Some say Ludwig II of Bavaria was a dreamer, devoted to extravagant expressions of art. Others say he was one meeple short of a completed component list, earning him the title of “Mad King.” History tells us he spent much of his personal fortune building extravagant castles such as Schloss Neuschwanstein.

Between Two Castles of Mad King Ludwig (also considered by many to be the most extravagantly-named game in Board Game history) was designed by Ben Rosset and Matthew O’Malley, the same team behind the Stonemaier Games publication Between Two Cities. Between Two Castles is a unique mashup of two previously-existing titles; Between Two Cities and Castles of Mad King Ludwig. Stonemaier partnered with Bezier Games to combine the gameplay mechanics of Between Two Cities with the room scoring triggers of Castles of Mad King Ludwig to build this new game. But does the combination of these two games create something greater than their foundation?

Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

In Between Two Castles of Mad King Ludwig (every time I type that name, I eat up my word count) you play as a master builder commissioned to work on one of King Ludwig’s castles. You must work with the other builders to complete the castles, but only one builder will become the most renowned.

If you’ve played Between Two Cities the overall mechanics will seem very similar. This is a tile-drafting game where players are selecting room tiles to “build” into castles. The rub is that every player has two castles they need to build; one on their left which is shared with an opponent, and one on their right which is shared with a different opponent. Players are literally sitting between two castles. (Consequently, my toddlers would hate this game because they don’t know how to share anything.) At the end of the game, the castles will be scored, but the lowest scoring castle for each player will be their final score. This forces players to work with players to their left and right to create a high scoring castle but keep it balanced with their other castle. If one castle is left underdeveloped, it will become the final score for at least one of the players who constructed it.

Players will start the game with a hand of nine room tiles. They will simultaneously select two tiles they wish to play and set them aside face down. Once all players have chosen their two tiles, they reveal them and place one tile in the castle to their left, and one into the castle to their right. Of course, each player will need to observe which tiles their opponents selected on each side and work collaboratively to determine which tiles will best fit each castle. Every tile has unique scoring triggers that change in value depending on where they are placed in the castle (based on their room type and other symbols on the tile’s face). The remaining tiles are all passed face-down clockwise around the table. Then all players repeat this process until there is one tile left which is then discarded. That completes round one.

Round two functions the same way, starting with a new hand of nine tiles, with the exception that the tiles are passed counter-clockwise after players make their selections. Once round two is completed the game is then scored. Players will each score one of the castles using the included score pads. Each player’s final score is the lowest-scoring castle they helped construct. The player who has the highest final score earns the favor of the Mad King and is rewarded with a night of “find your way out of this insanity you’ve built!”

The above is a very simplified blueprint of the design. But there is a bit more going on when you peer through the cracks. For example, there are bonuses for laying multiples of each room type and each room bonus is different. If you play three Food Rooms you get to draw bonus tiles from the supply and immediately pick one to add to your castle. If you place 3 Utility Rooms, you get to draw from a deck of cards that gives you extra end-game points that no other player gets. If you play five of any one room type, you get to select from a few different bonus rooms that offer big points to your castle. Knowing how to use these bonuses is key to playing the game well.

A Royal Production

When you open the box, the first thing you notice is the Game Trayz. This type of insert has become one of the hottest additions to board game productions in the last couple of years (thank you, Mechs vs. Minions). While the Trayz have a crisp appearance and certainly keep things organized, they are also incredibly functional for the actual gameplay. Once you organize the Trayz for the first time, this game will far surpass the setup time of most of your games. I clocked myself setting up a 4-player game at 46.78 seconds.

The Trayz are designed for the tiles to be loaded in sets of nine into each compartment. And each compartment has a raised middle so that you can push down an edge to lift the opposite side for easy grabbing. To set up the game, you literally pull out the two Game Trayz, take the lids off, hand each player a stack of nine tiles, a castle marker, and a scoring reference and you’re ready to play. Between rounds, there is almost zero stoppage time as you just pop out another stack of nine tiles for each player and keep going.

The tiles themselves are sturdy with a thick core worthy of your castle’s foundation. The art is stellar, and Stonemaier fans will have fun spotting references to other games. I do wonder why King Ludwig would need a Scythe room (maybe he really was mad), and why there are so many cats. If you have a feline phobia, be warned. My personal favorites are the Gallery which features characters from Charterstone and the Between Two Rooms room.

