Let’s burn some bridges today.

For the past few years, people have heavily pushed for diversification in board gaming. This includes not only getting people from different cultures to play board games but also game designers and game settings. This is understandable, considering that many board games used to be euro-centric with settings involving colonization and war.

However, for some reason, this discussion of diversification does not extend to artistic expression. Cultures all have their own ways of expressing their stories and communicating their philosophical ideas to the masses. One glance at Bollywood reveals Hindus’ love for musicals and absurd action sequences. Hollywood has shown the world the result of corporations digging their talons into artistic integrity. Japan has popularized its “anime aesthetic,” also known as Big Eyes, Small Mouth, in its media.

I bring this up because board game reviewers love to toss anime board games into the nearest Bermuda Triangle, hoping the masses will never notice them. If I sound like I’m donning a tinfoil hat, let me ask one question: when was the last time Shut Up & Sit Down or The Dice Tower featured an anime game? Precisely.

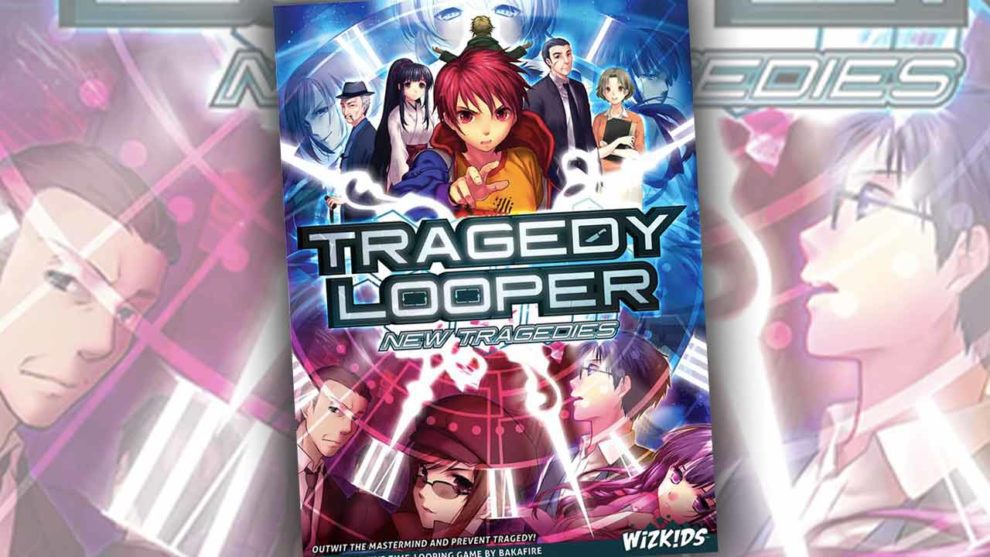

Let’s solidify this argument further by discussing Tragedy Looper‘s brief history. Z-Man Games localized the game in 2014, and it received a mixed reception. While some players loved it and called it the best deduction game ever, others wanted to send it to the guillotine line. Despite its odd cult following, several publishers released it around the world.

In 2016, Spanish publisher Devir released the game with completely new artwork, replacing anything Japanese with a generic Western noir detective aesthetic – possibly the first case of a board game getting the Netflix Adaptation treatment.

I am surprised to see this game getting a re-master in 2023 as the rules remain unchanged, except for some terminology alterations, and the game has a new art direction while still keeping the anime look. For those who own the original Tragedy Looper, every scenario here is new and it has the characters from both the original and expansions, so you can play the older scenarios.

Enough about the history or the significance of this game. What is Tragedy Looper? It’s a logical battleground between three players against one using time travel.

Rewriting the future

The protagonists, a three-player team, must survive a time loop without hitting any loss conditions based on the scenario. But what are the losing conditions? That’s the deduction the protagonists must make and if they do suffer a loss, they repeat the entire time loop again, resetting the entire board. Each scenario has specific characters, hidden roles, loss conditions, and incidents that they must navigate around. At the start of the game, the protagonists only know the characters and the scheduled incidents – nothing more.

The Mastermind, a single player, knows all of the roles and the culprits of incidents, as well as all of the conditions that can make the protagonists lose the loop. Their job is to ensure that the protagonists get as little information as possible from each loop, while the protagonists attempt to extract as much information as they can.

If the protagonists hit the limit of their loops, they get one chance to make a “Final Guess” by connecting each character with their role to snatch victory away from the Mastermind.

