The world needs more board games born of nature documentaries. I guess it wouldn’t hurt if designers more often tried on the animus of quarreling creatures, either.

Kelp is the first design credit for Carl Robinson, developed and published with Wonderbow Games. Deeply asymmetrical in design, Kelp pits a shark against a octopus amid a kelp forest, a two-player salt-water game of cat and mouse. Deck building versus bag building. Cards versus dice. A Lego (for moment, anyway) vs. Mahjongg.

The Octopus

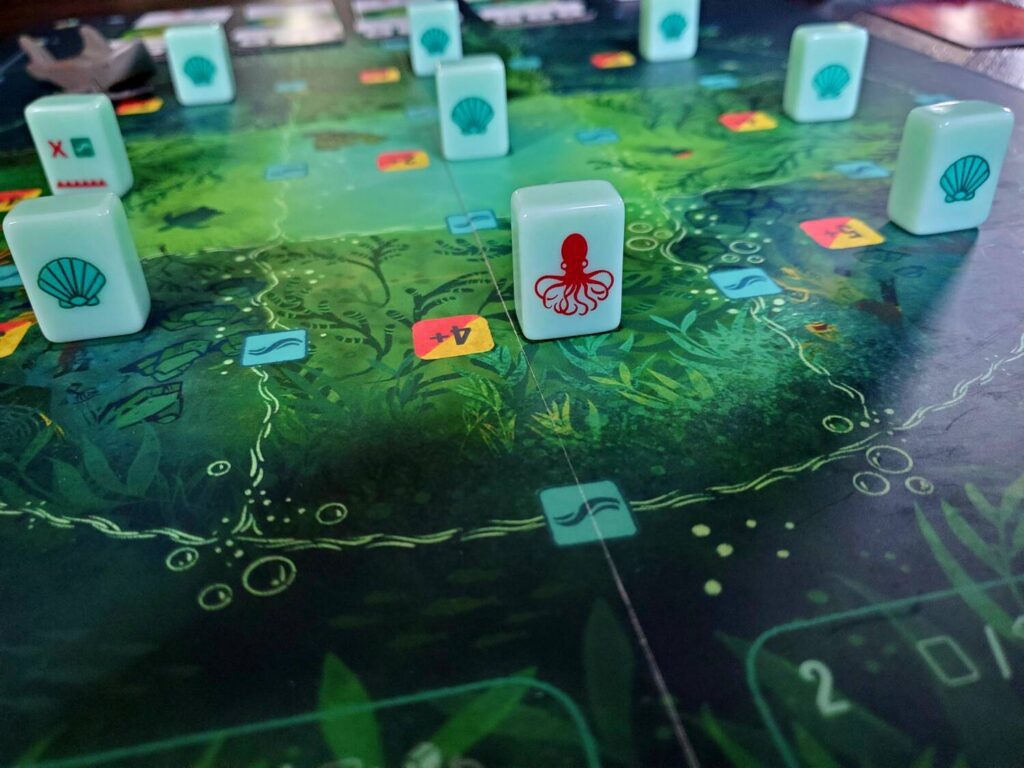

The octopus’s game is one of survival. The kelp forest is divided into a 3×3 grid, each containing a standing tile facing the octopus player. One tile is the octopus. The others are divided among shells, traps, and (potentially) octopus food.

Players choose two actions in any combination: play a card, draw back up to the hand limit, or discard to hide a revealed tile. Each card bears a cost of revealing zero, one, or two tiles. The actions include learning (adding cards to the deck), swapping adjacent tiles, shuffling tiles randomly, hiding tiles, and eating.

