You awaken to darkness, an abyss so deep that the flickering light of your candle can barely illuminate the grey walls next to you. Inhuman screeches echo somewhere in the infinite night. With shaking hands you begin to move along the wall, hoping to find a friend…or better yet, a way out of here.

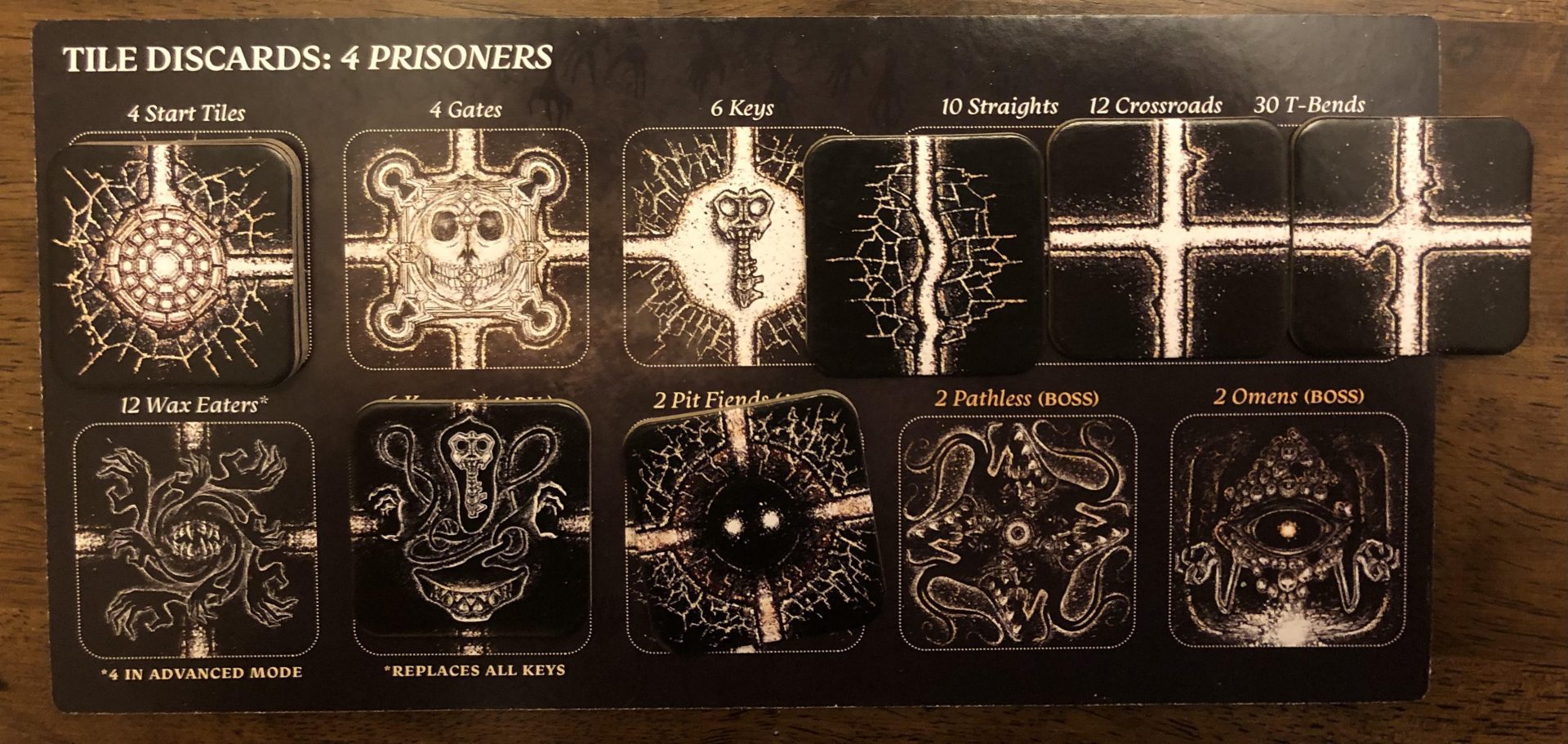

In this tile-laying horror game, up to 5 players take charge of characters trapped in a mysterious labyrinth. The players must place each new tile carefully to avoid the monsters lurking just out of sight, gather the required Keys, and collectively reach the Gate to win.

