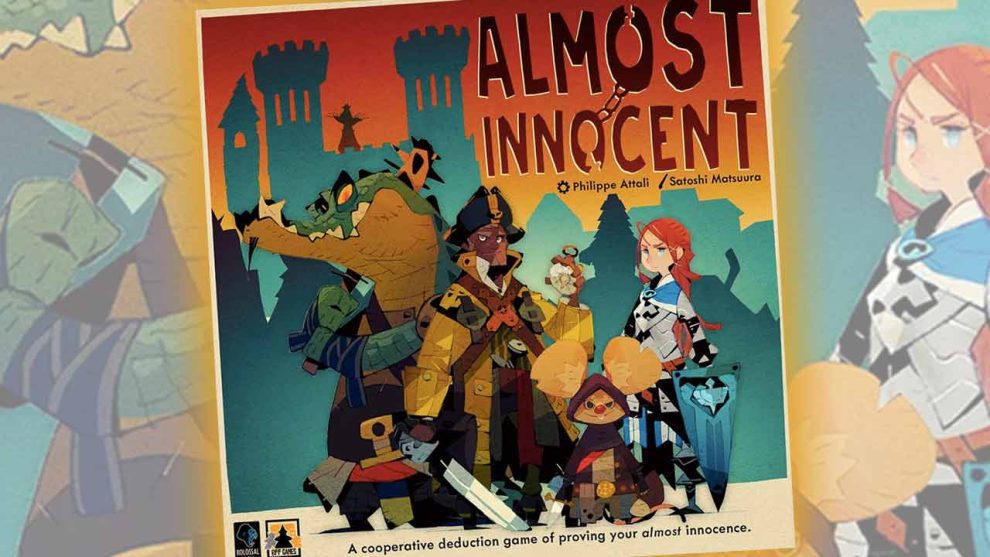

Kolossal Games (Reload) is heading to Kickstarter this month with a campaign-style cooperative deduction game titled Almost Innocent. In many ways, this preview is unlike anything you’ll ever see—including what you’ll find in the retail version of the game. Allow me to explain.

Legacy and campaign-style games that depend in any way upon story face a distinct challenge in this early preview stage because of potential spoilers. Kolossal has attempted to dig up this roadblock by issuing a prologue to media outlets. This preview covers three scenarios that exist independent of the game that will hit retail next year, so nothing you see here will spoil your experience.

Instead, the scenarios in the prologue offer a peek into the progression of game mechanics in a way that entices without laying all the cards on the table, so to speak.

For the prologue, players take up the role of pub-dwellers who find themselves trapped inside when the owner learns that someone inside has been harassing the town and causing trouble. In order to escape, each player must deduce a story capable of buying passage to the ground above suspicion—proving themselves almost innocent. Success comes only if everyone at the table solves their individual conundrum.

