Appearing in later editions of the One Thousand and One Nights, the stories of Sinbad the Sailor tell of a wealthy wayfarer who sails out on seven different journeys. On each of these journeys, calamity ensues and Sinbad is left destitute and adrift. But, using his wits and resourcefulness, he is always able to recoup his losses, exact his escape, and return home with delightful (and I daresay, lucrative) tales of his exploits. At the end of his seventh voyage, he decides he’s had enough of sailing and finally hangs up his hat for good.

Overview

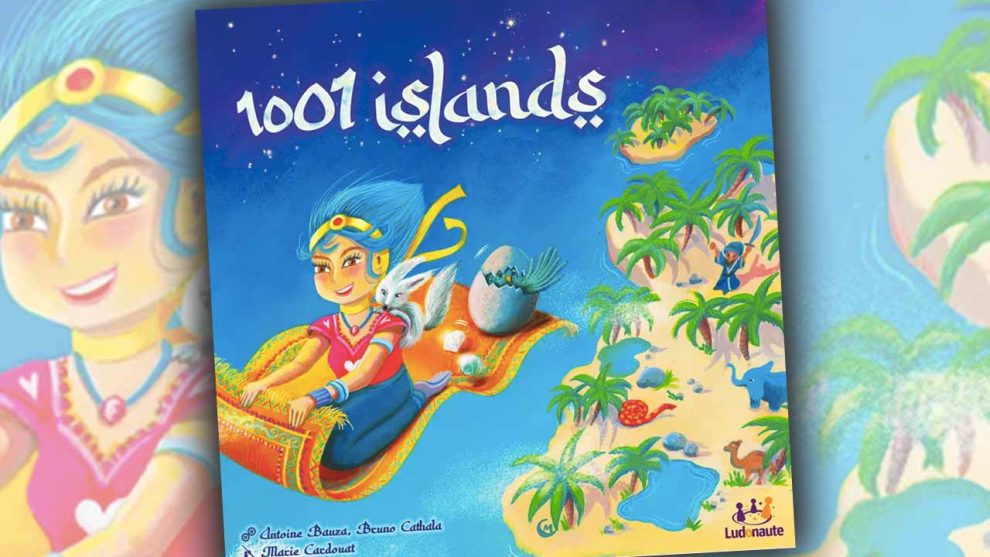

1001 Islands, the newest collaboration between Antoine Bauza (7 Wonders, Hanabi, Tokaido) and Bruno Cathala (Five Tribes, Kanagawa, Kingdomino) picks up sometime after that seventh voyage. The players take on the roles of Sinbad’s progeny as they voyage off on their own to rediscover the wonders described in their father’s tales—and presumably to determine whether he was telling the truth or just full of it—and, hopefully, create some stories of their own.

