I wonder what the per-capita murder rate within board games comes out to. If you’re an identifiable character, are you more or less likely to meet a gruesome end than the real-world distribution would suggest?

A quick google tells me the odds of getting murdered in the United States are around 1 in 175 or so, while international statistics are about 6.5 in every 100,000 (And I’m proooud to be an Amer-i-can). There are 2,075 board games on BGG with Murder/Mystery as a category, most of which are going to have a higher murder count than one per game. Finding the total number of games on BGG is difficult, but three years ago, the number was at about 125,000, so, assuming a rate of 3,500 games a year since then (slightly high to accommodate for old titles being added), we’re looking at a 1 in 65 chance of being in a game about murder. It’d be harder to bore down any deeper into these numbers without doing a lot of work I do not feel like doing.

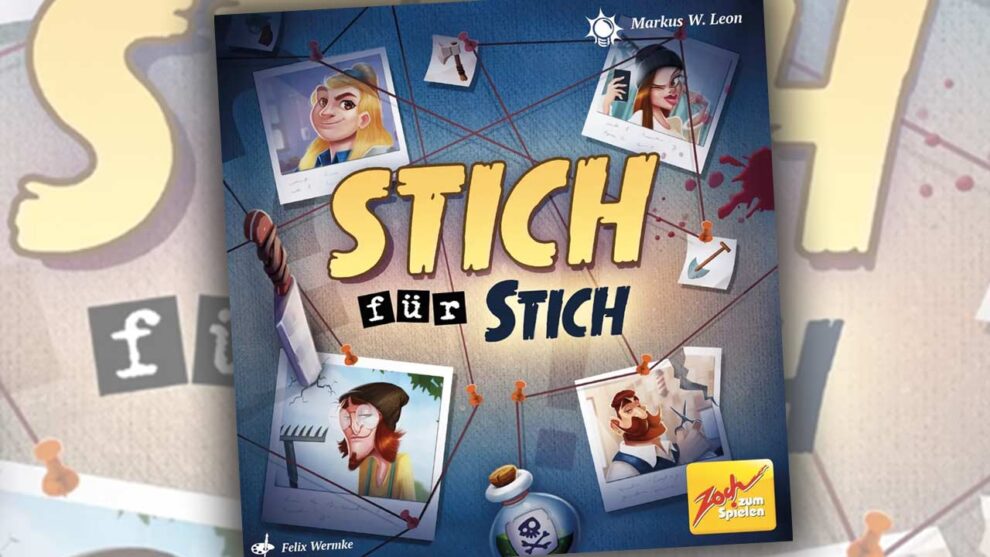

All I mean to say is, there’s a lot of murder out there. Add Stich für Stich to the pile.

Trick Me Up

Stich für Stich marries trick-taking to deduction. Each player spends one round as the confidant, who knows the murderer and the weapon. Everyone else is in the dark. The deck is full of numbered cards showing a combination of the four murder suspects and the seven murder weapons. Each trick is an exercise in deduction.

How does that work, exactly? How can a trick tell you anything? If nothing else, Stich für Stich deserves credit for being a very clever design. The game operates on a nesting series of trump suits. A card with both the correct murderer and the correct weapon will win the trick. In the likely event that such a card is absent, the highest numbered card showing the correct murder weapon wins. If nobody has the right murder weapon, the murderer takes precedent. If neither is correct on any card, the highest card wins.

It takes a minute to get fully comfortable with navigating the ladder of trumps, but comfortable you get, and the deduction settles pretty quickly into the realm of the intuitive. It helps that each player is given a stand and eleven cardboard tokens. I fell into the habit of tilting eliminated suspects and weapons to the side, as my own form of note keeping.

After each trick, the unknowing players pick a weapon and a suspect, passing them to the confidant, who says only whether or not the guess is correct. No information as to what is or isn’t right is passed on. The guessing players score points according to how early in the round they get it right. The confidant scores points for how long it takes, and the longer the better. Never is best.

Crisis of Confidant

As the confidant, you have a bigger hand, giving you a little more freedom with how to play your cards. Everyone wins points for the tricks they win, but it can be in the confidant’s interest to surrender tricks, muddying the deductive waters with cards that mix up the signals everyone else is picking up. This is an electrifying idea, but it doesn’t play out that way. From time to time, an opportunity to do something interesting appears, but it vanishes as quickly as it arrives.

That’s not to say the game is bad! It isn’t. Stich für Stich is fun. It never manages to pop, though. You’re not going to walk away craving more. Still, it’s trying something new, and I find that entirely worthwhile.

To me, Stich für Stich is a curio, a brave advanced team heading out into the unknown lands of marrying deduction with trick-taking. There is, I believe, a great game in this marriage, even if Stich für Stich isn’t it. This is a game that will stay in my collection, tucked in the back of the trick-taking section, waiting for me to pull it out to show my friends who design games. I would love if it were more than that, but it isn’t quite. This is a particular sort of gamer’s game, a game for people who love the design of games, who love the ideas even if the reality doesn’t quite match that potential.

Add Comment