Between Two Castles is founded on tested game designs, and it works great in this new implementation. I love the “Between Two…” system for many reasons. First, it is a game that can be played at high player count; up to seven players right out of the box, for your most royally extravagant game nights. Second, the game is designed so that you must work with players to your left and right, so there is a semi-cooperative and interactive nature built-in. And third, because all actions happen simultaneously, there is minimal downtime and the game plays reasonably fast (although you don’t want to be the last player to decide on your two tiles while all other players bore holes into your soul with their impatient mead-fueled glares). The Game Trayz speed up the gameplay, and with a short play time, you don’t have to worry about set up eating the clock. Finally, it is a game design that almost any player can grasp. It’s not a mechanically complicated system, although the scoring triggers in Between Two Cities are admittedly much simpler than they are here.

I also appreciate the hidden depth of the game. The Mad King’s castles like Neuschwanstein are a perfect image for the gameplay; beautiful in appearance with a hidden labyrinth of nuance hidden behind the grand facade. On your first game, you’ll likely just be plopping tiles down to balance the room types. But as you play more, you’ll learn more in-depth strategies such as focusing on not only what you’re playing but what you’re passing to other players. You may select one tile now, knowing another tile can be played by your opponent into the same castle on the next turn, and coerce your opponent accordingly when the time comes. Some games you may shoot for a total balance of room types, while in others you may go strong on just a few rooms to maximize chaining room bonuses.

(Table) Size Matters

While the game is a beauty to look at and play, it does have some design blemishes that keep it from being a perfect production. The most glaring issue is the iconography. With a design that relies on symbol-based scoring triggers, the symbols should be clear to all players at all times. Here the symbols are just too small to see around the table, and they are all one color; white. Some of the symbols look so similar it takes some time to figure out what you’re looking at. There are seven basic room types, each identified by their own symbol, and there are four bonus rooms with corresponding symbols. Also there are a series of 4 symbols (a torch, a circular “mirror?”, a rectangular “painting?” and a pair of crossed swords) that appear on each tile as well. The bonus room and mirror are the worst culprits for clarity. I wish the bonus room icon had been much more distinctive.

