On the heels of reviewing my now-favorite Vladimír Suchý game, Evacuation (2023, Delicious Games), I decided to rip the shrink off the other Suchý game I picked up at SPIEL last year, Shipyard (2nd Edition). (I’ve been excited about this one for a while now.)

Shipyard is a dinosaur to a modern gamer, as it was first released in 2009. To some of my friends, the original game is a classic, but those friends have never been kind enough to introduce me. When I had the chance to grab the updated version, I jumped because I needed to know—does the original still work, fifteen years later?

The answer? It depends on how long you can stomach the wait to score points.

Ahh, the 1870s

Shipyard is a 1-4 player rondel and tile drafting game that situates players as shipbuilders in the 1870s. Over a series of rounds, players will take turns until a countdown timer expires, giving each player one final turn to finish building ships and send them on a test voyage—known as a “shakedown cruise”—to impress local officials.

Each turn after the first turn of the game looks the same. Each player has a cube (or cubes, in a two-player game) on one of the action tiles that sit in an action selection area. The active player will remove their cube from the action tile they selected on their last turn, move that action tile to the front of the line—which triggers a slight movement of a gear that is used for the game’s timer—then select a new action for the current turn that is different from their previous turn. This new action must also be unoccupied by other player cubes.

Before or after their main action, players can spend six guilders (money) to take a bonus action, an action that must be different from their main action. For each player with a cube ahead of the active player’s newly-placed cube, they get one guilder, so there’s an incentive to select actions behind other players to gather a bit of cash.

About half of the game’s action choices include paying for ship parts, commodities, and canal space that will be used for those shakedown cruises. We found that the other half of the game’s actions were much more interesting, if only because of the timing considerations based on the action wheel where these other actions reside.

On a separate board, there is a four-ring rondel. Three of these rings are used to select crew, ship components, and ongoing player powers (known as employees). One of the rings is a constantly-shifting market for commodity prices. Cubes are used in each ring to denote what items were most recently acquired, and if a player selects one of these four actions, the cube within that specific part of the ring moves one space clockwise to offer the active player a new choice.

For all of the rings except commodity prices—which can only move a max of one space per turn—a player can spend a guilder to move forward one space on the action wheel, and one additional guilder for each space they want to keep moving ahead, to get what they want for their ships.

Time has been kind to this mechanic, because this part of the game still works quite well.

The ship parts drafted throughout play are slowly assembled on each player’s personal board and are composed of various features that are mainly used to score points during a shakedown cruise or qualify ships to score end-game scoring milestones. The pieces representing the front of the ship (the bow), the middle ship sections, and the back of the ship (the stern) all have small features such as life buoys and cabin quarters that must be carefully aligned with the proper crew and components to make a successful voyage.

Each ship needs a captain. If you want to build the fastest possible ships, you’ll need both smokestacks and a stoker. Businessmen and soldiers are also happy to join the shakedown cruise, but they will only stay in specific crew quarters on your ship. Sails and smokestacks can only fit on certain color mounting areas of each ship. You get the idea.

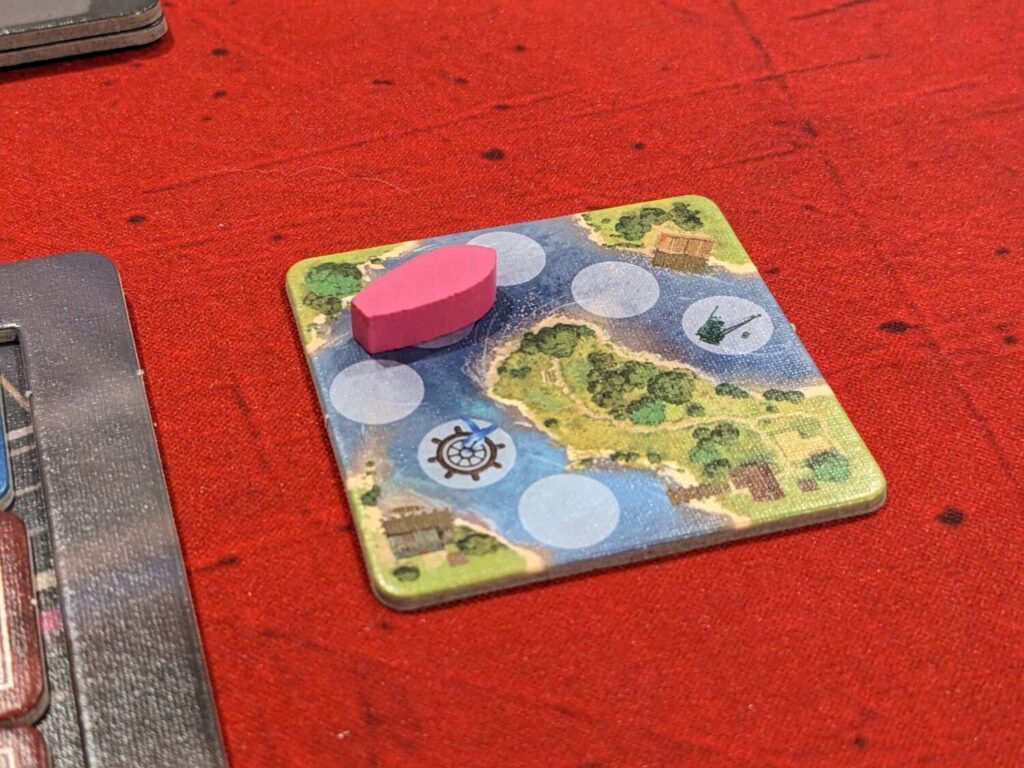

At the end of any turn where a player has completed a ship, that player must send it down a rented canal for a shakedown cruise, to show it off to various local officials. A comically small little wooden boat is placed on a tile showing a canal with spaces that trigger scoring for certain parts of each ship. Cross over those spots and you’ll score bonus points for matching ship features, along with points for crew members, the speed of the boat, and a few other extras.

