The British Empire was having a bit of a time in the aftermath of World War II. To put it succinctly, the empire was crumbling. Colonial subjects had fought alongside the British in WWII, and now they returned home with military training and a sense of self-worth. Those pesky natives, you know. Don’t they appreciate that we brought them crumpets, cricket, and the eternal gift of an inbred’s face on their money?

The British Empire was an exquisite PR machine, telling its citizens and the world that this empire was different, sharing care and civilization with the savagery of the world. Never mind the fact that every empire has told that lie. For some reason, this time, it took. When she died, people were shocked—shocked!—to hear of the things that happened under Queen Elizabeth’s reign. Most people didn’t hear about them at all.

Flip a COIN

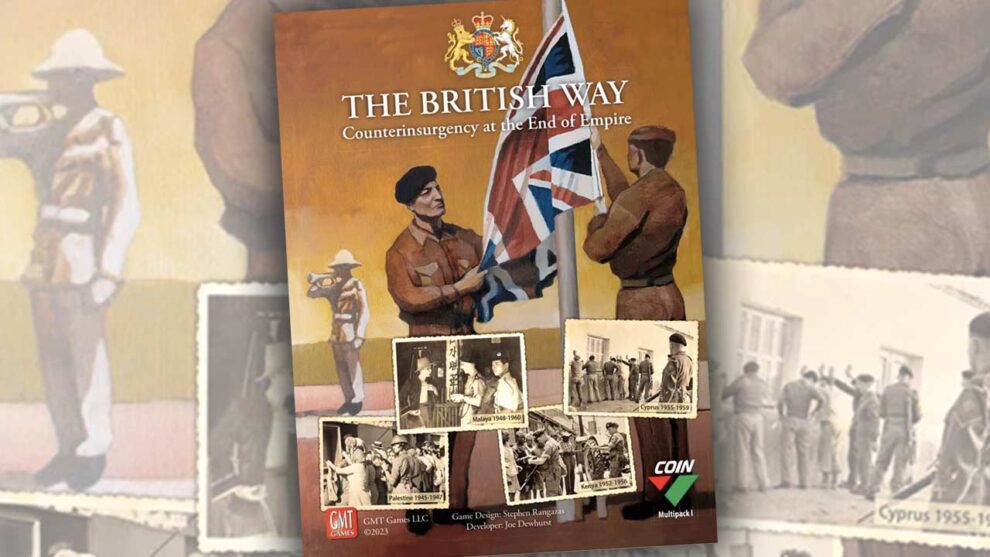

The British Way: Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire is one of the more recent entries in GMT’s popular COunterINsurgency (COIN) series, an ever-expanding collection of titles about guerrilla warfare and resistance movements. I don’t know enough about the politics of the series to delve into that, but I know enough to know that they are a hot-button topic. There is at least one writer on staff at Meeple Mountain, Thomas, whose thoughts are deeply negative.

His critiques are varied and substantial. My favorite is that the COIN series presents you with the How of what each faction does in their struggle, but it does nothing to contextualize the Whys. He’s not wrong: it’s easy to play Andean Abyss and never wonder about the motivations for any given faction, be they Marxist guerrilla fighters or right-wing death squads.

Beyond that, series creator Volko Ruhnke does work for the CIA. You have to ask questions.

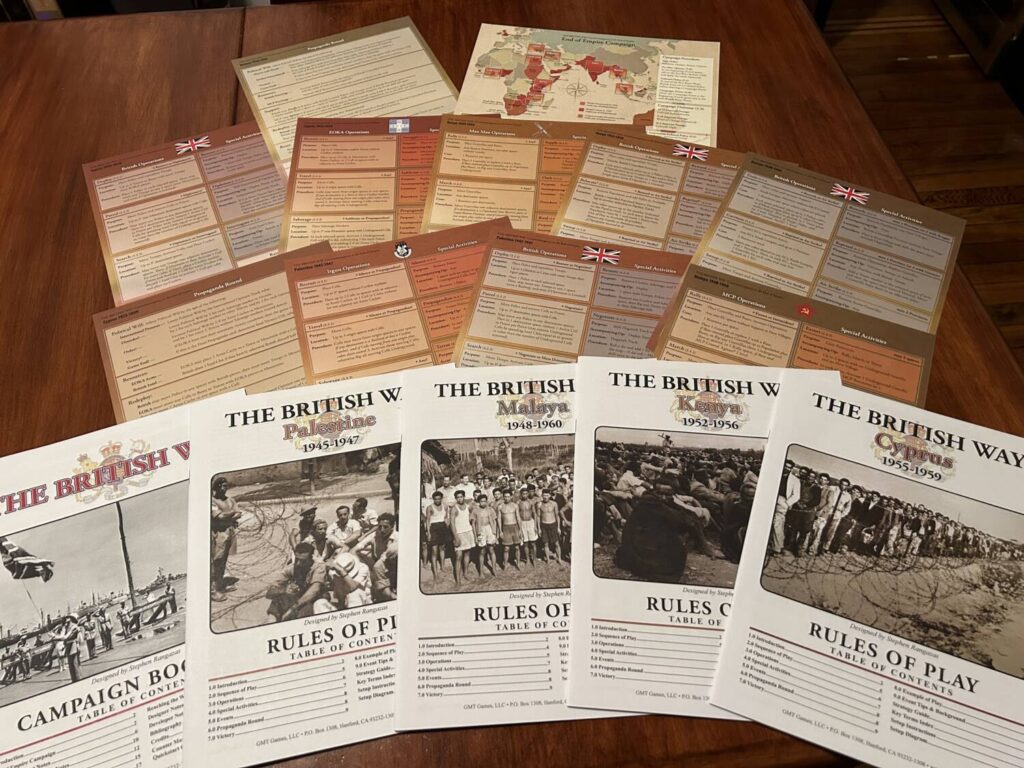

The British Way is solely designed by Stephen Rangazas, and in lieu of a single game that spans hours, the box contains four shorter two-player games, covering various mid-century conflicts. You have to “manage,” as the British called it, four different emergencies: The Zionist paramilitary organization Irgun in Palestine, the Malayan Communist Party in Malaya, the Mau Mau insurgency in Kenya, and the EOKA (National Organization of Cypriot Fighters) in Cyprus.

