One of the many advantages of getting intellectual property for your board game is leveraging the audience to look at your project. For example, developing games based on well-known franchises like Marvel or Game of Thrones allows you to tap into those brands’ existing fanbases. Fans of the IP are likely to take an interest in a related game, even if just to check it out briefly via marketing materials or initial coverage.

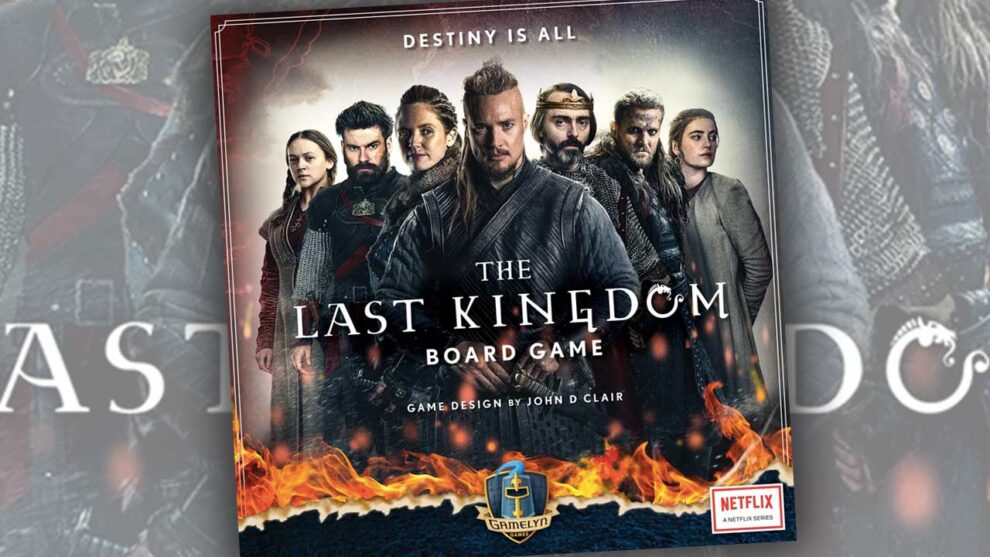

Which leads to my confusion about today’s game, The Last Kingdom. Based on an obscure Netflix show, it only made a blip on my radar due to some YouTube hype around it, calling it a “hidden gem” or “game of the year.” After checking them out and realizing that this is an area control drafting game where you can switch allegiances, I had to see this one to the end.

The Last Kingdom throws you a position of power of the political kind. You are a figure of importance during a time when the Saxons and Danes are having a series of cultural exchanges on the battlefield. Like any other board game, your power in this world is measured through victory points.

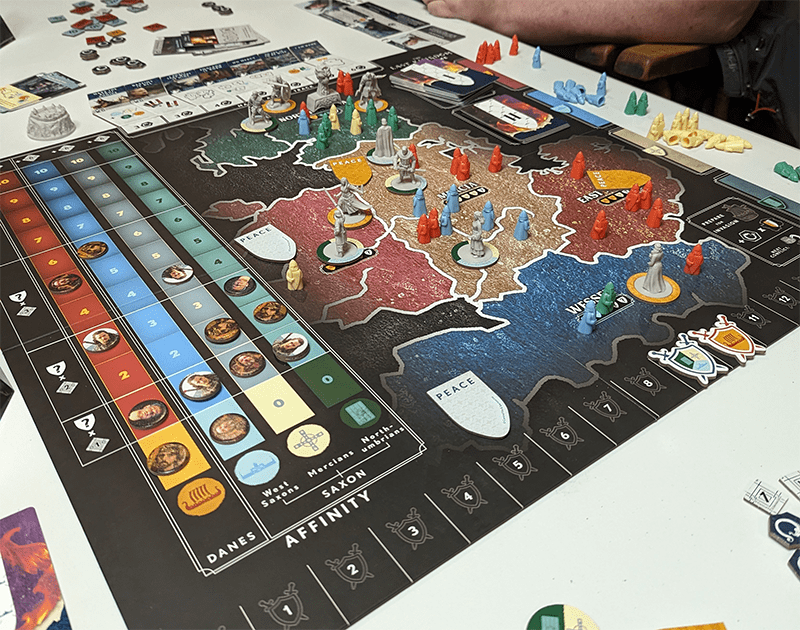

Based on that description, one can easily assume that this is a Risk-style or “dudes on a map” board game, and they would be somewhat right. Most of the army pieces on the board are fighting with each other, but none of them are owned by a single player. You are a leader allying themselves with either the Saxons or the Danes, and it’s only through their conflict victories that you score points.

