The pirate captain invites you into their cabin for a cup of tea. It’s clear from the look in their eyes that they’re not happy about the mutinous ideas you’ve given their crew. What do you do?

Winds howl as wintry blasts rip through the abandoned hospital. Ahead you see a figure frozen in ice. Inside their outstretched hand is the keycard you need. What do you do?

The wailing robot crawls over the volcano’s rim, seeking its lost child. The AI inside you roars with sympathy, but the droid in your pocket twitches nervously. What do you do?

“What do you do?” is the central question of most roleplaying games. It’s particularly important in Atma, a new RPG from Meromorph Games currently on Kickstarter. Using only an array of cards and a pair of 6-sided dice, Atma offers a high-adrenaline thrill ride in a cyberfantasy world over the course of a standalone 2-hour session.

Beyond the Dungeon

The brothers behind Meromorph — Kevin and Matthew Bishop — have a history of producing beautifully unique games. While Shipwreck Arcana may be their best-known title, their first game Norsaga remains one of my personal favorites.

Atma is Meromorph’s first venture into RPG territory and this light card-based RPG is built to cater to new gamers. There’s no prep or advance knowledge needed, save a quick read of the short rulebook. The game follows the traditional RPG structure: one Game Master (GM) guides the story for 1 to 4 other players who each act as their own character.

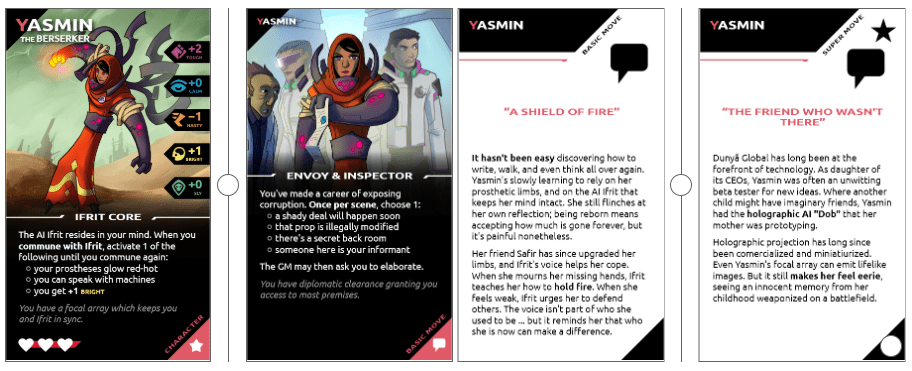

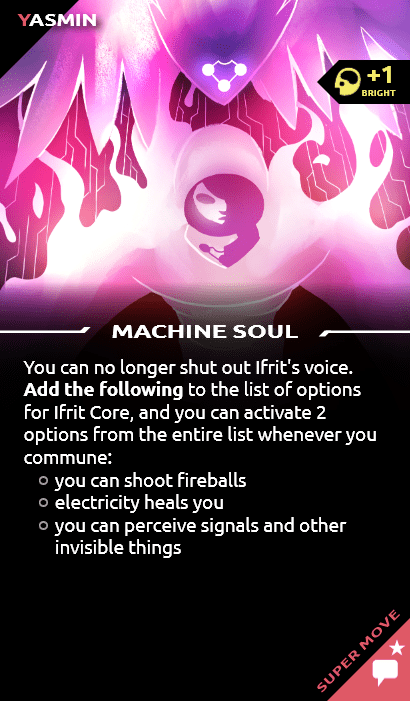

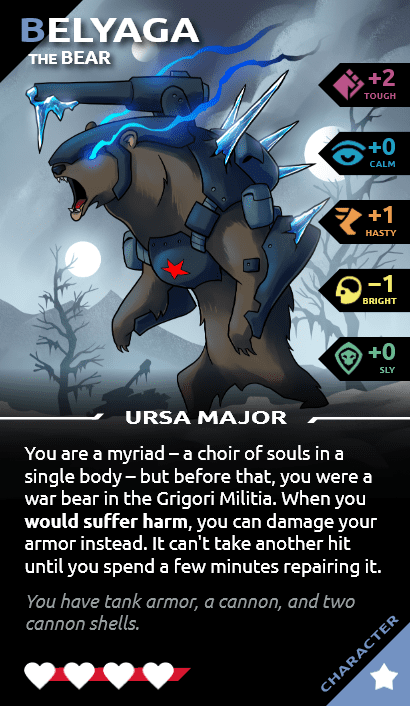

One of the ways Atma makes the game accessible for those new to RPGs is by handing out premade characters, yet there’s an important twist here: the prebuilts aren’t composed of a single sheet but a slim deck of cards, making each play slightly different. Each character has their standard character card that shows the character’s stats as well as a default move, a handful of basic move cards, and a few super move cards.