All four games use a similar ruleset, with minor adjustments from one to the next, mostly to allow for an accurate reflection of the differences in approach employed by the involved parties. The flow of play is uniform, and pleasantly elegant:

- The top card of the event deck is revealed.

- The player with initiative chooses from one of three options—Limited Op (a standard action), Event (activating the action on the card), and Op & Special Activity (a standard action with added paprika)—and either executes their choice or passes.

- The second player chooses between the two options the first player didn’t choose, and either executes their choice or passes.

That’s it! That’s the structure of a round. Super-simple, which is great, because the decision making is not. Each faction has three or four Operations available to them, all simple enough to operate. Your choice of action even has a little extra tension around it, since the weaker the action you take this round, the earlier you get to go in the next. Because war games have such a weighted reputation, I always experience a jolt of glee when I encounter such gamic touches.

Campaign

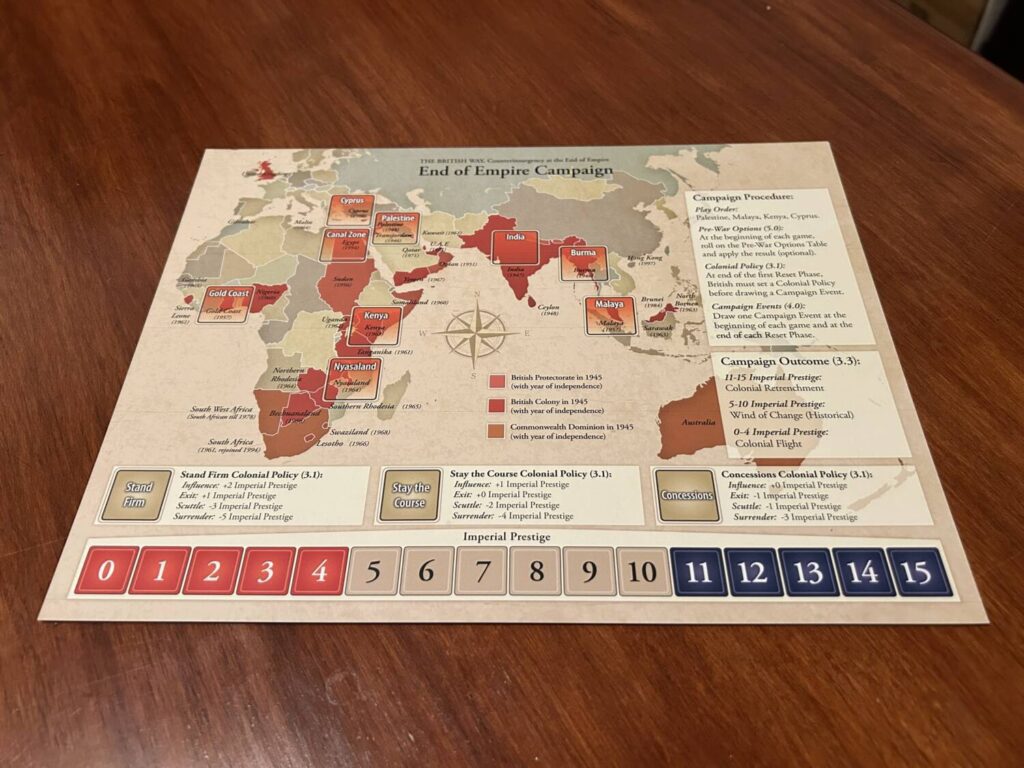

The strategies for each faction reveal themselves with repeated play and through trial and error. Fortunately, unlike Fire on the Lake, it’s easy to get in a few rounds of The British Way. You don’t need to sign up for a week-long cabin retreat. Each game takes about 90-120 minutes. Once you’re comfortable, you can break out the full campaign, which weaves all four games together, sequentially, to replicate the experience of collapsing empire.

The reason empires are so, uh, finicky about quashing uprisings in any one location is because rebellion has a nasty habit of cascading. You have to dedicate resources to active suppression, and that means you have to diminish the amount of resources you have available elsewhere, which means other locations become more susceptible to rebellion, and so on. The British Way recreates those dynamics in the campaign by introducing events from outside the scope of these four games. For example, you may have to decide between a loss in global standing or removing some troops from the map, because you’ve sent them off somewhere else. It’s death by a thousand paper cuts.

The wonder of the campaign mode is how little it adds in the way of overhead. It takes no time at all to incorporate the campaign elements into your game, and what’s more, it’s easy to walk away from the campaign and come back later. Jot down a few notes between games, and you can resume this next week. Playing it all at once is pretty great, though.

It occurs to me now that the title, The British Way, is satirical. When you read it, you think of stiff upper lips, Queen and Country, Keep Calm and Carry On, and so forth. The British Way makes the argument that the British Way is more about mass imprisonment and subjugation than it is those delicious crumpets. At last, a COIN game seems a bit more concerned with the Whys.

Add Comment