You know how it goes. You’re walking through your local board game store, or perusing an online catalogue, when you see a cover that strikes you. Something about the title, the font, the art, it just feels right. You’ve never heard of this game before, you know nothing about it beyond what you can see, but you know this meeting ends with a purchase. It happens to all of us. There’s something about taking a risk, about the leap of faith, that makes the whole experience more exciting.

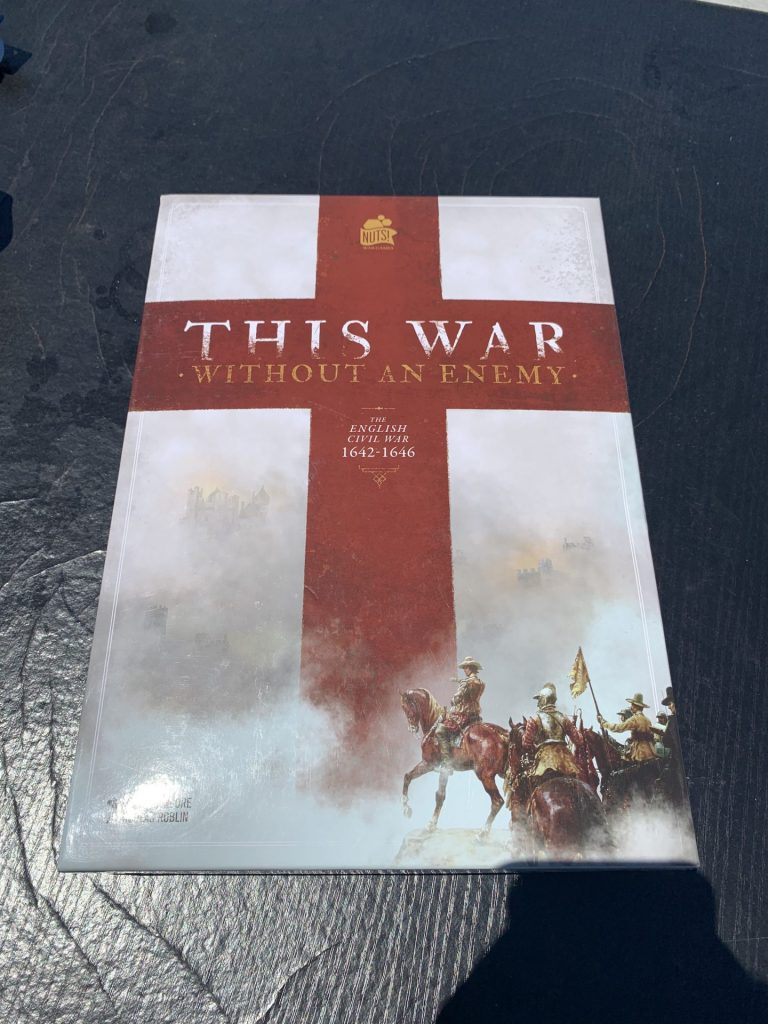

I knew the moment I saw This War Without an Enemy that I wanted to play it. Artist Nicolas Roblin’s cover, a fog-laden field with an overlain crimson cross, is a fantastic bit of work. The setting, the First English Civil War that spanned 1642–1646, didn’t exactly set my world on fire, but it seemed like the perfect theme for a heavier game to try with my roommate, who has an anglophilic streak the breadth and width of the English Channel. I’d had good experiences with the publisher, Nuts!, in the past. All signs pointed to go, and I happily went.

Occasionally, such blind buys will become all-time favorites. I bought Azul and Root without having heard a single thing about either. Most of the time, realistically, these games will be perfectly alright. Life is full of The Dwarf Kings, Big Book of Madnesses, and Happy Pigs. You’ll play them a handful of times and move them on.

There is a third, fleetingly rare outcome. From time to time, if the conditions are just right, you’ll bounce so hard off of a game you were certain you’d love that you never even finish one full play of it.

Block

This War Without an Enemy is my first foray into block wargaming, a venerable subgenre of a subgenre. As opposed to the flat cardboard chit approach of most wargames, the troops in block wargames are printed or adhered to one side of upright blocks. Your opponent(s) know(s) where you have forces, and in what numbers, but they do not know the specifics. How strong is each unit, what type of combat unit is it, etc. Block wargaming is one of the many clever ways designers and publishers have attempted to capture the legendary ‘Fog of War’, the impossibility of perfect information in a warzone.

The production value is striking. The wooden blocks are vibrantly colored, the stickers and cards are beautifully printed. The map is lush, with bold greens, though I wish it were slightly less concerned with looking pretty. While the rules for movement are straightforward, the regional boundaries that inform those rules and the names of the regions are devilishly difficult to see. Good luck finding anything if you don’t already have a strong sense of British geography.

