I’ve really scaled up the difficulty level in my 18xx journey this year. After treading water with some of the classics, such as 1830: Railways and Robber Barons, 1846: The Race for the Midwest, Shikoku 1889 and 18Chesapeake, I have begun to seek out more complex iterations of the classic system started with 1829, designed by Francis Tresham about 40 years ago.

As a part of this second-level exploration, our friends at GMT Games were kind enough to send me a copy of 1848: Australia (first published in 2007 by Double-O Games, then in 2021 by GMT). 1848, designed by Helmut Ohley and Leonhard “Lonny” Orgler, is set around the railway business of Australia at the start of the country’s railway business. This business was initially a horse-drawn railway in the 1830s before it became a more industrialized system, moving not just people but mining, logging, and cement factory goods. The Sydney Railway Company, the first of the big railways in Australia, began operations in 1848.

1848 shares many of the systems started in 1829 and prevalent in most of the 18xx games I’ve tried so far. If you want to learn more about how the basics work in these games, please take a look at my previous coverage. We’ll talk here about ways that 1848 differs from other games in the canon…but, spoiler alert, 1848 is really interesting and particularly stabby.

Chicken Tasted the Same Back in 1848

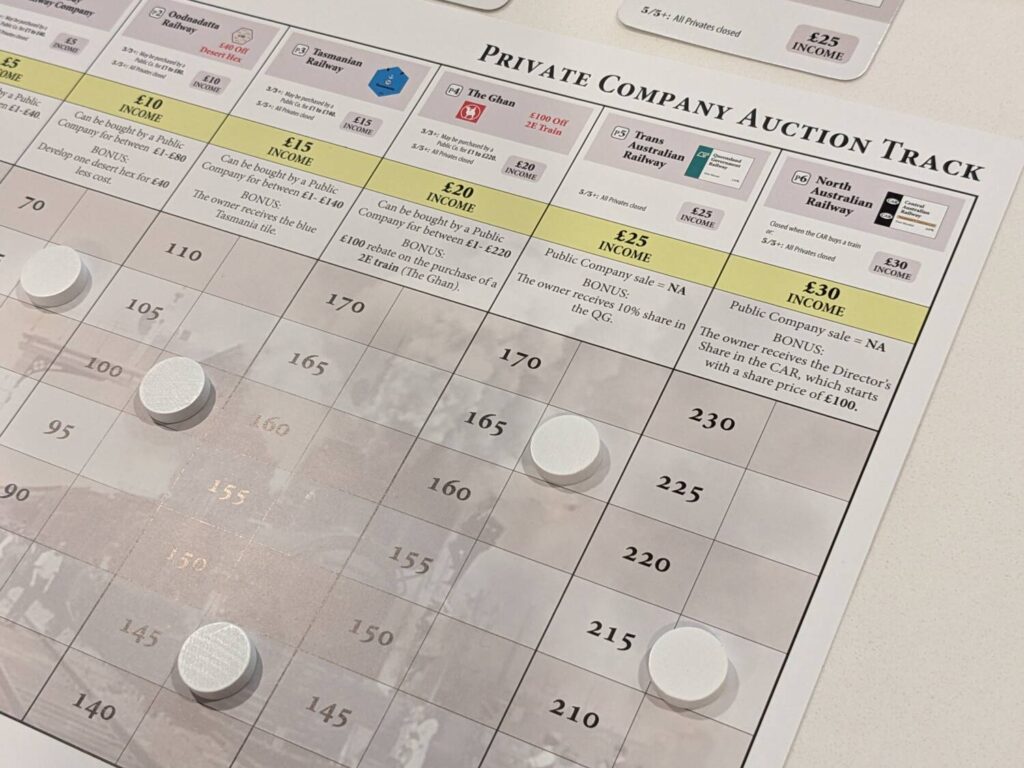

The first major change with 1848 versus other 18xx games that feature private companies comes during the initial private company draft.

A separate board, the Private Company Auction Track, shows the six privates featured in 1848 as well as a price track with values in descending order. For example, one of the privates, The Ghan (a special 2+ train that can only travel to Alice Springs, a location in the northwest corner of the map) has a starting auction price of £170. Players could choose to buy The Ghan for its current auction price, or reduce that price by £5.

Once a private’s price has been reduced seven times, it hits its minimum price level. At that point, a player that hasn’t already bought a private must buy something, or reduce another private to its minimum price. If all the privates are at the minimum, a player has to buy something! If all players pass and all players have at least one private, all of the previously purchased privates pay out their income, then this process continues until the privates are all in player hands.

In each of my plays, I think this is the “worst” part of 1848. It’s not necessarily bad, but it is usually predictable (now that I have ten plays under my belt, mostly through online play at 18xx.games). In essence, the private auction is a massive game of chicken. Who wants to buy anything at full price? No one. There are certainly sweet spot moments to buy, particularly for the director’s share of CAR, the North Australian Railway; around the £215 price point, jumping in feels like the right move.

I’m also not sure that privates have that much of an effect in this game. Take, for instance, the Oodnadatta Railway. Great private if you can buy it at the minimum, because then you’ve paid only £40 and you are getting a £10 income every operating round (or “OR”) and you get a free yellow tile placement on a desert hex. Situationally interesting, but usually not enough to buy this one for anything near its opening price.

