At first, I was trepidatious about Sarkaar. The game was submitted by the publishers for a review. It was entirely unknown to me and the rest of the team. It doesn’t, as of this writing, even exist on BGG. We get a fair number of review requests for games nobody’s ever heard of. In many cases, most even, there’s a reason for that. You grow wary.

The theme and mechanics interested me, though. I love games about politics, and I love area control. I was also excited by the opportunity to play a medium-weight euro from Indian designers. The world of board games is so Euro- and America-centric.

Sometimes a shot in the dark is a bullseye.

Political Science

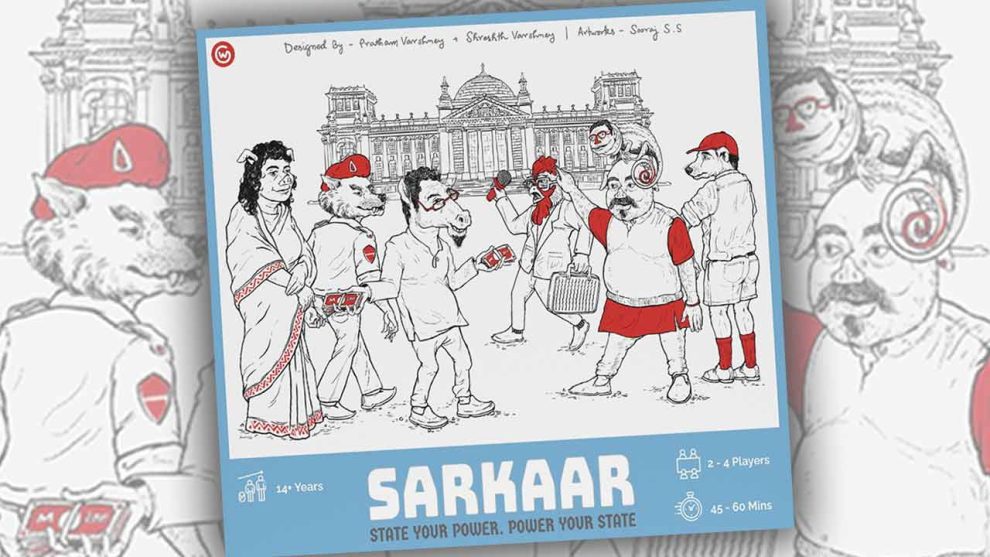

In Sarkaar, players take on the role of parliamentary candidates, each guiding their political party to supremacy by claiming seats in various states across India. This is done through a combination of campaigning, politicking, and good ol’ fashion corruption. The goal of the game is to end up with enough points, gained in large part by claiming majorities in different states, to surpass a player count–dependent point threshold. The first player to reach that number wins.

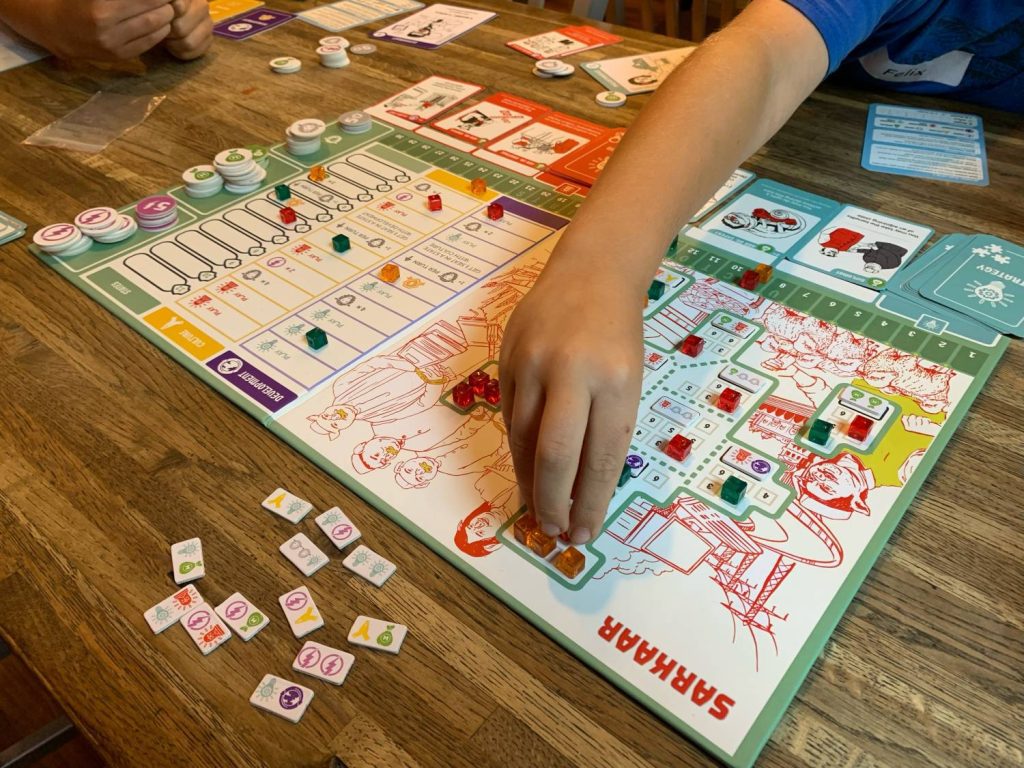

Every turn, you perform two actions, chosen from a pool of five (you can repeat the same action). Most of the time, you’ll be using one of the two actions that let you claim a seat in parliament. One lets you claim an empty seat, while the other lets you steal a seat from one of your opponents. In addition to the states, there are three tracks. One keeps a running tab of how many states you have presence in. The other two, the Development and Culture tracks, are rife with bonuses, be they voters or Moolah (money) or, most frequently, the ability to play a card from one of the two card markets. The tracks are the other primary scoring avenue: the player farthest up each of them receives 4 points.

