile selection process is the best in the hobby.

What sets Pyramido apart is its fascinating arc. The decreasing number of turns each round contrasts with the importance of those turns. Across the final two rounds (which might produce half your points or more) you only take 4 turns total. The final round is just one turn and yet a quarter of your points might result from that single tile. In some ways, unlike with almost every other game out there, you become less powerful and influential as the game goes on. Sure, you can mitigate as much as possible, but in reality you’re building your pyramid whilst eroding your own scoring options.

Except that as what you can do for yourself withers, what you can do to others grows, two melodies harmonising. The mechanics behind the tile market become more important as the game goes on. Simultaneously, the game state across the whole table becomes easier to read. You gain a greater appreciation of what your opponents want and, as a result, can have more input into what they can actually get. The opening round or two are so open, so easy-going, but after that things can get a little mean. Going first in the final round can be remarkably powerful, denying an opponent anything useful on their turn could completely ruin their chances of success.

Phar(aoh) Play

It’s that market-based pettiness where Pyramido falls short of Kingdomino for me. Let me explain. In Kingdomino, tile choice is based on three factors: what you can score, what your opponents might score and where you want to be in turn order in the next round. These vie for your attention, jostling with each other to influence your decision. When you deliberately take a tile that you know an opponent wants, it’s a decision weighed up against how it’ll impact your own score and where you want to be in turn order. It’s meaningful, with the potential for sacrifice.

When you’re taking a tile from the market in Pyramido, some of these elements hold true to a lesser extent. But when you come to selecting the next tile for the market, screwing your neighbour over feels undeserved. Sure, it’s the right decision in terms of trying to win the game but it’s an easy decision and there’s no consequence to you. It’s unearned. Don’t get me wrong, I love games where you can make things awkward for your opponents, but the best of them involve a cost or compromise. You’re hurting your opponents instead of helping yourself, or you’ve previously worked hard to be able to help yourself and hurt others at the same time. That’s completely absent with Pyramido and it’s a weaker game for it. With barely any effort, you can ruin someone’s whole game.

Sometimes you don’t even have to try to hurt them. There are a lot of tiles and it’s not uncommon, by random chance alone, to find yourself entering the final round with nothing remotely useful in the market whilst someone else has one or two great options. When the tiles aren’t showing anything useful in the market or its feeder, and that’s not down to your opponents, it’s a little disheartening, even if you do have a resurfacing card to hand.

Happy Cappers

Happily, Pyramido is short enough and pleasant enough that the occasional luck-based blip is forgivable. And whilst I’ve been critical in the last few paragraphs, these are relatively small issues with an otherwise great experience.

With Akropolis and others it feels like tile-overlaying is having a mini-moment and it’s great to see Pyramido taking the approach with dominos. It’s not quite perfect, but it’s a cracking looking game, satisfying and enjoyable.

I enjoyed your review — very good stuff. I think this is game I will pass on, however. Nothing remotely interesting or different enough to pull our attention away from the games we already play.

Thanks for sharing!