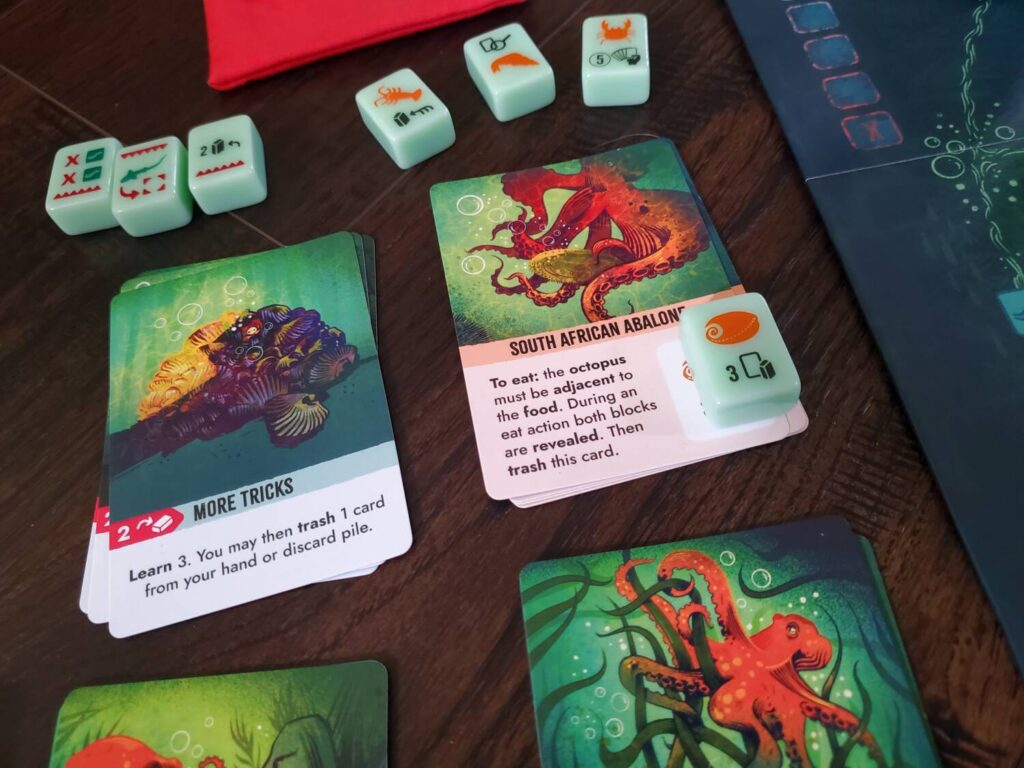

The octopus’s aims are twofold: outlast and/or eat. If the shark reaches exhaustion in the hunt, the octopus is victorious. Eating all four food options also results in instant octo-victory. In order to eat, though, the tentacled player must first add the food card and tile to the game via learning and then, upon chowing down, reveal the location of both octopus and food. Each food consumed provides a power boost, creating all the motivation needed to engage the tension.

Aside from stealth, the octopus’s only weapons are traps. If the shark ever reveals a trap, there are consequences that affect the board state. Traps, too, are gained by learning.

The Shark

The shark’s turns are a bit more procedural, but also quite simple. The toothy one draws two dice from a bag to roll and employ. Blue dice placed along travel lines represent currents that propel the shark beyond the allotted one space movement. When currents are arranged on the map in descending order, they enable chained movement. Yellow dice reveal octopus tiles, provided they are rolled high enough to exceed the threshold of success. Red dice, which also require successful rolls, enable strikes against the octopus’s secretive tile configuration.

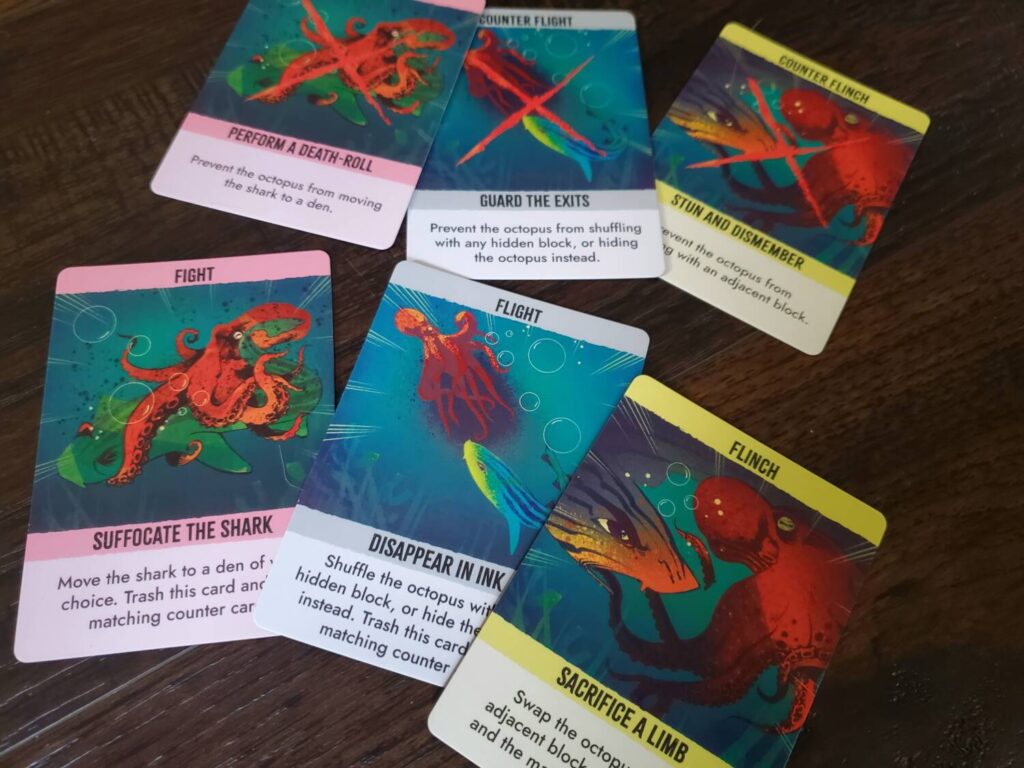

In the event of a successful strike against the octopus itself, the players enter a battle of wits to decide the game. The octopus has three specific action cards for this circumstance, the shark possesses the counter-card. Both players select a card in secret and reveal. If there is a match, the shark counters and wins. A mismatch allows the octopus to carry out the evasive maneuver, continuing the game. However, after this first duel, the matching set is removed, leaving now only two matched cards and, thus, a 50-50 chance in the next shark strike. A third strike is a guaranteed victory for the shark.