Scenario #1

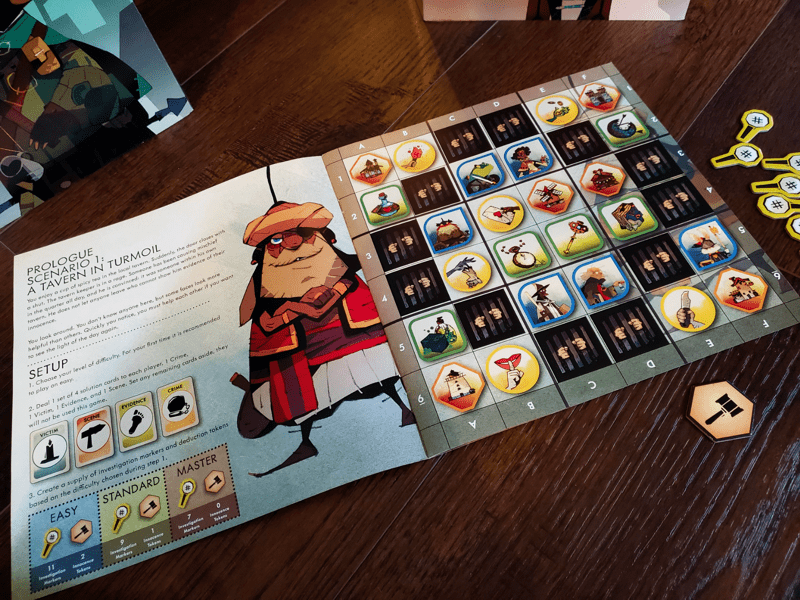

Almost Innocent takes place in a central book that serves as the board, not unlike Almanac: The Dragon Road, also from Kolossal. The game board is a six-by-six grid. In the first scenario, twenty-four of the squares depict images matching the game’s twenty-four starting cards. The final dozen squares are barred to indicate they will not figure in anyone’s solution.

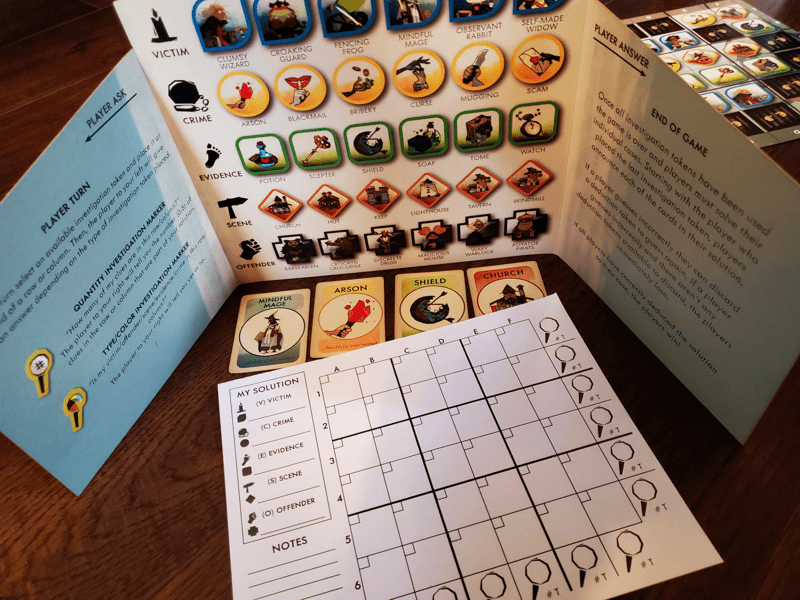

The cards are divided into four categories: Victims (blue), Crimes (yellow), Evidence (green), and Scenes (orange). Each category is shuffled, with one card then being dealt privately to each player. At the outset, each player is holding the solution sought by the player to their left.

Players also receive a shield and a tracking sheet for solving the conundrum. Before the game begins, everyone marks any of the barred coordinates on the board along with the solution on their neighbor’s cards—the sum total of known information.

Based on the chosen difficulty, players gain access to a number of Investigation tokens to place when making inquiries. Inquiries come via two questions: How many of my cards are located in column/row ____? or Is my [category] in column/row ____?

Players take turns asking questions. The active player receives an answer, then everyone at the table receives the answer to the same question. In this way, columns and rows and cards are laid bare with just the right amount of obscurity to keep things interesting. Play continues in this fashion until the Investigation tokens run out.

At the end of the scenario, players reveal their deduced answers one category at a time. If at any point a player is incorrect, they claim a token enabling them to try again, but there is almost no room for error. Easy, Standard, and Master allow for three, two, and one error, respectively.

If everyone at the table correctly identifies their corresponding Victim, Crime, Evidence, and Scene, they proclaim a collective victory and move on to Scenario #2.