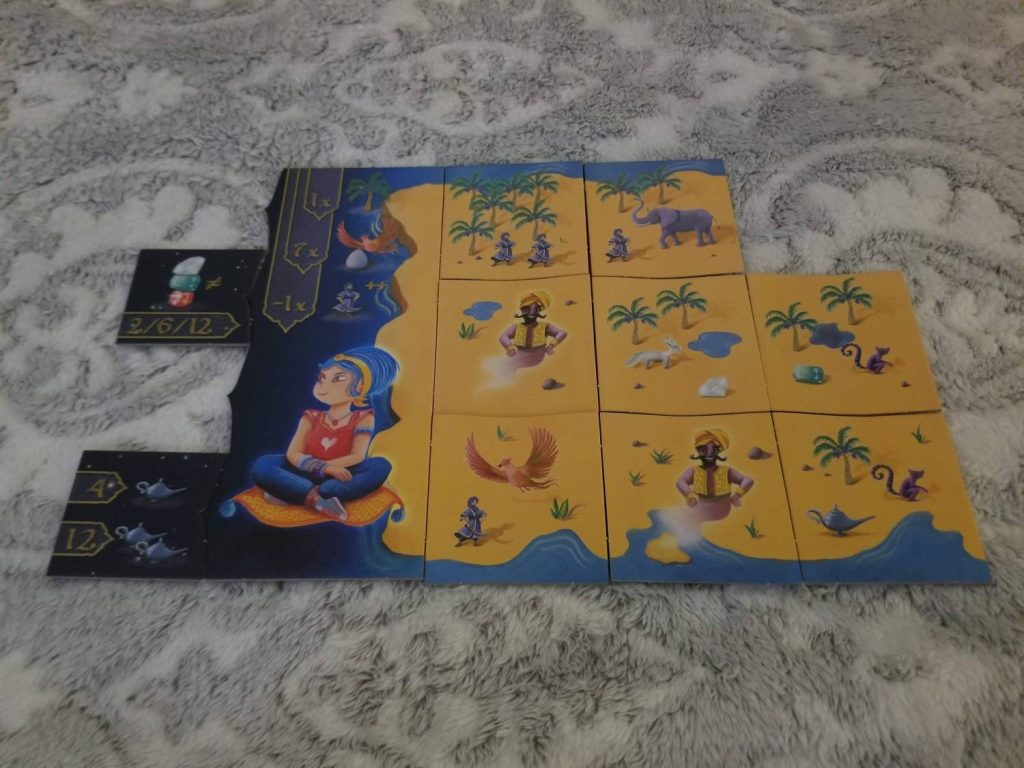

1001 Islands is a tile drafting, tableau building game. Each player’s tableau is a four by three grid composed of four different types of tiles. As the game begins, the tiles are separated by type into face down stacks. At the start of a round, the active player will draw a number of tiles from a stack of their choice (equal to the player count), select one to keep, and then nominate the next person who will then choose a tile of their own before nominating the next person in line, so on and so forth. The last person is stuck with whichever tile was unselected by the other players, but they become the first player in the following round.

The game ends at the end of the round in which the last tiles were drawn and placed. Then the players tally up their scores and the player with the highest score wins. Victory points come from several different sources: every palm tree in a player’s tableau is worth a point; every combination of a roc plus an egg is worth seven points; each of the player’s four different scoring tiles (drafted during the game) will provide some number of points; and the player(s) who has/have more bandits on their tiles than anyone else loses one point per bandit.

1001 Islands is an incredibly simple game to teach. The hardest concepts to get across are those of tile positioning and how the lamps work. Each island tile can only be slotted into a specific row and must be placed orthogonally adjacent to an already placed tile or the player’s playing board. And every time a player adds a third tile featuring a magic lamp into their tableau, they must flip the previous tiles featuring a lamp to their opposite sides, thereby rendering any of the iconography obscured this way moot for scoring purposes. This doesn’t mean those tiles are now worthless, however. There are some scoring tiles that will reward a player greatly for having flipped over tiles.

And since the tiles are so important, it bears talking about them a bit more in-depth.

The Tiles

The players begin the game with an empty playing board and any newly acquired island tiles are placed to the right of it. Each player’s tableau, their island, consists of three rows composed of four tiles each. The artwork on the tiles helps to distinguish in which row each tile belongs.

Each tile contains various images on it: eggs, rocs, palm trees, bandits, gems, etc. All of these icons are used in one type of scoring criteria or another. Other than the palm trees, the egg/roc pairs, and bandits (discussed previously), all other icons are specific to the scoring tiles.