The shark bolsters strength in two ways. Used search dice and the first activated current die in a turn are applied to activate a series of abilities that each require three dice to unlock. As the game rolls on, the shark gains the ability to reroll dice and upgrade with ease. The second way is a market of single-use ability cards. Any unused dice on a shark turn land in a purse of sorts that the shark uses to shop based on the number of pips. After three dice, purchase is required. These market cards add dice to the bag as well, shifting the balance toward searching and striking.

The shark’s weakness, however, is a track of eight dice leading to exhaustion. Used strike dice automatically land in this track (removing them from the game). Every card purchase also places one die permanently in the track. If you do the math, you see there is a limit to enhancement and attack. The shark must move with hasty precision.

The experience

Playing as the shark is an internal conflict from start to finish. You absolutely want to establish available currents on the board for the future, but you also want to utilize them early and often to activate those rerolls. You want to shop early and often for the special cards and extra strike dice, but those purchases kickstart the exhaustion track and an early demise if a host of terrible rolls end up in the purse, too. When you have the strike dice, you are tempted to launch a blind attack on a good hunch, but there are only so many opportunities to flail about before you run out of gas.

Playing as the octopus is suffocating. Everything you want to do that is of any worth requires revealing some piece of information to the shark. Eating is so very tempting, but once you reveal your position you have to have the cards to hide, shuffle, and swap your way to safety or it will be your opponent who eats next.

Not only are the mechanics asymmetrical, but so are the demeanors required from each side. Every turn as the shark feels desperate, as if you know your time is thin from the moment the first die hits the exhaustion track. Even the fact that you have to swim forward at all times (the “about-face” is forbidden) tickles the nerves. The octopus, on the other hand, must remain calm, cool, and collected—or die of impatience. Ill-timed snacking when the supporting hand is weak will just create a pool of worry and a prime opportunity for the enemy.

As much as I dig the vibe of Kelp, I have to think there will be folks disappointed that the game’s final moment rests on the flip of a card like some old-school game of War. I get the psychology of the conflict: Obviously it’s best to move the shark to the other side of the board, but the shark knows that. In fact, the shark knows that I know that the shark knows that, so I should just do it anyway because it’s the last thing the shark will expect. The decision is always interesting, but that doesn’t necessarily make it exciting. I think it fits the theme well, so I wouldn’t suggest a change, but I have to wonder at the eventual response. A lot of systematic work can unravel in a hurry if the “wrong” card sees the light of day.

My second potential issue might already be solved for all I know. I feel like both sides, but especially the octopus, could use a little more spice. I’m not entirely sure where it is needed, but it’s needed. The team at Wonderbow has already announced an expansion pack of cards with a race for secondary goals and lasting benefits. Maybe this is the answer, but the stock collection of actions makes you wonder if there couldn’t be just one more trick up one of the octopus’s many sleeves or something else to enliven the fact that your ultimate goal is, primarily, hiding.

Speaking of the octopus, eating, as a strategy, is an exercise in self-flagellation. In our first couple games, when I was the shark, no one would try it. The cost seems too high. When I finally sat down as the octopus, I went for it. I had a hide, a swap, and a shuffle in hand when I reared my head for a bite. My location was compromised for the rest of the game. I lost. I was hesitant to do it again after that. Even with shuffle cards in hand, there were so many revealed tiles on the board that it was hard to get back into the safety of the kelp. I get the feeling the octopus shouldn’t attempt eating as an end unless all of the food has been added to the deck, unleashing a frantic, overindulgent sprint toward the finish line. Learning those food tiles onto the map (grammatically wonky as that phrase may be) is the ideal way to exert pressure on the shark and create an exciting duel.

There is a delicate balance in the octopus cards. If it’s too easy to hide tiles, the octopus will dwell in impenetrable secrecy. If the challenge is too great, the shark will have a full belly. Once you settle into that pocket, the difficulty of the octopus is just how passive the turns can feel. There are consecutive turns of hiding just to cycle the deck and, hopefully, build an ideal hand. That sort of patience might not be everyone’s cup of tea. It wasn’t for all my opponents.

The shark definitely has options and feels more active from the start. It’s just a matter of weighing priorities under the pressure of a ticking clock. I appreciate the extent to which Mr. Robinson has laden Kelp with the personalities of its character-creatures. This sea is teeming with idiosyncrasy.

Seeing the forest for the kelp

Kelp is just as intriguing as I hoped it would be when I listed it among my most anticipated games of GenCon. I have never played a game quite like it. I am excited to see the final production—the prototype is pretty (even the stand-in Lego shark is charming). I am curious for the campaign and any possible reveals. I want to know more about the expansion pack.

I suppose, as far as game previews are concerned, Kelp earned and has sustained my attention. There is a sea of potential and a compelling experience in the box. Check out the Wonderbow campaign when it hits Kickstarter.

Add Comment