Night Moves

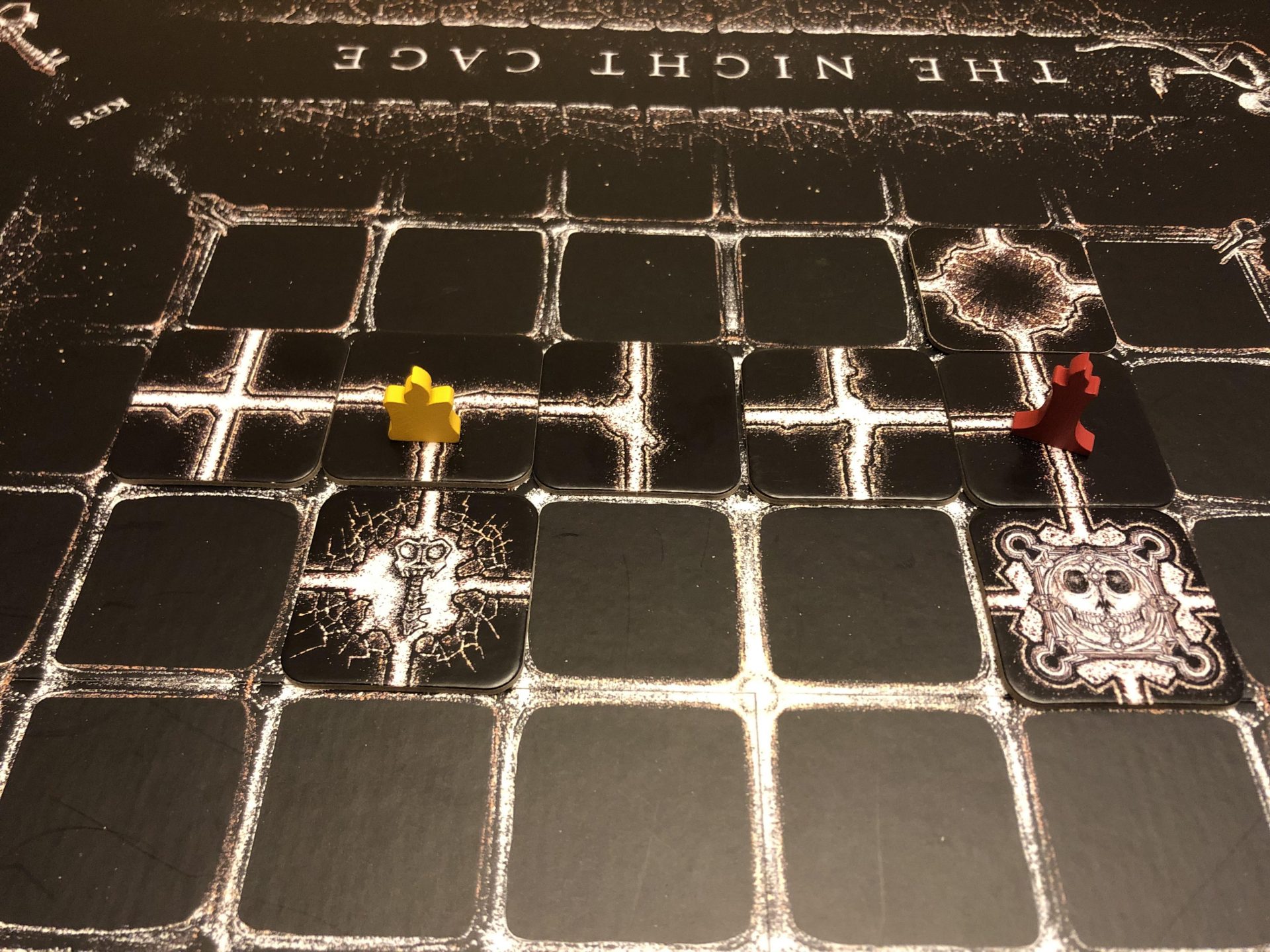

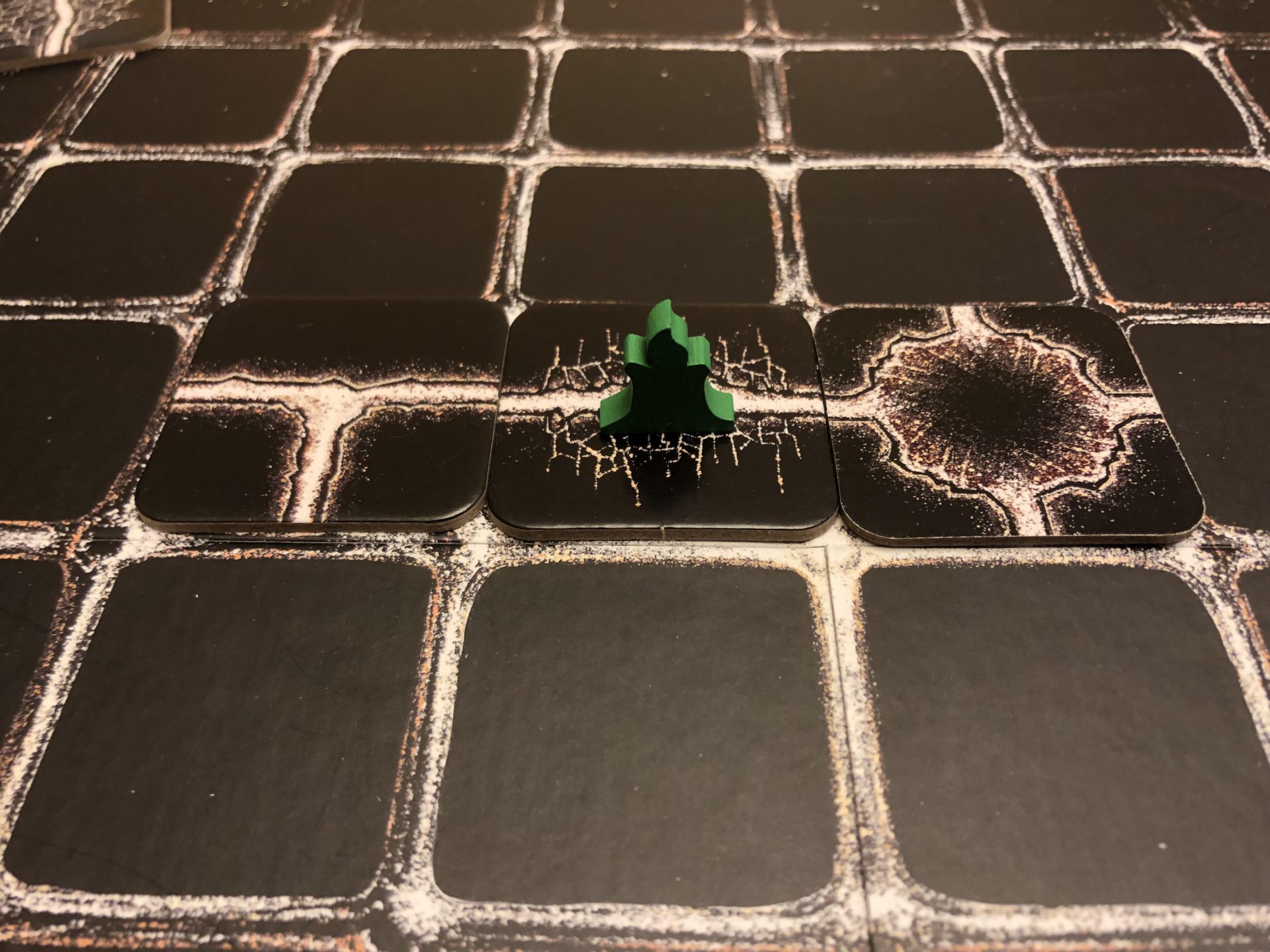

A game of The Night Cage begins with each of the 4 Prisoners, indicated by variously colored candle meeples, placed anywhere on the game’s 6×6 board. (Note that the 5-player game has 5 characters and uses a larger 7×7 board.) Each character is armed only with a candle. This candle enables them to see their current tile as well as each orthogonally adjacent tile. The first few tiles placed in this way will be, broadly, safe — but that won’t be the case forever.