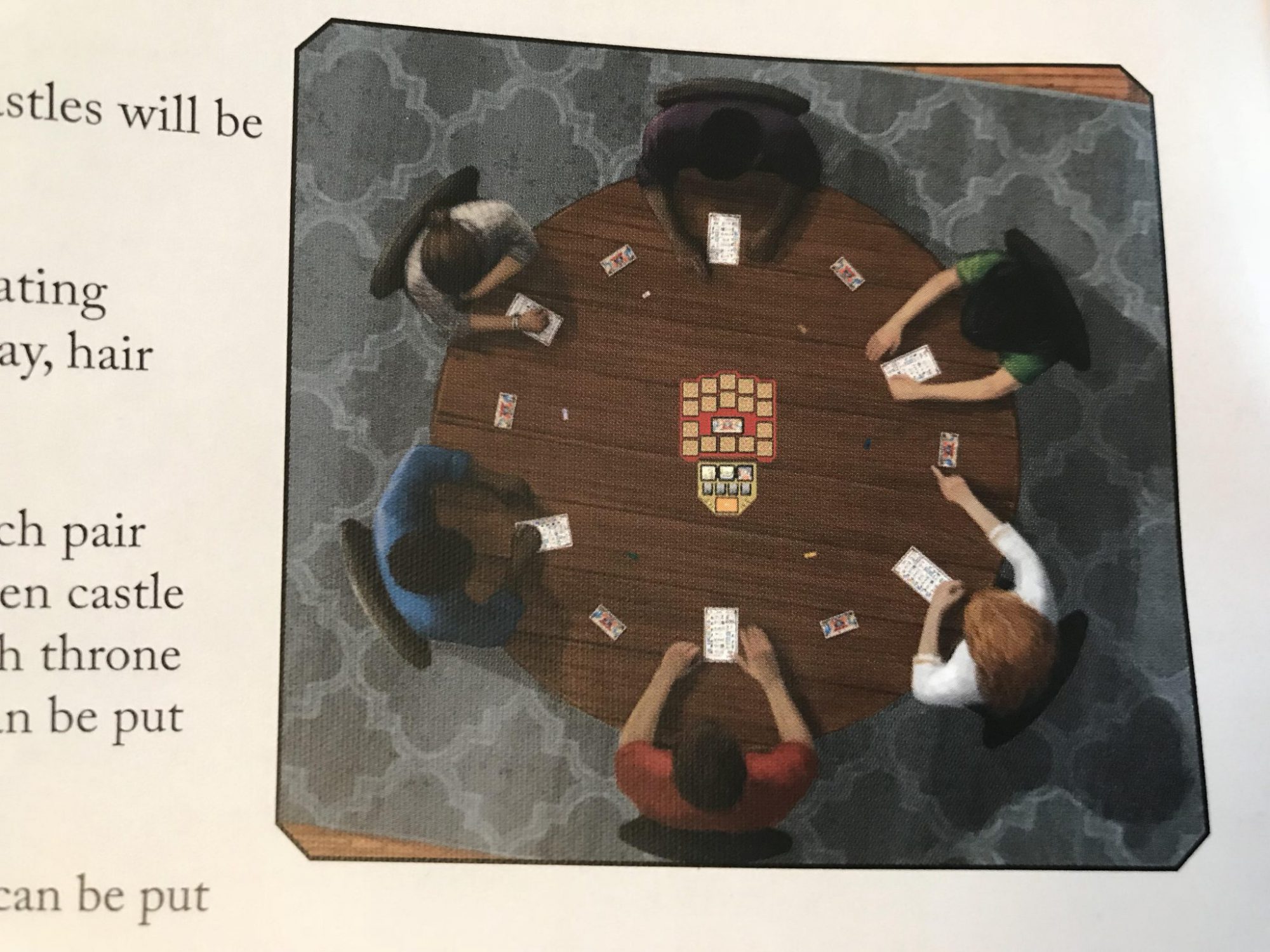

This does get easier with two conditions. First, repeated plays will help you learn what you are seeing and even learn to match background coloration with the white symbols. Second, by playing at a round table. This is one of the only games I’ve played where the shape of your table can impact gameplay to a large degree, simply due to castle spacing. The rulebook assumes you are playing at a round table. All pictures of overhead gameplay feature players sitting at a round table, and in the setup instructions it states, “Sit around a table with equal space between players.” If you only have a square or (even worse) rectangular table where players must sit across from one another, this will increase the distance between your castles and increase the time you’re craning your neck over your castle to make sure you’re reading things right.

One issue that came up in my plays was the scoring. Since I’m familiar with Between Two Cities, this felt like a natural progression to me and wasn’t a big deal. But this is a slightly more complex game. And some players thought that the scoring of the game took a substantial amount of time compared to the relative time it actually takes to play. It’s almost as if “round 3” is the scoring. Again, this is a minor thing that can be smoothed out through familiarity with the game. For the first game, I highly recommend everyone scoring one castle, as the rulebook states, and walk each player line-by-line through the scoring.

Finally, the game does have a 2-player variant. I appreciate that Stonemaier games published the variant on the box instead of listing it as a 2-7 player game. Two players will play against a third “dummy” player (King Ludwig himself!) so that each player is sharing one castle between them and one castle with the dummy opponent. One player will select Ludwig’s tiles during the entire first round, while the other player will make Ludwig’s selections during the second round. While this does offer functional satisfaction so that there is competition between three castles, it does leave a bit more lag time in the game. Since one player is controlling not only their tile selections but those of the Mad King, they must essentially play double the tiles of the other player. The player not controlling the Mad King has much more downtime. I felt that the structure of one player making all of these selections for a whole round drew attention to this wait time more. I wondered if this might be mitigated if players alternated King Ludwig control every play instead of switching after an entire round.

Building a Better Board Game

The people of the realm want to know, do the building blocks of Between Two Cities and Castles of Mad King Ludwig combine to make a solid game? Like a neo-gothic spire, Between Two Castles of Mad King Ludwig stands tall amidst the games that preceded it. In fact, I enjoy this one a little more than both. It’s not just a flamboyant “mashup” to attract fans of the two other games. This is a game that was carefully crafted;the designers knew “these pieces fit together really well and could be something greater. I love the core gameplay elements we saw in Between Two Cities meshed with similar room scoring to Castles of Mad King Ludwig. This game is more complex than Between Two Cities, but not so much that it’s an impenetrable gaming fortress. The added complexity just makes it a bit more interesting. Yet it still plays as smooth as finely ground mortar and you will find yourself competitively constructing castles with ease.

Great read and humor.