Two of my friends love Innovation. They play it constantly. Both backed the new edition while it was on crowdfunding, and every time I receive a review copy in the mail, they vibrate with the possibility that it might be Innovation Ultimate.

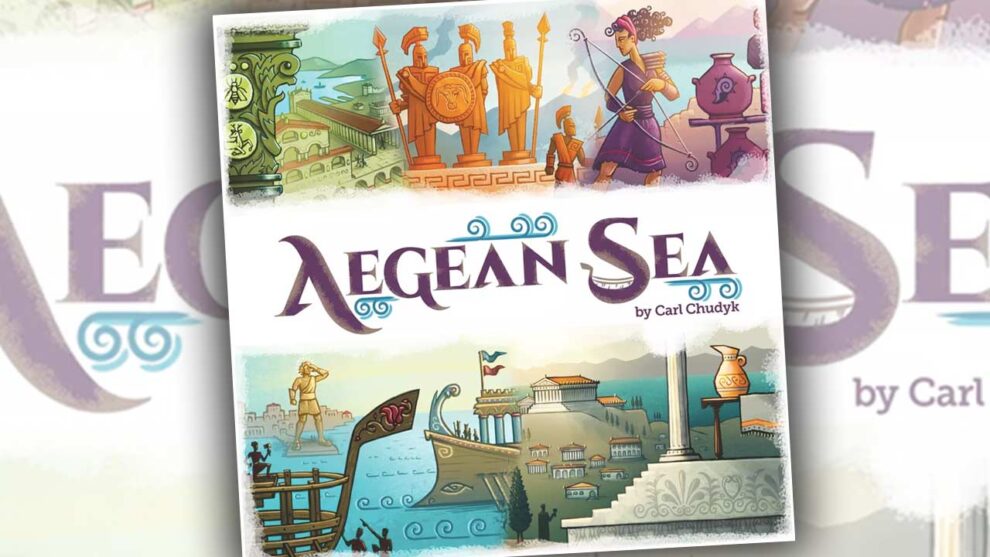

I sat down with one of them to give Aegean Sea a crack, since Carl Chudyk designs are often a bear to learn. It’s not that his games are all that complicated; the issue is that they are deeply uninterested in any notion of “intuitive.” That isn’t intended as a criticism. He’s a unique designer, and his idiosyncrasies are what make him distinct, but it is a barrier to entry. Anyone who’s ever tried to teach Mottainai knows.

Even with experience, we found ourselves struggling. On top of the unintuitive rules, there are no labels anywhere for the various and numerous tucked cards. Chudyk loves a tucked card, and in all of his other designs, the locations in which those cards get tucked. Not so here. What’s more, this is Chudyk’s first asymmetrical design.

There are five groups in the game—Athens, Crete, Ephesus, Rhodes, and Sparta—and each plays differently. Not like Root, not in mechanically distinct ways, but they necessitate significantly different strategic approaches, and do little to suggest how you’d go about realizing those strategies from the jump.

We set everything up, I started to take my turn, and after a few, stumbling minutes, my friend said, “Do we really want to play this?”

We Didn’t

Why does this design seem to falter where each of Chudyk’s bugnuts masterpieces soar? It’s not just the impenetrability. Eventually, I got past that, and it still didn’t work for me. Chudyk’s games are known for their absurdity. They’re games you can play well—I dare anyone who says otherwise to emerge unscathed from a two-person game of Innovation against a seasoned player—but they thrive on chaotic combinations, on unpredictable interactions of cards. They are, in a way, games that exist specifically for edge cases, for the obscure and unforeseeable crevices in the corners of a rule set.

Despite all their complexities, which reveal themselves over time, Chudyk’s games have appeal because you can accident your way into an incredible turn. That’s why first-time players, who are otherwise completely lost, come back. You get a taste of what expertise will bring you. Aegean Sea doesn’t have that. If—if—there are great, comborific turns in this game, or even interesting turns for that matter, they’re in the attic above the skill ceiling. There are many great games that reward experience and require familiarity to truly sing, but the best of them also offer the thrill of discovery from the first play. Until you reach expertise, these are uninteresting waters.

Playing Aegean Sea well, assuming playing it well is possible, seems to require a phenomenal familiarity with the various decks, and the 220 cards amongst them. That’s well and good, but playing well shouldn’t be a condition for enjoying a game. It should make a game appreciate over time, but I strongly believe there should be something fun or interesting or compelling that first time through.

The problem, then, is a brutal and cosmically unfair one: when a game is this superficially similar to games I’ve already been playing for years, and there is no chance of the game revealing its true self until I have played it dozens of times, why wouldn’t I play another round of Innovation, Mottainai, or Glory to Rome instead? Maybe Aegean Sea is incredible. I harbor the belief that it might be. I won’t be the one to find that out, though, and I suspect most people won’t.

Add Comment