United We Stand, Divided We Score Points

Except it isn’t that simple. Besides having their own abilities, each leader also has starting affinities with these factions. King Alfred is obviously going to do well with the Saxon factions, especially the West Saxons, over a recently converted Guthrum who has a history of decorating the landscape with Saxon blood. It is quite possible for the vast majority of the table to be allied to one faction to score points, but someone in that small collective is gaining more points than everyone else for each conflict victory due to their affinity, and that person is probably not you.

That may seem complex already, but there’s even more to unpack with The Last Kingdom‘s gameplay. Each of the two rounds begins with a standard card draft, where you select one card from your hand to keep before passing the rest to the next player. After the card draft, players take turns resolving conflicts across the five provinces on the board, one province at a time.

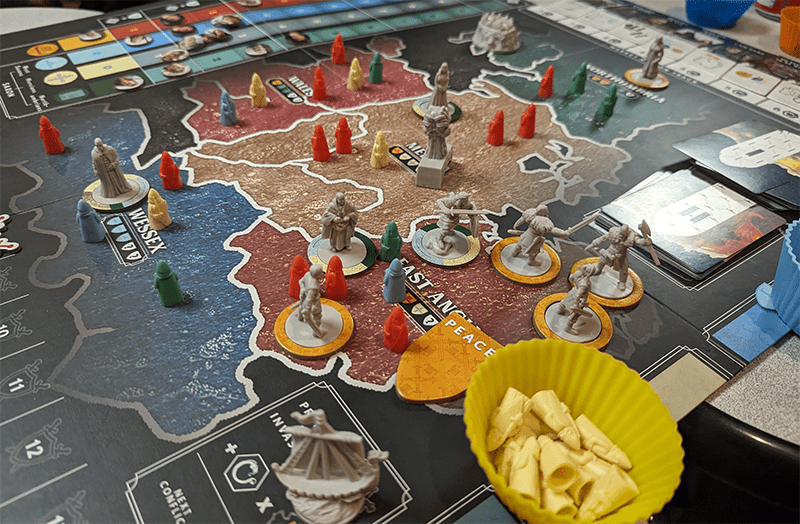

The drafted cards provide a variety of actions for each round. Your options include increasing your affinity with certain factions, gaining action tokens, unlocking new permanent abilities, moving or placing new armies, and bringing hero figures with special powers onto the board. An interesting asymmetric element is that each player’s draft hand contains two cards specific to their chosen leader, further differentiating your options and abilities from other players. The card drafting in The Last Kingdom not only gives you several tactical choices, but also deepens the existing asymmetry between leaders through these unique cards in your hand each round.

My Kingdom For A Card

What makes the card draft even more engaging is that the six cards you choose end up being your only cards for the entire round. You need to make it through five province conflicts using just that starting hand of six cards. This limited card supply creates tense decisions. If you don’t want to play a drafted card, you can instead spend action tokens to take one of the generic Market actions available on the board, such as moving armies, placing new ones, or switching allegiances. These Market actions serve as supplementary options you can leverage when you don’t want to use a card. Having this flexibility with the Market alongside your six-card hand gives you some strategic wiggle room when plotting your approach across the round’s many conflicts.

As for resolving conflicts, it’s not that hard. On your turn, you can take as many “Secondary” actions as you want, like certain playing cards or using specific Market tiles. Then you must take one “Primary” action – either playing a card, using a Market tile, passing, or preparing for invasion. Passing skips your action for the current conflict but allows you to play again when it goes back to you. Preparing for invasion is like a “super pass” – you exit the conflict for good but gain action tokens, and you get to select the location of the next conflict.

Conflict is resolved when everyone passes in sequence. The side with the most strength – determined by the number of figures – wins the conflict in that province. Players allied with the winning faction gain points, while those on the losing side receive action tokens as a consolation. There are additional bonuses for being the sole winner or sole loser in a conflict – such as extra points or action tokens. As a side note, your action tokens and victory points are hidden behind your player screen from everyone else.

There are those who call me…

To put it briefly, The Last Kingdom feels like a “greatest hits” compilation of the best elements of area control games from the past decade. It amalgamates and celebrates key mechanics and designs that have made area control such a popular genre recently. I see DNA from several standout titles, like the drafting of Blood Rage, the army factions of King is Dead, the timing of card play and passing of Inis, the scheming of War of Whispers, and the limited hand management of Condottiere.

As someone who has played quite a few area control games, with one of my earlier reviews being a praise of Inis, I can say with the utmost confidence that The Last Kingdom is my favorite in the area control genre. If I had played this before the end of 2023, this would’ve been my personal game of the year. The only way this game is leaving my collection is if it sets itself on fire or if I overplayed it.

That’s a bit of praise, but where is it coming from? I’ll start with the one that grabbed my attention the most: Allegiances.