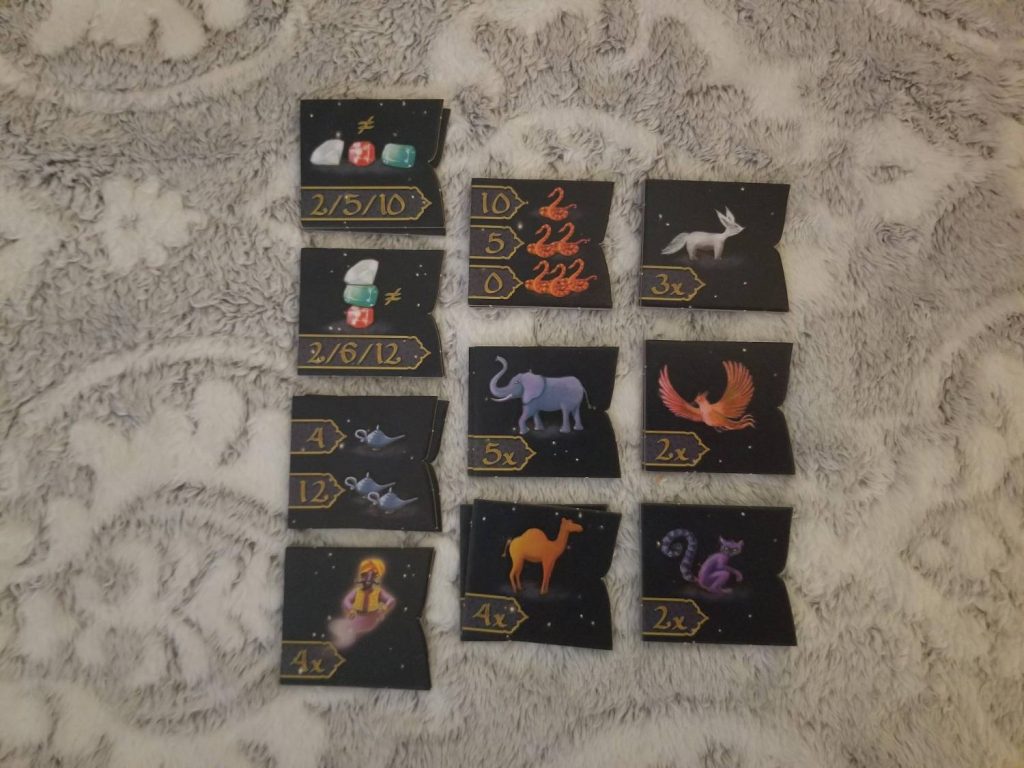

As players acquire scoring tiles, they are placed on the left side of their playing boards (the tile’s position does not matter). In general, there are five types of scoring tiles: ones that reward points for each instance of a certain type of animal in the tableau; ones that reward points for having 1/2/3 different types of gems in a row or column; one that scores for having 1 or 2 lamps visible; one that scores points depending on the number of snakes visible; and one for each tile that has been turned face down due to the acquisition of lamps.

Thoughts

Let’s get two things right out there:

- 1001 Islands’ theme is paper thin. There may as well not even be a theme. In fact, the only good thing about the “theme” here is that it’s given plenty of room for Marie Cardouat’s (of Dixit fame) brilliant artistic talent to shine.

- Despite the questionable theme, I really like this game. Like a lot.

As the game begins, there’s really no strategy when it comes to which tile you want to draft as there’s no information present to inform your decision. But as the turns go by, the decisions start to become more complex, especially in a game with only two or three players. And here’s why: on your turn, you’re making two very important decisions—which tile do you take (and, by extension, which tiles do you leave behind) and which player will be choosing next?

Regarding the first, at the beginning of the game, your decision as to which tiles to take are largely irrelevant. Without any scoring criteria to go by, one tile is just as good as the next. But, as the scoring tiles are revealed and selected, things become much more laser focused. Now, you have information. You have a goal and can immediately tell how far you have strayed from that goal or how well you’re doing at achieving it. And, more importantly, you can see how your opponents are faring when it comes to their goals. This makes tile selection critical. Do you help yourself by taking something you need or do you hinder your opponents by removing a helpful option from the table? In 1001 Islands, spite drafting becomes the norm rather than the exception.

With two players, the active player is going to be drawing three tiles, choosing one to place face down, and two to reveal face up. Then the second player has to pick one. Afterwards, the active player takes one of the remaining two before discarding the remainder. This turns the game into a clever bluffing game. Is that face down tile hidden from me because my opponent knows it’s something I want? Or is it something I don’t need? Is it something my opponent needs? If so, should I take it to deny it to them? There’s a palpable tension as you stare across the table at one another looking for tells.

With three players, the active player is faced with an even larger decision. Not only will their choices affect which tiles are left for their opponents, but they are also effectively choosing who is going to go first in the next round. That may not seem like much, but remember, that player will have first dibs on whichever tile stack they decide to go for next. You can always look across the table and calculate a person’s score. Hand the wrong person the opportunity to go first and you just might cost yourself the game.

At four players, the game feels a lot less clever. It’s still a fine game, but those opportunities for the active player to be sly and sneaky are practically nonexistent. The only benefit of being the active player is that you get the first pick of the tiles. The second player is the one that gets to have all the fun. They’re the ones dictating the action for the next round. As such, I recommend 1001 Islands at a two or three player count.

In the end, if you can get past the lack of theme, it’s a very clever game. 1001 Islands hits all the right notes. It’s got a fantastic pedigree. The artwork is lovely. It’s easy to teach and play. And it’s lightning fast. While it’ll probably never be the main attraction, it’s certainly a worthy filler and definitely worthy of your time.

Add Comment