The city of Recife was quiet. The streets near the prison were empty. Everyone had fled inside. Even the sun sought the cover of the horizon.

Jararaca cleaned the blood off his facão, running the blade across his kerchief. The volantes had put up a good fight, but they were no match for this band of cangaceiros. The dry, harsh deserts of northeastern Brazil do not create soft men. To survive here at all, let alone as an outlaw, you had to be tough.

Tainá put her hand on his shoulder. “Jararaca, we need to go. They’ll be sending more men.”

“Grab what you can from the corpses. We’ll head out into the mountains. They won’t be able to follow us there.”

A História

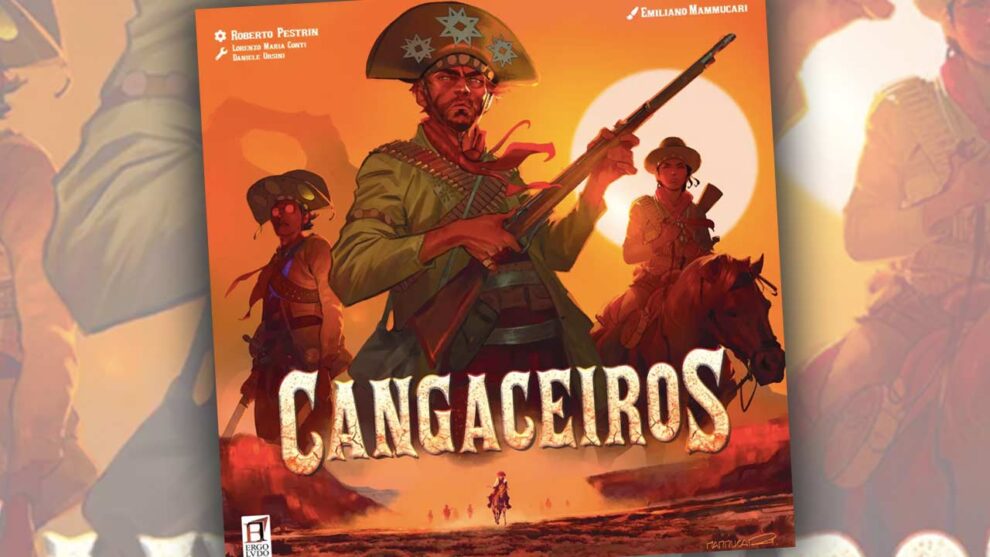

Cangaceiros has a remarkable capacity for suggesting narrative. The setting, northeastern Brazil during the Cangaço movement at the turn of the 20th century, combines with comic book illustrator Emiliano Mammucari’s superlative art to give the whole enterprise an impeccable sense of character. That box cover is divine. The character cards are full of personality, each feeling like a distinct individual. Even the volantes, who fought against the cangaceiros on behalf of the wealthy land-owners in the region, look cool. It makes sense that my imagination was fired up enough to imagine an entire film by Sergio Leone. Cangaceiros met me more than halfway.

A brief history lesson: From the mid-19th century through to the mid-20th, northeastern Brazil was home to roaming bands of cangaceiros. If they weren’t entirely analogous to Robin Hood and his Merry Men, they weren’t far off as far as public perception was and is (as far as I can tell) concerned. Cangaceiros targeted the government and the wealthy, and were often supported by poorer members of Brazilian society. The extent to which they stole from os ricos to give to os pobres is unknown to me.

The instructions play up this idea in the flavor text: “The iconic figure of the cangaceiro goes beyond the stereotypical image of the outlaw, who takes from the rich to give to the poor; it was rather someone who fought to reaffirm their rights and to seek vengeance, an oppressed countryman who took up arms against the tyranny of the coroneis (the powerful landowners who owned the fazendas, large plots of land) – because their honor was more important than anything else.”

Ares Games makes a point of stressing the nobility of our protagonists, which seems more or less in keeping with the romanticized idea of the cangaceiro in Brazil. It’s a good thing the manual takes those pains, because the game itself is only interested in the cangaceiro as outlaw, as criminal. You grow your gang, you seize control of territories, you hone your combat skills, and you get in fights with the volantes. Other than the ability to buy Fame (victory points) with money in one of the four cities on the map, which could be interpreted as distributing wealth to the poor of Salgueiro, there is no mechanic related to this idea of banditry as social protest.

