In the early Thursday morning bustle of the Essen convention hall, the lightest bustle I would know for the next four days, I came across a booth that caught my eye. Well, it wasn’t the booth so much as the game, but that can be assumed.

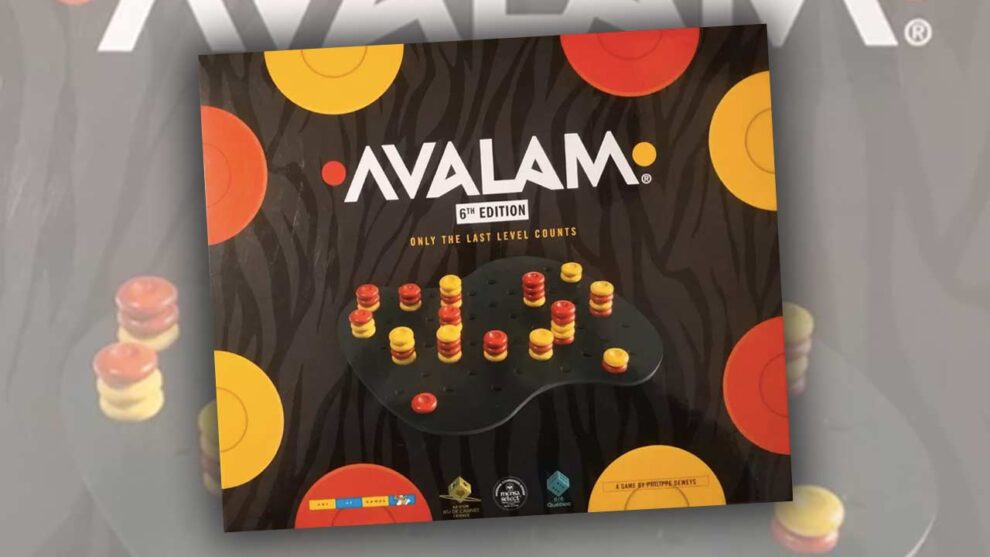

“Avalam,” the banner declared. The board was an unusual rounded shape. There were no cards in sight. The pieces were wooden circles. All at once, like a text sent to an iPhone with Echo on, the words “an abstract game” took flight in the inner sanctum of my mind.

Friday Nights I’m Going Nowhere

A man I assume to have been Vincent Sélenne, the gentleman behind Belgian publisher Art of Games, walked me through the rules. It takes about a minute, assuming you stop to sip tea halfway through.

Each player picks a color. On your turn, you pick up one piece or a stack of pieces and place it/them on top of a surrounding piece or stack of pieces. Each player controls any stack with their piece on top. The piece/stack you move can be yours or your opponent’s, but you cannot move a piece/stack to an empty space, and you cannot jump. The only other rule governing movement is the game’s most important limitation: no stack can exceed five pieces.

Play continues until there are no legal moves left. The goal is to have one of your pieces on top of as many stacks as possible come the end of the game. As with the masterful DVONN, the composition of each stack is irrelevant. The top piece is all that matters.

A Brief Correction

For the sake of his reputation, I’d like to clarify that Monsieur Sélenne did not stop to sip tea halfway through teaching me the rules of Avalam. I did that two weeks later when teaching the game to a coworker.

Saturday Night I’m Running Wild

Two or three exchanges into his first game, my friend Ryall said “Oh, so the five restriction is the entire game.” That’s just about correct. There’s more to Avalam than that rule alone, but the Rule of Five is designer Philippe Deweys’ masterstroke. It creates Go-like exchanges, interactions in which a player’s best possible decision may be to surrender an area of the board to their opponent so they can start to develop elsewhere.

You can readily math out whole sequences of exchanges in Avalam, due to the simplicity of its rules. That may make it less interesting to some fans of abstract games, and I understand that. My gut tells me that two skilled players would just about always play to a draw, but at that level players likely play for the tie-breaker (whoever controls the most 5-piece stacks).

The key is that Avalam isn’t accidentally transparent. That lack of opacity is very much the point. You know the ways in which every move can work out well for you, and all the ways in which it can backfire. That’s the center of the emotional space of the game, a zen-like state of constant panic. In my first play, I said “It’s a bit like Go…every move feels bad for me.” My friend Josh, while watching Ryall and I play, said “This is stressing me out.” Josh is a professional chess player.

I love abstract games. I love the moments of discovery that come with exploring these simple but complex spaces. They offer a wonderful opportunity to explore the variations in how games can make you feel. Circles and cubes and no story means you’re left only with the emotional experience of the decision space itself. In the case of Avalam, you feel the sharp edge of the knife with every move. Your job is to make sure it cuts the other way.

There are a few abstract games in my collection. I have owned and played many more. Most are games that I enjoy for short while and then they drift into the background. Some, however… some stay with me. Tak is an example of an abstract that has stayed with me; as is Ingenious.

Out of curiosity, how would you stack this game up against those two?

As always, thanks for a wonderful review.

I haven’t had a chance to play either Tak or Ingenious, so I couldn’t tell you how Avalam stacks up against those. I’m not sure how long it will stay in my collection, simply because there are so many abstract two-player games, and DVONN is ultimately a superior version of the same game.