To set up, the player places their character card and one basic move card face-up, another basic move card face-down and one super move face-down. They will also place a reference card displaying the five general moves available to all characters. These moves represent the abilities the character has access to; as the character advances through the story, they’ll unlock more by flipping over those face-down cards.

Using a move is based on the Powered by the Apocalypse (PbtA) model: a player declares what they want to do then rolls two six-sided dice, adding or subtracting the appropriate character stat. A result of 7+ is a partial success often marred by GM-determined complications; a result of 10+ is a critical success.

The PbtA system is a surefire winner that’s been used in many great games and the Bishop brothers have specifically cited Dungeon World — which earned a place on our D&D step ladder — as a major influence on Atma. This isn’t just a card-only clone though. The switch to cards makes Atma easier to access and understand than most PbtA games.

Having the prebuilt characters be distinct individuals rather than archetypes gives new players a clear path to roleplay: they’re not just “the healer” but Maud, a supergenius doctor with her own powerful regenerative abilities and a keen fashion sense. To facilitate this each card in the character’s deck offers a slice of their backstory. These tiny snippets are fun to read and often add context to the special abilities. They can also help the GM come up with ideas for the current scene.

Running the World

The GM should be happy to get help from the players because a session of Atma is intensely creative. While the system itself isn’t complex, the stories it creates certainly can be.

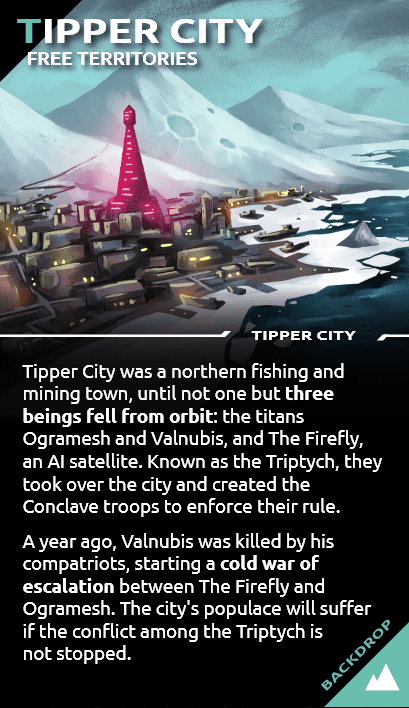

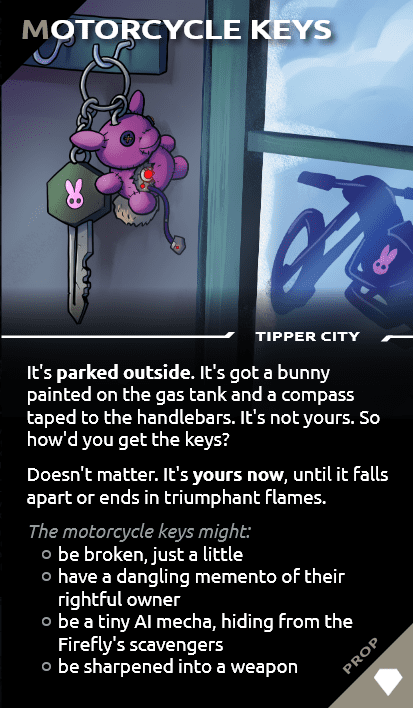

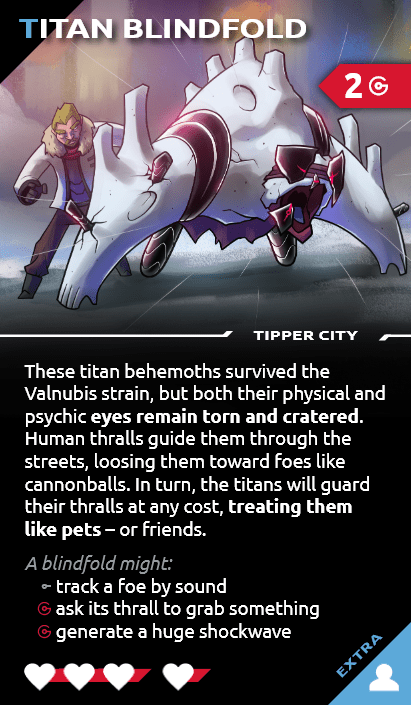

Just like the players, the GM will rely on the cards to shape the game. First, the group will have to pick a single stage for the session. This is the basic setting, the corner of the world in which the characters find themselves when the action begins. Each of the 4 available stages to choose from come with their own decks which will all feature in play. These include the backdrop card, which defines the stage; the story cards, which determine the players’ ultimate goal; the scene cards, which indicate smaller steps to achieve the story goal; and the prop, twist, and extra cards, which will be used to add complications or assistance for the characters. The GM will also receive their tokens, the currency used to play many of these cards as well as take certain actions.