To escape the maze, each character must pick up a Key by finding and entering a Key tile. Each Prisoner can only hold one Key, but a player who’s already secured theirs can help other players track down the next. Once all characters are holding a Key, they must find one of the Gate tiles. These are the only tiles in the game that multiple characters can stand on simultaneously. The game ends in a victory if all 4 Key-carrying characters are standing on the same Gate tile. If the players run out of Key or Gate tiles to discover, the game ends in defeat.

On a player’s turn, they’ll move their Prisoner one space in any available direction, following the path lines on their current tile. Some tiles show only a straight line, while others have T-shaped junctions or 4-way intersections. Each time a character moves, the player rechecks their current visibility: tiles which are no longer orthogonally adjacent to any character are discarded, while spaces which have now come into view are filled with randomly drawn tiles. For each passageway extending from the newly occupied tile, a new tile is placed such that it extends the path. Players who’ve tried other tile-laying games like Tsuro or even Carcassonne will probably be at home.

Of course, this isn’t an ordinary labyrinth. One tricky aspect of The Night Cage is its non-realistic architecture. The edges of the board do not end visibility. Instead, a character’s line of sight “wraps” from one end of a row or column to its far end. Players can move in the same way, allowing them to quickly traverse along the edges of the board. It can be odd at first for a character to stand in one spot and place tiles at the far end of the board, but after a few minutes it starts to feel like second nature.