The manual actively stakes out a political position—albeit one almost certainly deployed for romanticism and romanticism alone—that the game itself is disinterested in. You could even make the argument that they have contradictory political positions. Maybe whomever designed the manual has read Eric Hobsbawm, while game designer Roberto Pestrin has read Anton Blok. More likely, Pestrin came across a cool setting and ran with it.

Sandbox/Euro

I have rarely wanted to like a game as much as I found myself wanting to like Cangaceiros. It straddles awkwardly across the world of the Euro, rewarding brute efficiency, and the sandbox, encouraging exploration and fostering narrative-first experiences. I can’t decide in which direction I think the game is traveling. Is Cangaceiros a Euro that wants to be a sandbox, or is it a sandbox that wants to be a Euro?

The evidence that it’s a Euro is substantial. There are elements of hand/deck management, as you choose which three of your seven cards you’ll use every round. There are end-of-round events that punish players and scoring cards—Life Goals—that rely on an accumulation of certain resources. You choose one of two randomly drawn Chiefs at the beginning of the game, whose asymmetric special ability steers many of your choices. The locations on the map where you form Garrisons—groups of your men that participate in area majority competitions with other players—combine with your Chief to build an engine. Points at the end of the game are largely a function of all the various resources you’ve collected, including Chief upgrades.

The evidence that it’s a Euro is substantial. There are elements of hand/deck management, as you choose which three of your seven cards you’ll use every round. There are end-of-round events that punish players and scoring cards—Life Goals—that rely on an accumulation of certain resources. You choose one of two randomly drawn Chiefs at the beginning of the game, whose asymmetric special ability steers many of your choices. The locations on the map where you form Garrisons—groups of your men that participate in area majority competitions with other players—combine with your Chief to build an engine. Points at the end of the game are largely a function of all the various resources you’ve collected, including Chief upgrades.

There’s considerable evidence that it’s a sandbox. You are free, within narrow constraints, to do your own thing. Your Chief has three different Upgrades that can be activated by Training. They add fighting power, more wounds, and special abilities. In addition to placing cangaceiros on the board to form Garrisons, you can also add gun fighters and knife fighters to your Gang, increasing your fighting power. The fighting system itself, which I’ll describe in more depth in a moment, is decidedly Ameritrash, and I never use that word. Points are scored during the game by taking out large groups of volantes in glorious conflagrations.

And about those fights: they’re the best part of the game. Quick, straightforward, a little bit of math, and it’s over. There’s a risk-reward element, since some amount of the volantes’ collective strength is known before you start the fight, but they receive randomized reinforcements based on how many of them occupy the space. First, there’s a fire fight. Both parties take wounds according to the opposition’s firepower minus defense. If everyone is still standing, you rush in for a frenzied, vicious knife fight. That’s when most of the wounds happen. It is thematically enthralling. “I’m gonna knife ‘em!” was heard more than once.

My friend Andrew (no relation) pointed out that the fights were likely only so fun because the rest of the game was so boring, and I think that’s right. At a certain point, I experienced a moment of clarity: “I’d rather just play an RPG.”

Sometimes You Run Out of Headers

If Cangaceiros is a Euro, it’s a bad one. The mechanics aren’t interesting enough, the tradeoffs to your decisions are minimal. All of the best moments come from the setting and the stories that setting suggests. If Cangaceiros is a sandbox, it’s still not great. You don’t feel like the world is wide open for you to explore. Things are too samey. Oath, Cole Wehrle’s sweeping epic about history and the nature of narrative, never worked for me as a player, but it makes a lot more immediate sense to me after contemplating Cangaceiros and its failures.

The narrative evocations of Cangaceiros happen at a remove from the gameplay. They’re there because of the setting and despite the design. It’s a strange dynamic, one I haven’t experienced before. I can’t point to a single interesting decision. The iconography takes some significant getting used to, and the first play was a lumbering one, inelegant despite the straightforwardness of the system. What I take away from Cangaceiros is that story, the excitement about encamping in the mountains for the night. The game had nothing to do with that.

Add Comment