The cards in the market come from one of two decks. The Aggression and Strategy cards feature powerful abilities when executed at the right time, or when executed in the right combinations. They give the game some spice.

Political Theatre

Any time you form a majority—more than half the seats—in a state, you score points equal to the total number of seats in that state. These are immediately added to your score on the tracker at the bottom of the board. The same is true of the points scored from tracks.

Don’t get complacent, though. Points are seldom safe in Sarkaar. If another player removes you from one of your seats and you no longer have a majority, you lose those points. If someone passes you on one of the three tracks, they take the 4 points away from you. Your score is immediately lowered.

You can see how this starts to get dramatic. Let’s say you control three seats in a state with five total, and one of your opponents controls the other two. The state belongs to you, but only just. If that opponent uses the Power action on their turn to muscle you out of one seat, you lose 5 points and they gain 5 points.

There is a constant tension in Sarkaar of having to choose between shoring up the strong positions you already have and expanding into other territories to try and reach that critical mass of points. There’s also the constant need to keep your opponents in check, even if it doesn’t immediately benefit you. Players slingshot up and down the score track. The current leader may not stay that way for long if they aren’t careful.

Some Combos Are More Equal Than Others

Sarkaar is a game of combos. The tracks have bonuses and the states have randomized bonus tiles that activate every time you gain a seat with the State action. The difference between winning and losing can be finding a path that squeezes one extra bit of bonus juice from the lemon of your turn.

Most of those state bonus tiles do two things. Some do three. If any of them involve tracks, you may want to bring a ball of twine to help make your way back through the labyrinth of your turn. It is extremely easy to get lost as to where, exactly, you are in the process.

“Wait. Was I picking that card up because of the state bonus, or because of the track bonus?”

“Oh I thought you were picking it up because the first state bonus let you play that other card that moved you up the track.”

“Oh…right.”

That’s my main criticism of the game. Possibly my only one. I’ve now played or led around a dozen games of Sarkaar, and I still get lost during a good third of the turns. There is something fundamentally inelegant going on here.

Two Cubes Good, Four Cubes Better

Sarkaar is a biting satire of Indian politics. The artwork, showing politicians as pig-nosed people and voters as full-on sheep, is inspired by George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The satire itself is pretty straightforward. “I think politicians might be corrupt.” Mightn’t they just!

What’s impressive is the extent to which the satire is incorporated into the mechanics. The Moolah is represented by Scrooge McDuck–style money bags and can be exchanged any time for more voters or power. The Celebrity, one of the candidates, gains extra voters at the beginning of every turn. The Legislator, a candidate whose hands are firmly on the levers of power, can choose to take a card from the market in lieu of the standard three voters at the start of each turn.

For such an abstract presentation, Sarkaar is remarkably evocative of the theme.

Windmill or No Windmill

The randomized state bonus tiles have a significant impact on what kind of game everybody plays. You have more avenues for choice than you’d expect. They suggest paths more than they dictate them. Cards that seemed useless on my first play have proven their value. At first, the asymmetric candidates don’t seem to make all that much of a difference, but after three or four games you see the ways they encourage you to play.

There is significant strategic variety. I’ve played games where I focused on one track. I’ve played games where I spread out as much as possible, and mostly prevented other players from keeping majorities until I saw an opening to take enough points to win. I’ve played games where I concentrate on complete control of a small handful of states. They’re all valid approaches.

In short, this game gets better the more I play it.

There Are a Few Provisos

Given that there’s a card market, there is some luck. When players are given the opportunity to take a card, they can also choose to go for the top card of the deck, so there isn’t quite perfect information. If that’s make-or-break for you in an area control game, you’ve been warned.

The manual is abysmal. I sent the designer an email with a large number of clarifying questions after the first game or two. Certain things, like the fact that cards can only be played on your turn or that you lose points when you lose control of a region, make a big difference and are never explicitly stated. This is a huge problem, and I hope they design a new manual for the next print run.

Teaching it can be tricky at first. First games will also be a bit slow, generally, unless you’re playing with people who have lots of gaming experience. Learning to see all the ways actions can ricochet takes a minute. That said, I’ve played a full game with three players in less than 50 minutes, teach included. Part of what makes it so good is that it is, ultimately, pretty snappy.

Final proviso: The game ends the moment one player makes it to the point threshold. This can make the end feel abrupt, and some people may not like that. I myself used to dislike first past the post victory conditions, but I’ve come to appreciate the way they emphasize that it’s about the experience of playing rather than the result.

In Conclusion

You will almost certainly never get a chance to play Sarkaar unless you order it for yourself. If you are interested, you can find it online. We don’t normally link to games like this, but Sarkaar effectively doesn’t exist within the internet circles where the Meeple Mountain audience tends to roam.

This is a fantastic design. It’s quick, it’s thoughtful, there are a variety of ways to play, and there’s plenty of drama packed in the back-and-forth scoring. Sarkaar deserves, with a significantly improved manual, to have much more of a public profile than it likely ever will.

Bring more new voices into board games. We’ll be all the better for it.

Add Comment