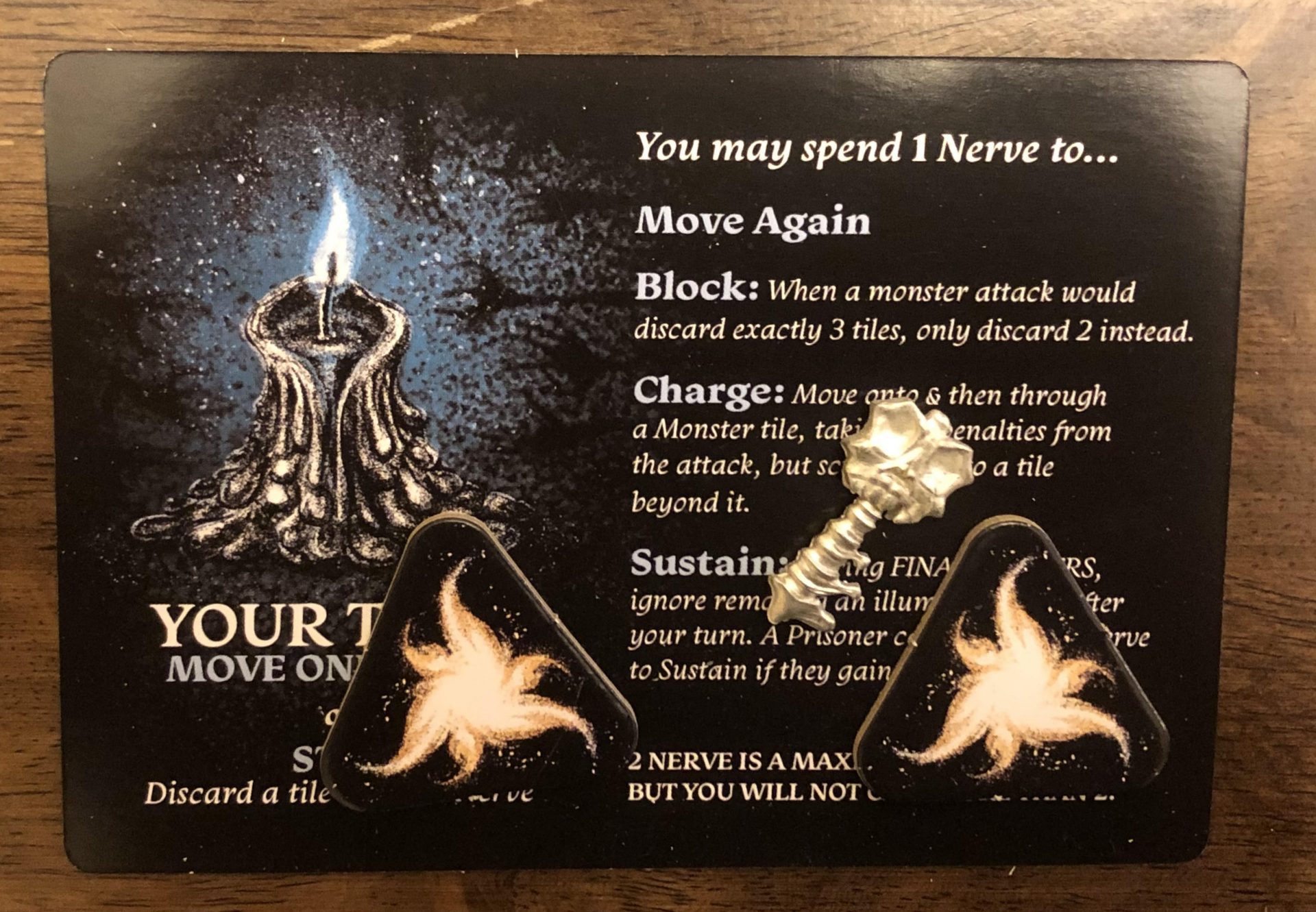

Players may also choose to stand still on their turn. However, some tiles are fragile, disintegrating as the character passes or even crumbling below their feet if they attempt to wait there. Treacherous pits form when a passageway collapses in this manner. A character who drops through the floor (for any reason) discovers another strange feature of this place’s surreal geometry. Their meeple is placed at the edge of either the row or column they fell from; at the start of their turn, they’ll “land” in an empty space along that line by drawing a new tile to occupy and then checking visibility as normal. Whether they fall or not, players who choose to wait on their turn gain a Nerve token which can be spent later for various effects, like taking a second move action on your current turn or resisting the effects of a monster attack.