Scenario #2

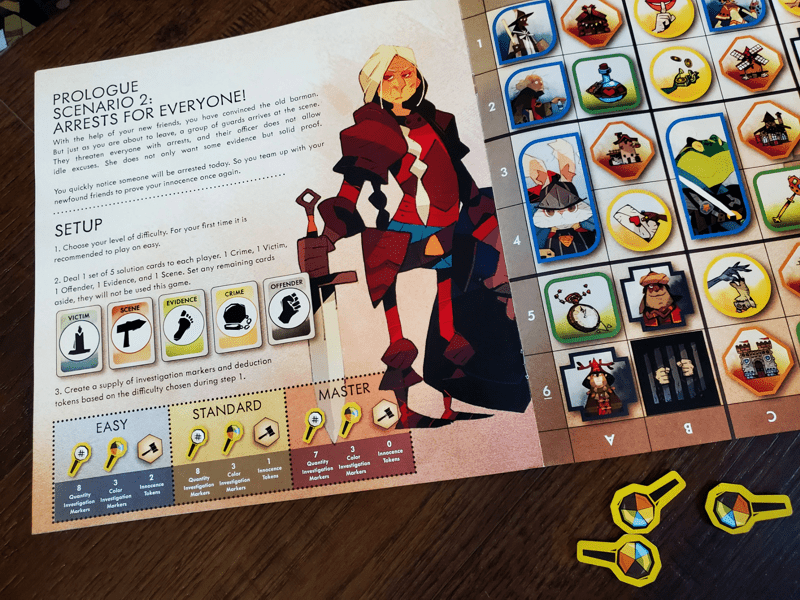

Scenario 2 keeps the setup and gameplay intact with three significant changes. First, a fifth card category—Offender (black)—is added to the mix, meaning every player must now decipher a set of five cards in order to achieve success. This additional card set also means there are fewer barred spaces on the game board to allow for the new images.

In addition, a few of the category images now span two squares on the grid. Asking whether your Victim is in row 4 might yield a yes. However, the same can now be said of row 3 as well, opening the door to potential confusion.

Finally, the Investigation tokens, which had previously been available as either Number or Category inquiries, are now restricted to a specific number of each type. The restriction swells the need for a keen sense of timing.

Scenario #3

Scenario #3 dials up the action even further through the addition of the Mischievous Mouse. The Mouse, who also happens to be one of the potential Offenders, is something of a metaphorical rat, interfering with players’ attempts to pin the trouble on someone else. The Mouse token moves about the board according to the movement of a die, blocking rows and columns from questioning. In a game where timing can take on supreme importance, losing a potentially consequential inquiry forces extra creativity for sure!

Impressions

Almost Innocent is a refreshing exercise in genuine cooperation.

Because every player at the table will receive the answer to every question, every turn is pregnant with opportunity—both for success and failure. Players investigate not only to find information, but to give information to their neighbor as well. Sometimes asking a so-so question for yourself means making a top-notch revelation to someone else, creating a counter-intuitive but remarkably satisfying moment for the table.

In one of our two-player games, my daughter asked a question that was borderline unhelpful on her own tracker, just so she could tell me that three of my cards were in a specific column. With only eleven questions at our disposal, it was a sacrifice. But it was a sacrifice that paid massive dividends as I was quickly set free to ask helpful questions in return on our way to victory. I love that the give and take is, well, give and take.

Conversation is limited to the questions around the table, meaning this is a cooperative endeavor where everyone must be on their toes for every question asked. Where so many cooperative games open the door for a strong player to quarterback the experience, that is just not the case here. Almost Innocent invites every player’s attention and participation, to the blessing or curse of the whole crew!