The core conflict in The Last Kingdom pits the Danes against the Saxons. Though you begin the game allied with one side, you can switch allegiances over the course of play through certain cards or a Market action. Sticking with a single faction for the entire game is rare, as neither side can dominate every conflict.

You need flexibility to align yourself with whoever is winning in order to score the most points from those victories. This dynamic echoes historical rivalries, where allegiance between factions shifted constantly based on who held power. Loyalty is a fool’s game here and like modern day living, moving up in life requires you to be friends with the right people. With such a grand idea embedded in the game’s themes, it does sprout concerns such as uneven alliances, like a three versus one scenario, right?

Et Tu, My Ally?

The shifting allegiances are kept in check by each player’s affinity levels with the factions. You gain more points for a faction’s victory if your affinity with them is higher. So in a three-player alliance, one player might score 16 points for a win, another 12, and the third 8 based on their respective affinity levels. These scoring differences incentivize betrayal and self-interest even among ostensible allies. If you help a faction win but reap fewer rewards due to your low affinity, you’ll eventually pivot to boosting your own gains rather than aiding others. Because of this, it makes betrayal feel inevitable instead of hurtful or forced like in many other games of this type.

This affinity system also emulates the fragile nature of allegiances – you may cooperate for a time, but your ultimate concern is your own leader’s supremacy. To make this even more complicated, the Saxon allegiance is divided into three separate factions, while the Danes are just one, so winning with them requires not only having a higher strength but also having the right colors that benefit you. Sometimes, doing this might involve some sabotage.

All of this sounds quite daunting, especially for someone stepping into the game’s shoes for the first time, yet it doesn’t present itself that way. The strengths of each faction in a conflict, all players’ affinity levels, and army placements are open knowledge. There is no unpredictable randomness from dice or out-of-turn card plays. You can easily assess the state of the board and a quick glance at your cards highlights all of your available options.

Ruling a Transparent Kingdom

The only information you don’t have is the other player’s action tokens, their victory points, and the cards in their hand. This creates a fertile ground for the player’s personalities and interpretations of the situation to constantly clash with each other throughout the entire game session. Players might over-invest in unworthy conflicts, move armies away to gain an advantage in future conflicts, or build affinities with dominant factions. You are perpetually dancing on a knife’s edge between making the stupidest of decisions and scheming the greatest of plans. Comfort does not exist here; there is only everlasting unease and endless opportunities to mess with your opponents.

Unfortunately, this feeling of unease continues with the rulebook. In certain areas, it gets bogged down in overly detailed minutiae, while in other spots, it glosses over key information. The result is a sense of confusion and omission reminiscent of an M.C. Escher artwork. The player aid doesn’t provide enough clarity on some mechanics and the game terminology could’ve been clearer. Overall, the rules aren’t a deal-breaker, but issues persist that create an onboarding issue.

The bigger issue is the leader powers. No, this isn’t a complaint about balance. However, I don’t need to be a top tier competitive player in The Last Kingdom to point out that a lot of these powers whip you into playing a particular style.

I Didn’t Vote For Him

For example, King Alfred’s abilities initially seem intriguing. His main gimmick is that he can never ally with the Danes. Instead, he gains points whenever an effect increases his Danish affinity or switches allegiances. In regions with Alfred, other leaders cannot switch to Danish either. Plus, Alfred begins with extra action tokens to frequently use Market actions.

On paper, this sounds dynamically asymmetrical. But in practice, you end up simply going through the motions of Alfred’s abilities each time rather than deeply engaging with them. His powers are so prescribed that you feel like you’re playing with a script instead of creatively harnessing them.

Not all powers are this heavily focused, but it is clear that you are meant to play in a particular way with each leader. The only challenge is the road to that destination, as you have to deal with the ambitions and decisions of other players to reach the apex of your leader.

Also, this is more of a warning but The Last Kingdom can be quite unforgiving. This is a competitive game in a classic sense, meaning modern concepts like “catch up mechanisms” aren’t as prevalent as some might think. You get some consolidation for losing conflicts, but you will find out quickly that this doesn’t supplant poor decisions. The Last Kingdom slaps you hard for making dumb plays and makes sure you feel that sting. I would be lying if I said every person who played this game with me walked away with positive impressions.

For those who don’t mind cutthroat area control games, The Last Kingdom offers an appealing compilation of proven mechanisms and high interaction. The interplay of card drafting, shifting alliances, and open province conflicts creates an engaging intellectual experience that few games provide. While the rulebook could use refinement and some asymmetric powers feel routine after the novelty wears off, the core gameplay loops deliver ongoing tense decisions from the start to finish. The Last Kingdom is a celebration of everything great about area control games, but sadly, it isn’t getting the attention it rightly deserves.

Add Comment