Things That Go Bump In the Night

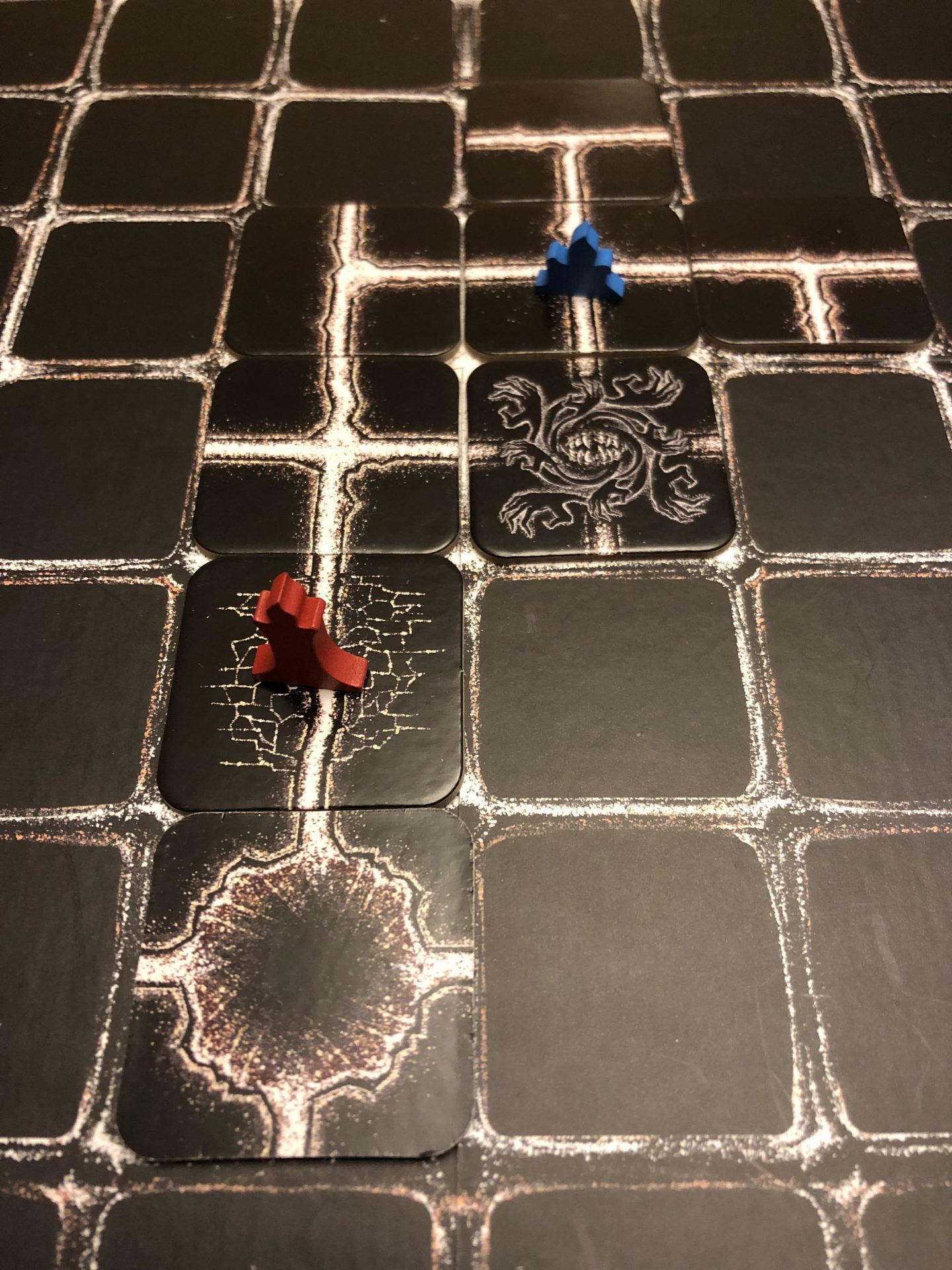

This labyrinth is more than a maze; it’s home to a variety of otherworldly creepies waiting to pounce. When a monster tile is drawn, its effect depends on the monster in question. The basic game features only Wax Eaters, which lay in wait until a character moves within their line of sight. Once triggered, they send an attack in all 4 directions, hitting anyone they can in a straight line. Worse, an attack that hits another Wax Eater will trigger another round of attacks, which can hit and trigger a third, etc. Only pits, empty spaces, and solid walls can evaporate a Wax Eater’s attack. Characters with no such protection take the full brunt of the creature’s effect. For each hit a character takes from a Wax Eater, they’ll have to discard 3 tiles from the top of the stack (or 2 if they’re willing to sacrifice a precious Nerve token). Multiple hits can create a cascade of lost tiles, running out the stack and potentially even eliminating all of the remaining Gate and/or Key tiles. If this happens, the characters are trapped forever.

There is no form of character damage in The Night Cage; even a dwindling health tracker would give players far too much comfort. In addition to losing tiles, Prisoners who suffer a monster attack go into a status called Lights Out. An extinguished candle is bad, but the panic that it causes in a character is worse. They immediately lose the ability to see any tiles adjacent to them unless another character can see that tile. On their turn, a Lights Out character must move; they cannot stand still unless they spend a Nerve token (which they cannot replenish until their candle is re-lit by another Prisoner). This combination — forced movement and an inability to see their surroundings — means that a Lights Out character is an unbelievable liability, revealing Keys and Gates before other players are in position to secure them or wandering willy-nilly into monsters.

The advanced game adds quite a bit of depth with multiple new types of monsters. Pit Fiends turn other tiles (including occupied ones) on the board into pits, which can be devastating. They pale in comparison to Keepers, who replace the core game’s Key tiles, and which must be defeated by moving onto them — usually at a great cost of tiles or Nerve tokens — in order to secure the Keys they carry. Even more advanced monsters include the Pathless and the Dirge, horrors that serve as boss monsters for experienced players only.

Caged Wisdom

The Night Cage has a lot going for it. It’s easy to learn and play, despite some rulebook layout issues that make it a touch difficult to reference rules quickly. And the production has some nice flourishes: the various candle meeples, the tower that holds the tiles, the delightful electronic candles, the sorting board that allows players to quickly gauge how close to defeat they are. The thematic elements are so clear that you know from the moment you sit down exactly what this game is about and what it’s going to do to you.