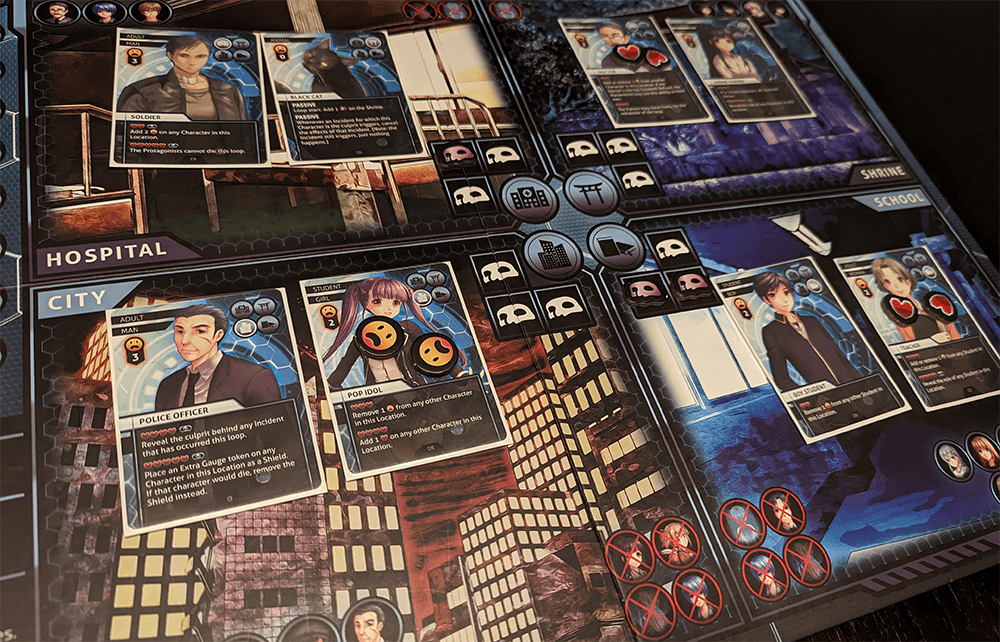

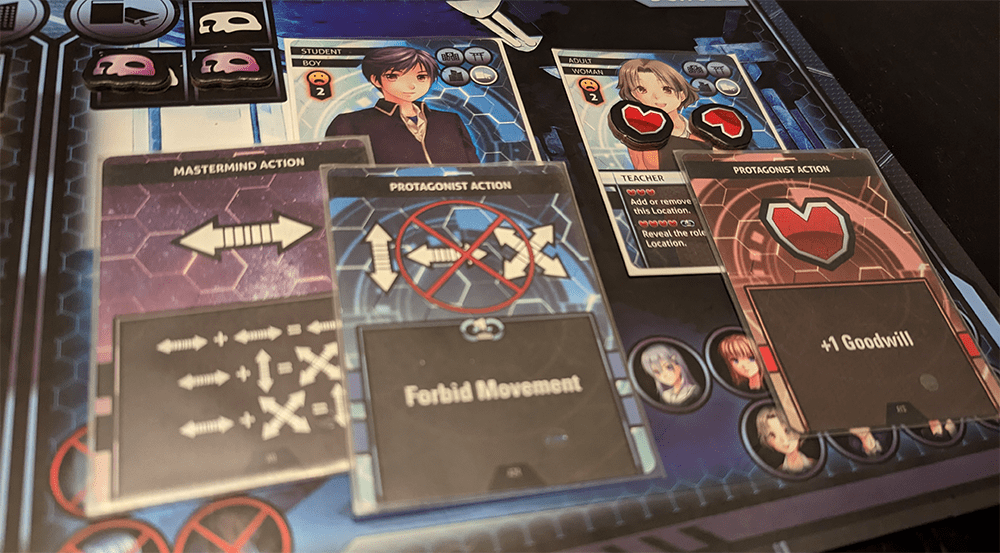

The Mastermind starts each day by laying three of their cards facedown on locations and characters, which will move characters or manipulate tokens. Then, the Protagonists add their cards, one at a time, with identical functions to the Mastermind’s. This can be challenging, as the Protagonists cannot communicate during loops, only between loops, so they must react to any new information on the fly and in silence.

The best way I can describe this system is as a mini card-programming game. Mastermind plays three cards, the Protagonists respond with their three cards, and then the cards are flipped to resolve the situation. Characters will move from location to location, tokens shift around, and then it is time for the Ability phase.

Abilities are the heart of the game. Some characters have a hidden role attached to them, and it is in this phase that the Mastermind triggers them. Scenarios themselves also have special rules that might grant another ability. It is important to note that the Mastermind will only tell you the result of the ability, never the source. If an Unease or Intrigue token is added to a character in a location, there is a reason for it.

Winning friends and influencing people

Protagonists also have abilities they can utilize. Each character has their own Goodwill abilities, and when a character accumulates enough Goodwill tokens through card play, the Protagonists can activate them. These powerful abilities can range from removing tokens to declaring a character’s role. To add an extra layer of complexity, some roles give the Mastermind the option to refuse a Goodwill ability attempt, which will make it easier for the Protagonist to figure out that character’s role.

After abilities are the incidents. If there are any incidents scheduled for the day, they activate if the culprit of the incident has reached their Unease limit. For example, if the Shrine Maiden is the culprit of a Suicide incident, the Shrine Maiden must have at least two Unease Tokens to trigger the incident. Incident activation is mandatory.

The day is over after that, and the next day begins as long as no loss conditions have been met.

I admit I presented a lot of terminologies and rules. Fortunately, the game comes with an exciting spreadsheet of a player aid that categorizes these elements into a palatable format. This doesn’t mean Tragedy Looper is an easy game. I can teach the game in less than 10 minutes since mechanism-wise, it’s quite simple.

