Jinja is a nice little worker placement game from Wizkids about constructing Shinto shrines across a mythical medieval Japan. The artwork is pretty, the board starts bare and eventually grows into a sea of different coloured shrines, and there is enough mechanical depth to make Jinja enjoyable on repeat plays. But is that enough to stand out in the crowded world of Worker Placement games?

Jinja sees players placing workers across Japan and on specific work tiles to gather resources in order to build shrines. Shrine construction is based on specific locations and a specific assortment of resources. Players need to be quick though, as there are very few open spaces in each region to accommodate new shrines, and particularly in large games the competition for resources, space on the worker tracks, and space on the board, will quickly become the core drive of the game. More often than not, turns will become exercises in minimizing damage and planning for the future.

Achieving Victory in Jinja

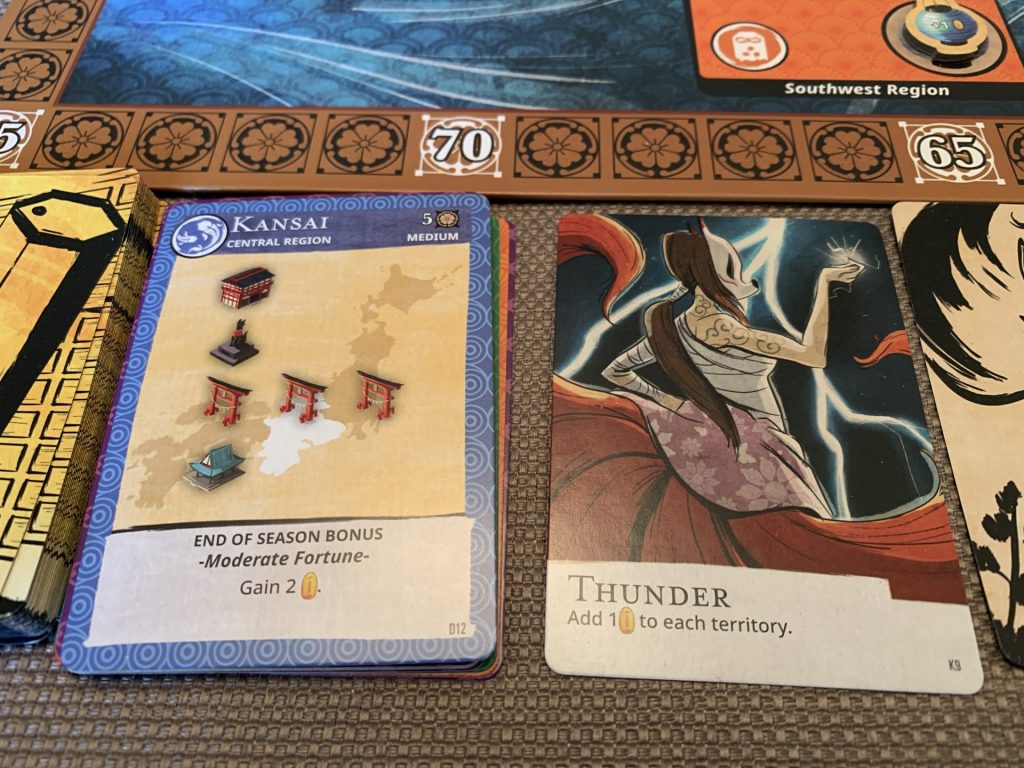

At the start of the game, players draw a random hand of victory conditions. These can range in difficulty and value from owning a certain size shrine in a certain area, to owning multiple shrines across multiple areas or owning the most of a certain size of shrine. After that, players draw a hand of potential shrines. Each one is specifically situated in a certain region and requires certain resources to produce. These cards are drafted amongst players, with each player picking a card before passing their hand to the left. Eventually everyone will have a full hand of shrines. Knowing what victory cards you have makes this part easier, but also becomes a game within a game.

There are only five turns, each one given a special rule thanks to the kitsune spirits. These range from extra victory points when building shrines, to opportunities to change some aspects of the board, but all serve to throw wrenches into some plans and grant unexpected windfalls to others. Most of the time, however, the change is a minor one that serves to add a little flavour to each round and keep players on their toes.

Shrines need building, resources need acquiring

Players proceed in turn order attempting to place their workers in the best spots to achieve their goals. Aside from the map locations, each with one spot, there are global collection spaces that offer money, resources, victory points, or new shrine cards. Placing a worker in a region on the map allows players to either gather the resources that sit on that region and are added at the start of each round, or else perform shrine construction. This means that there is only one map space, and one space on the global worker track, that directly allows the building of shrines in a particular region. Even resource gathering is strictly limited by the spaces available. Similarly, there are only a few places on the worker track to place workers to allow for building, so time is tight and space is limited.

The fact that resource acquisition is mostly random couples with the difficulties that come from a crowded board. A lot of the time Jinja felt like an exercise in luck mitigation. In one game, a player was exasperated that the ‘pay 2 coins for a resource of your choice’ space was taken each time before her first action. By the time it came to her turn as first player, she had amassed quite the pile of wealth and apparently useless resources. Of course she attempted to mitigate this by using some of the other tiles, but it can be very difficult to achieve the results desired. On the other hand, a game lasts only five rounds, and finishing an entire game of Jinja won’t take very long. So players aren’t subject to misfortune for an overly long time.

A Note on Theme

I’m a little torn when it comes to Jinja’s theme. There are a lot of innocuous appeals to pop images of medieval Japan, but others that seem a little bizarre. Thematically, the creation of Shinto shrines in the middle ages was part of the build up of regional power centers and the game reflects that to a degree. The odd inclusion for me personally was Hokkaido, which offers five building spaces for shrines, the most in the game. Hokkaido, for most of Japan’s history, was a periphery occupied majorly by non-Japanese peoples. It wouldn’t be until the 19th century that extensive colonization by Japan occurred. While I am not a scholar of Japan’s Middle Ages, I am aware of some contemporary settlement along the southern peninsula around modern Hakodate, but it seems odd to me to include all of Hokkaido given the timeframe. Rather than being a statement about Japan’s cultural and societal penetration of the region, it feels like a modern map of Japan was consulted, Hokkaido included, and little further thought offered.

Other thematic elements feel strange. Like the core mechanic of acquiring mostly random elements of a Shinto shrine works as a game, but how could I mistakenly commission 5 Torii Gate resource tokens but be unable to build because my proposed shrine lacks a Honden (A very important part!). I’m also not super impressed with the use of ‘honour’ as the victory point tracking method. To most I suppose these things won’t matter, but I felt it important to include.

Conclusion

I like Jinja, mostly. I think it does a good job of creating a stressful environment where players need to actively seek to better their situation with very few resources. I appreciate how the board turns from empty to filled with brightly coloured shrines. I like the flow of the game and how quickly a game can be resolved. I’m less sold on the theme as a whole. Little things make me think that the religious and cultural connections between the game and what the game represents were taken lightly, and because ‘Japan’ as a theme sells. It will probably stick around on my shelf because of its ease of play, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the randomness or the theme pushes some away.

Add Comment