The game is card-driven, and both factions have their own decks. Each round, the Royalists and the Parliamentarians select a card from their hand and use both its event and operation points, which can be spent to recruit new soldiers into new or existing units, or move existing units around the board. This is my first time playing a game where both the event and operation points take effect. Games like Twilight Struggle and Red Flag Over Paris give players a choice of one or the other, assigning higher operation point values to more powerful events. This War takes the opposite approach, assigning powerful events lower operation values.

The goal of the game is the same for both players, to hold enough of the cities on the map. If either player becomes overly dominant by the end of any given year, the game ends. If the war plays out in its entirety, King Charles and the Royalists need only force a tie in order to win. The status quo doth benefit those who were already in power. Throughout the game, the two players will frequently engage in battles, which are carried out on a charming tactical aid.

Bounce I

This War Without an Enemy is awful fussy.

Well, no, it’s not generally fussy. Generally, the rules are pretty straightforward. The combat is fussy, though, and there is a lot of it. I don’t mind combat but it’s never going to be my favorite part of any game, so I do ask that it at least be straightforward. Another Nuts! game I own, the absolutely lovely 300: Earth and Water—a game so riddled with translation issues that I’ll die believing it was supposed to be titled 300: Land and Sea—uses quick and easily-parsed die rolls to determine combat outcomes.

The combat here is dice dependent as well, but it’s not the breezy kind where you roll dice and the number is higher or lower than what you need and that’s that. I mean, it is that, but it’s also, well, fussy. You find yourself saying things like “I immediately open fire with my infantry, which means they are rolling with a -1 modifier,” or “Alright, my cavalry rolls for pursuit with a discipline modifier of -2 because they did more damage to your troops than your troops had health.”

It reminds me of that day I watched in fascination as two men played Warhammer, their faces buried in the prepared reference packets they’d brought for their individual armies. “That soldier has the [unintelligible], so I roll 37 dice, and because you have the [unintelligible] equipped on your [unintelligible] I only get hits on 5’s or higher. Oh, and I have [unintelligible], so actually it’s 39 dice.” I love this kind of thing for other people.

Bounce II

The early game is so strategically open-ended that neither I nor my opponent had any sense of what to do. We each selected a card, figured out turn order, and then stared at the board in utter incomprehension. “What should I…do,” I asked after a few moments. Neither of us knew. I do not have enough experience with wargames or any experience with block wargames to say whether or not that is a quirk specific to This War Without an Enemy.

Red Flag Over Paris and Comanchería, the two wargames I’ve played enough to know I love, have short-term goals in addition to the larger campaign goals. In Red Flag, players begin each round by selecting an objective card that will score at the end of the round. Comanchería breaks up its larger scenarios into episodes, each of which has its own win condition to work towards. In both games, these design choices help the player(s) guide their immediate actions in a way that gives the game thrust. Even Twilight Struggle, which I initially found mind-bendingly open, phases in scoring cards to slowly increase the scope of the active play area.

“I feel like you have to have a PhD in English history to start playing this,” my opponent said. This War Without an Enemy relies entirely on the players knowing what they’re doing to give the game any sort of momentum. That’s not inherently a criticism. It’s more of a warning. The beauty of chess, I found myself thinking, is that even inexperienced players know you go forward.

Bye

This is a niche product for a niche audience that I now know isn’t one of my niches. I am the outside intruder here. That’s okay! That happens when you explore new types of games. I neither resent This War Without an Enemy for its impenetrability nor regret putting in the time to try and understand it.

My overall impression is that the publisher, the artist, and first-time designer Scott H. Moore all prioritized simulation over game experience. The fiddly combat, the lack of prompted direction, and the More of a Map than a Game Board board are not a liability because they are not intended for anything that even approaches a wide audience. Moore has talked about changing publishers from Columbia, the creators of block wargaming, to Nuts!, and how that allowed him more freedom to tweak the Columbia system in ways that made it more historically accurate. I’m glad he got to make the game he wanted to make, and based on what I’ve read of other people’s experiences, he was successful.

But oy.

Sounds like my first impression of Wingspan. I first tried out the digital version on Steam, and went through the tutorial. After that I bought the analogue game, because I really wanted to play it, number one, because I love the theme. Reading the rules and going through the tutorials taught me how to do everything. The only problem I had was why do I want to do something. It takes a little playing of the game to realize the paths to take to fulfill the victory conditions. Sounds like if victory is achieved by occupying strategic locations and the Royalists win a strategic tie, the onus of offensive action is on the Parliamentarians.