It’s all the rules behind the scenes that Protagonists must figure out that require some adjustments since this isn’t a typical board game. The designers took this into account since the first four scenarios give the Protagonists and Mastermind the breathing room they need to become familiar with Tragedy Looper‘s many tricks. Despite this, players understanding the core basics of this game will feel like a coin flip as I had some players hating on this, while others embracing it.

Murder now, worry later

Tragedy Looper differs from many other One versus All games because the “One” player does not simply act as a referee or game master. They are a hostile entity for the protagonists, abusing the role abilities and incidents in their favor. While this does sound straightforward, some roles can act as ticking time bombs of information, ready to explode in the Mastermind’s face. A few scenarios are designed in this way, where a potential role or two must remain hidden or they could end up being the key reason why the Mastermind lost in the Final Guess. It is a contest where the Mastermind constructs a psychological prison for both themselves and the Protagonists, and as with any structure, it can be dismantled.

As if that wasn’t enough, the Mastermind must be proactive to achieve their goals by moving certain characters and adding tokens, drawing attention to their target with just one card.

For example, let’s say that the Office Worker is a Serial Killer. If the Serial Killer is in a location with only one other character, they must kill that character at the end of the day. Common wisdom would suggest that the Office Worker should not be alone with another character. That makes sense; however, this brings the Protagonists’ attention toward the Office Worker. They will scrutinize the motivations of the Mastermind. Not only that, but the Protagonists must figure out a way to squeeze this information out of the Mastermind without communicating with each other during the loop.

Red script

This is how most scenarios in Tragedy Looper work. In the first few loops, the Protagonists are scrambling for information, and the Mastermind provides some footprints for the Protagonists to follow since they must make moves to win the loop. Not all footprints lead to the truth and a good Mastermind will toss the Protagonists into a mental hedge maze that isn’t easy to get out of.

Towards the middle and end of the game, the Protagonists have a clearer picture of the scenario and will start using this information to their advantage. They are no longer making subjective guesses; they are anticipating the Mastermind’s moves and end goal.

The Mastermind, who is well aware of their situation, starts thinking of ways to counter the Protagonists’ predictions while the Protagonists will try to counter the Mastermind’s counter moves. As the scenario eventually reaches its climax, the tension between the two sides of the table becomes so thick that you can cut it with a machete. The only thing missing here is ominous chanting, a black notebook, and a bag of potato chips.

It’s a brilliant game design that deserves to be preserved for future generations, yet it’s also hard for me to recommend this one to everybody.

A noticeable expiration date

Let’s start with an easy one: there is no replayability here, which is unfortunate because, unlike a Rian Johnson film, I want to experience this more than once. Every scenario has characters with specific roles, incidents, and loss conditions. Once the Protagonists figure out most of the information, it is impossible to replay the scenario.

The box comes with 13 scenarios, most of which last between 90 and 120 minutes, but once you are done, you are done. At most, you can find community-created scenarios or design your own, and the Mastermind Handbook provides a comprehensive guide on how to do this.

Perhaps the biggest caution I must raise here is the burden on the Mastermind. You need a Mastermind player that can juggle the many interactions between the roles, doesn’t forget rules, and optimize their card play.

Your enjoyment of Tragedy Looper is chained to your Mastermind, and if that person does not know what they are doing, you’re in for a bad time. But if you find a good Mastermind player? Tragedy Looper provides an experience you will never get in any other board game. Even after this game’s release in North American shores nearly 10 years ago, no one has replicated the vibe that Tragedy Looper is going for.

Enough about that. What about those of you reading this with the original Z-Man edition sitting on your shelf? Is this worth it? 100% yes.

Makeover!

This version contains both the original and expansion characters, and the scenarios are far more balanced and interesting. With a wider variety of characters to interact with, players can enjoy a more diverse experience as they go through the 13 scenarios.

The art direction has improved significantly. I understand that the original version was attempting to create a horror visual novel look, taking inspiration from games like Umineko and Higurashi. Nevertheless, it did not work well for a board game because of excessive visuals, busy boards and tokens, dark contrast on the cards, and tiny fonts. In short, the original edition’s presentation was an assault on the visual senses.

WizKids aims to replace the horror aesthetic with a cleaner sci-fi look. They have made tokens more distinct, board information clearer, and font size more legible. This inviting aesthetic is something I am willing to accept at a loss of the original horror visual novel look. To add some personal anecdote to this, I’ve played the WizKids version more in the past few weeks than the last few years I had with the Z-man edition, mainly due to people requesting to play the newer version.

I do have a major complaint about this remaster: the writing in the rulebook. A common criticism of the original Z-Man edition was that the rule book made it difficult for new players because of a weird mini-scenario and awkward writing. Unfortunately, they rewrote little in this new version. To make matters worse, there are a few minor misprints on the player aids.

While not perfect, the latest iteration of Tragedy Looper is a welcome addition to the game’s already impressive legacy. Wizkids deserves admiration for going the extra mile to get more people to take part in this wonderful masterpiece of board game design. Even after a decade since its original Japanese release, it is still sitting on a throne that hopefully more people will notice.

Add Comment