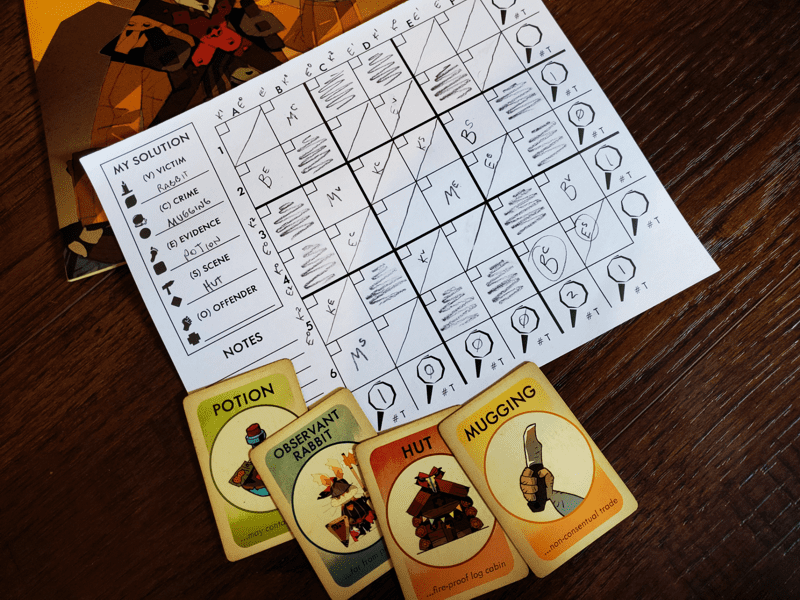

In another play, my wife had figured out several cards in each other player’s solution while solving her own. Depending on the level of note-taking and thoughtful consideration among the crew at the table, folks who are eager can aim for far more than even the game asks.

The layered reveals at the end open a last-ditch chance for success. As each correct card comes to light, players can keep their nose to the grindstone on the tracker, marking squares and eliminating possibilities that just might unlock the last logical steps to victory. I can recall one game where I had two possible Victims at the game’s end. I guessed wrong. But the wrong guess cemented every other answer on my sheet and we still won with only the one hiccup. The nervousness of the moment stuck with me, though.

The taste of artwork provided in the prototype is simply fantastic. Satoshi Matsuura’s distinct artistic style provides a charming collection of characters and places to lend a little life to the pub. I am excited to see the finished product, if only to see the fullness that is teased here.

Any uncertainty I have at this point in the production revolves around the narrative driving Almost Innocent. I struggle to connect the dots between story and mechanics. Somehow in this pub setting, my friends each know a story that would help someone, but not themselves. With a curious bartender breathing down our necks, we’re all driven to hint at these stories—by pointing fingers around the room, I suppose—so that someone else can pin the crime on someone else while we’re trying to do the same? My head spins thinking about it from any realistic perspective.

But here’s the thing about the story. This is the prologue. This was a one-time story, a sidebar produced to help you see the potential. Assuming the game is funded, the real story will come to light sometime next year. I’ll be just as surprised as you.

On the family side, it’s worth noting that while our nine-year-old was all in for the first Scenario, he was less capable in each of the next two. As the game progresses and every clue requires full attention and the occasional connection of less-than-obvious dots, the game might pass by the young despite the inviting artwork that turns their heads. The game doesn’t afford the chance to talk openly through the logic over the board, making parent-child team-ups challenging. I have to believe he’ll be more ready by the time the game comes to retail. The tweens, teens, and adults, on the other hand, were all-in from the beginning and quite intrigued by the Investigations.

This much I can say: Almost Innocent is a delightful play that is chock full of nail-biting tension. The gameplay is rhythmic and grows at a manageable pace. The endgame reveals are entertaining—especially in shared victory. I hope the final production narrative follows suit, even though it seems destined to take a backseat as a vehicle to introduce subtle changes to the board and the mechanics. I could be wrong, but I’m not even sure it matters all that much. The interactivity and ingenuity of the puzzle might just be enough for a solid experience.

If you’re into gridded logic puzzles where one square has the potential to unlock a sequence of interconnected revelations, you’ll likely dig Almost Innocent. Though it is only vaguely connected, I can’t help but think fans of Sudoku will love this one. I have a feeling the finished box will serve up a series of fascinating plays, heartbreaking losses, and deeply satisfying victories.

If you are interested, check out the Kickstarter for Almost Innocent.

Add Comment