In my experience, players push a small number of ships into canals to have them scored, anywhere from two large ships composed of 8-9 ship parts, to five or more smaller ships over the course of the game. Since the only in-game scoring comes from these ships, you are probably wondering the same thing I was wondering when I first read the rules:

How slow does this game start? My finding: really slow.

Patience is the Key

I thought that I was a pretty patient guy, at least before I began my review plays of Shipyard. Now I’m rethinking that, because it would sometimes take a number of turns before anyone scored for their first ship.

There are many reasons for that, and I’m sure this is partially due to my desire to have all the things I can to make my ships extra fancy. On the first turn of the game, you won’t have all the things you need to even attempt a shakedown cruise: a captain, three or more ship parts, and a canal.

But then complications arise, as you try to min-max the operation. Employees grant ongoing powers that make better use of common actions. A recruiter allows a player to get an extra crew member when they are already getting crew members…shouldn’t I wait to get one of those recruiters before taking the hire crew action? Traders make commodity actions better, so maybe I’ll wait to do my first commodities trade until I have a trader!

I’d like to take a certain action, but if I take a different action farthest to the left right now, I could take a less optimal action but get three extra guilders for the three players behind me…what should I do?

The first 30 minutes of each game was composed entirely of these moments. No one squeezes a ship out too quickly. Scoring comes in waves, with final scores that ranged from the low 50s to the mid 70s.

And usually, no matter what I told players during the setup, players always want to do the same thing: build the sweetest-looking boat in the Realm. Maximum crew. All the fixins, in the form of ship features. A boat with a stoker and a few smokestacks to max out the ship’s speed.

And that takes most of the game to do. I don’t think of that as good or bad, actually…it just leads to a game that is mostly quiet, suddenly interesting, then quiet again for stretches at a time.

The interaction in the action selection area is fantastic, though. Just when I wanted to hire crew, the player in front of me took that action, blocking it for my cube placement on my turn. Sure, I could spend six guilders to take that blocked action as a bonus action, but I needed that money to go shopping for parts…

That Ship Has Sailed

Shipyard is a tricky one.

I had fun with it, and everyone who joined me for plays also enjoyed their experience. However, all of these players admitted that they were not likely going to suggest playing Shipyard again.

That’s not because of a dense rules overhead. In fact, the well-written rulebook led to a teach that only takes about 15 minutes. The only consistent question from players came with how the end of games play out. Shipyard is like the “long kiss goodnight” ending from films like the third The Lord of the Rings film—there’s a final normal round, then a final turn (with no option to buy a bonus action), then a final chance to add a single part from the market to an almost-finished ship to then take one final shakedown cruise. The end of the game almost feels too flexible.

I think some players won’t come back to this because of the lack of “wow” moments.

The best parts about Shipyard come with the interaction via the action selection tiles and the four-ring rondel. The rondel in Shipyard is interesting and made for a few fun timing considerations during each game. Do I take that crane now, or hope that my neighbors will push the cube along that specific rondel action in another turn or two?

But even these moments lead to many instances of “Hmm, OK then.” The main tension I felt even during my third game was around the assembly of my ships, making sure to line up the pieces I needed with my end-game goals. I loved cursing other players from time to time when they snaked me on an action I wanted to take, but that again led to a pivot, not an outright “YOU DIRTY *&^%%$#@” assessment during play.

The only rule/mechanism my opponents agreed on as a negative: the rented canals just feel off. “Extraneous” (a word I don’t use often) came up twice after the multiplayer games. Wasting actions to grab those tiles just didn’t feel right, and the idea that each new ship enters in the middle of a canal also feels off. But the ships have to score somehow, and I guess this is the best way that could be done? I’m not sure, but grabbing canal tiles is the least enjoyable thing to do in Shipyard.

For those seeking an interesting puzzle with otherwise low levels of interaction, I think Shipyard would be a great pick at lower player counts. My four-player game of Shipyard took about three hours, including a teach; that’s too long for a game like this. I also tried Shipyard at three players (just over two hours, with the teach) as well as the solo variant, although the solo game here is not the reason you should buy Shipyard. The solo doesn’t do a great job of simulating what other players might do, and it requires a ton of individual maintenance thanks to the random removal of tiles and a reshuffling mechanic that gets tiresome quickly.

One note about the production (the version I have is the basic/retail version, with cardboard chits instead of wooden parts for the ship components and crew). Once everything is assembled, including the player boards, tile storage for the ship parts, and the action tile board, Shipyard is strangely not able to fit everything into its box. Like, not even close. There’s a great storage solution for the chits, but it doesn’t allow the box top to firmly seal the package together. And that’s before trying to put the ship parts storage unit back in the box, either.

That means you have to rebuild these two contraptions, the chit storage and the ship parts storage unit, each time you play the game. That’s too bad, because setup time is otherwise quite brisk.

Give Shipyard a look at two, maybe three players, which keeps the playtime down and provides chances at interesting moments thanks to the rondel and action tile area. Like his other games, Suchý continues to draw me in and I continue to be a fan of his approach to medium-weight Euro designs.

Add Comment