One thing I particularly appreciate about The Night Cage is that it’s well-suited to both multiplayer and solo play. There are always at least 4 wanderers, divided as evenly as possible among the players. In solo games, the player simply controls all 4. Because all the characters are identical, it’s a breeze to solo. In both modes it can occasionally be difficult to keep track of whose turn it is, as resolving a chain of effects can obscure the move that started it, but it’s still quite manageable on the whole.

Personally, while it might make the game a little more complicated, I do wish that the characters had something unique about them other than color. A single special ability for each character would go a long way towards helping the game feel more puzzly as well as more immersive. Or maybe the anonymity of the characters is the point — players are free to project their own fears onto the game’s lonely candle meeples and featureless grid.

The gameplay of The Night Cage bears that idea out. It’s a surprisingly abstract game: here the horror is born of anticipation of a bad draw rather than the sudden emergence of a truly grotesque nightmare. Even revealing a monster tile doesn’t feel particularly horrifying. It prompts a few moments of calculation as players figure out how to minimize the damage, turning “your worst fear” into something strictly mechanical, and then play proceeds.

That all changes when a player goes Lights Out. There’s a fair amount of randomness in The Night Cage, so players instinctively cling to what little control and foresight they have. To lose even that is to truly fall victim to the fear. In those moments, The Night Cage delivers on its central promise. The benighted character is suddenly and completely at the mercy of the next tile, forcing the entire table to rally around them lest they stagger into some fresh horror that will sink the team’s effort. Few plays are as satisfying — mechanically, narratively, and subjectively — as when one player braves crumbling pathways and lurking monsters to race across the board and rescue their terrified companion. It’s even better when that action fails, doomed from the start by unseen creatures or an untraversable wall.

All of which is to say that playing The Night Cage is an uneven experience. At its core, the game feels slightly too chaotic and too impersonal for a horror-style game. While I love the sense of danger it evokes, players don’t have quite enough agency or knowledge to steer the game in their favor. Time spent on careful positioning can feel wasted when all of the Key tiles are buried at the bottom of the stack. The choices that players make often boil down to hoping that the next tile isn’t somehow worse. And many of its puzzles don’t have a good solution: you simply take your lumps and cross your fingers that you don’t lose anything of value.

Mixed in, though, are moments of genuine dread as characters stumble into unexplored areas and trigger huge swaths of destruction. The relentless tick-tick-tick of discarded tiles begins to grate on the nerves as the possible number of Key or Gate tiles dwindles. It’s not until the situation really starts going south that the game begins to hum. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that I would gladly take a devastating, hopeless loss over an easy win or one where none of the players went Lights Out.

That might be a moot point. Wins, as it happens, are fairly rare: not impossible, but reasonably difficult to achieve. Even if there’s a lot of randomness, the difficulty feels well-calibrated in that regard. Players who are able to make smart decisions at the right time can maybe eke out a victory despite bad luck, while players who move too aggressively or too cautiously usually end up just a few tiles short in the game’s final moments. There are also quite a few options to tweak the difficulty by adding or removing certain tiles. For gamers who like what The Night Cage offers, there’s a fair amount of replayability here, and each game is quick enough that you could fit a few into an evening.

Unfortunately, that person isn’t me. I’ve enjoyed The Night Cage, but I’m afraid I don’t love it. I want to love it. There’s so much charm packed into this box and when it hits, it hits brilliantly. It just didn’t hit consistently enough for my tastes. If it seems like the kind of game you’d enjoy, I’d recommend trying it before buying. You might find, as I did, a decent game that doesn’t quite live up to the expectations it sets. Or maybe, just maybe, you’ll find yourself snared by The Night Cage’s infinite paths.

Dear Ian, at first 3 ganes, i have my doubts on it. Then it grows. What is absolutely necessary for us : Put the Pit fiends in the game. And with tiles…

We found it more thematic, if you choose first where you want to place the tile on the board then flip it over and lay it down there. You have only a candle. You can’t lit in all directions. You hold a candle in a passage way to see and then in the next.

We play this way and need 15 games, some very close to one tile, to win.

This is a great little game. And it is important, besides luck, that nobody makes mistakes.