To start, the GM will place the backdrop and a story card face-up. Each story card presents an overarching aim for the session as well as any special rules that may apply. Next the GM will deal three random scene cards: each of these is a smaller setting with a pair of goals to choose from. The players can collectively decide which goal appeals the most in each scene. They’ll need to fulfill a goal in the first scene to progress to the second, a goal in the second to progress to the third, and both the third scene goal and the story goal to finish out the session.

Seeing those first few cards splayed out is intimidating. How can a crashed airship, a restaurant, and the rim of a volcano possibly fit together? The beauty of Atma lies in taking these random elements and finding the connection points between them.

Whenever the GM gets stuck, they can spend tokens to introduce an extra, plot or twist card to the session. These feature non-player characters (NPCs), useful objects, and minor events respectively. Playing one or two of these lets the GM add threats when the characters get too comfortable or give them an out if they’re stuck in a boring scene. The tokens can also be used to directly harm the characters through anything from environmental effects to an attack.

Dealer’s Choice

What I find most appealing about Atma is how chaotic it is at first. This is a game that will test its players’ improv skills. As with most improv sessions that can sometimes lead to zaniness. The term “gonzo” — first popularized by the journalist Hunter S. Thompson but often used to describe RPGs — comes to mind. The gonzo style is over-the-top, ham-fisted, leveraging the absurdity of situations for laughs. If that’s what you’re after you can definitely find it in Atma. This is a game, after all, that features a playable talking robo-bear with a cybernetic cannon.

Yet there’s another layer here. As threads start emerging the game can take on a more serious tone. There’s plenty of room for nuanced character moments if you want them: the wave of fear that subsumes the character stalked by an interdimensional being or the pang of regret over a fallen friend. These characters, as weird and wild as they are and as bizarre as their adventures may be, still feel human.

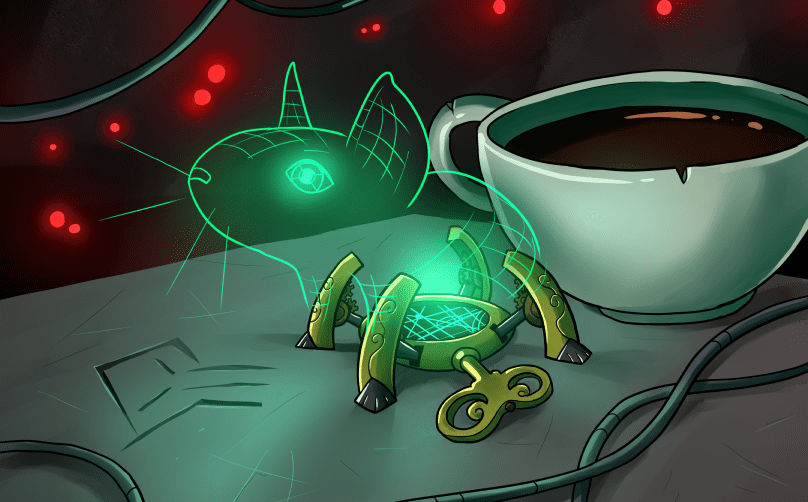

The cards themselves are gorgeous. Matthew Bishop is one of my favorite artists in tabletop games and in my opinion this is his best work yet. Glancing over the art sets the mind whirring like a clockwork mouse. Each deck is packed full of clever details and strange creations, a playground of ideas brought to life in lush color.

The art offers a lifeline into the world of Atma — and it is a fully fleshed-out world, even if it’s only conveyed through cards. There’s a surprising amount of depth to the lore that can at times be overwhelming. Even the starting set’s backdrop card, Tipper City, plunges players directly into the middle of a 3-way cold war between factions led by alien beings, one of whom recently died and left behind a sizable power vacuum. That’s a lot to convey on a single tarot-sized card! It’s well worth scanning the various decks before playing to get a sense of what’s even possible.

Atma is intended to be playable by everyone, even total RPG novices, in 2-3 hours. For the most part I think it hits that brief. It’s visually appealing, action-packed, portable and easy to learn. However, in my personal experience the GM role feels a bit harder to manage well than some other games since it leans so heavily on improvisation. While someone who has never played an RPG could definitely run a serviceable session, not being able to prepare anything means that new GMs — or experienced ones accustomed to planning out session arcs beforehand — might struggle a bit.

And that’s okay. The world of Atma is a little messy, full of oddities and willing to accept a few contradictions. That world is built on a flexible narrative-focused foundation that sets the endpoints but lets players pick their own path between them. Whether that’s goofy hijinks, light hack-n-slash, or dramatic character arcs is up to you.

So: what do you do? Head on over to Kickstarter right now and back Atma. You’ll be glad you did.

Add Comment