The other big thing: across my ten plays, I have won twice and finished a very close second (less than £100) twice. In those four games, I either didn’t buy any privates or bought one because I was forced to. In other words, I am finding that I’m more competitive when I begin play with my full allotment of starting cash (£630 in a four-player game, £510 in a five-player game, £430 in a six-player game) to start a corporation.

I don’t love the private draft here. Thankfully, I adore everything else in 1848.

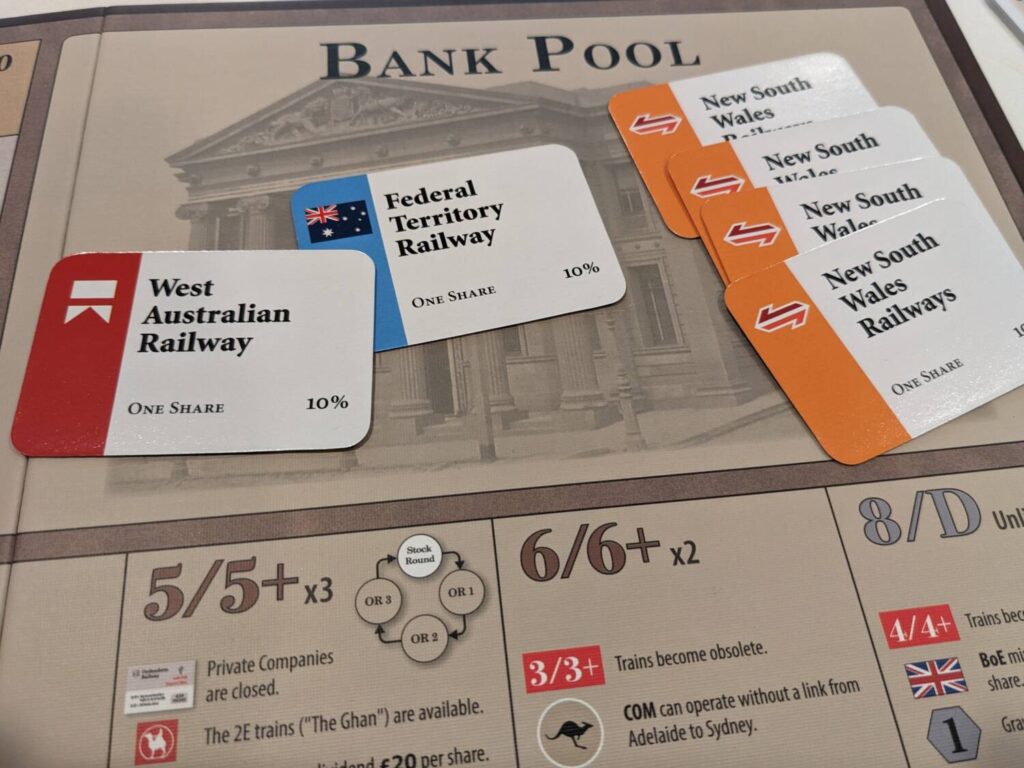

COM On Over to the Bank of England

There are eight public companies in 1848; seven of those are available to operate as soon as 60% of their shares have been sold. 1848 is a “full capitalization” game, meaning that when 60% of shares are owned by players, the corporation receives its full capital based on its initial share price times 10. So, a company with a par/strike/initial share price of £100 per share gets £1000 when that 60% threshold is achieved, and that’s all of the funding they will get for the entire game.

The eighth company is different, though. Commonwealth Railways (COM) still funds the way other corporations do; when 60% of its shares are owned, it receives all of its funding based on its par price. But there’s a second condition: a notional train of “infinite length” must be able to travel from Sydney to Adelaide with existing track. (Stations of other corporations can’t block this imaginary train.) If these conditions don’t happen by the time the first 6/6+ train is purchased, COM can start operating like a normal corporation.

COM also gets two starting stations: one in Sydney and one in Adelaide, even if there is no room for tokens on those hexes. It’s a very, very powerful operation, one that has the best chance of running long diesel routes late in the game if a crafty player has built out the routes and other players have not built other stations to gum up COM’s chances.

COM is wild, and I’ve seen players really swing a game of 1848 based on when they jump in to begin funding it (since no one will fund COM when play begins). I’ve also seen players badly misunderstand when COM can begin operating. In these cases, players might sink a couple hundred pounds into starting COM then realize during ORs that track won’t exist in time to make the Sydney-to-Adelaide connection. This can be critical—that seed money in COM is then frozen, and not making money on your investment is a killer in 18xx games.

The other big operational change in 1848 versus other 18xx games I’ve tried: the Bank of England. A second board tracks the Bank of England (BoE), and all of the things BoE can do change the game. First, players can buy shares in BoE, at a starting price of £70. The pool of BoE shares is ten. This BoE share price goes up all game long, in increments based on the number of loans other corporations take during play (each corporation can take a max of one loan at £100 on each of its ORs).

The BoE becomes really sexy when corporations begin to go under. In 1848, running a bad company has dire consequences. If a company ever needs to buy a train but can’t do it (after that company has taken a loan), the company goes into receivership, and for every loan it needed before going under, BoE’s share price moves one space to the right. And BoE pays fixed dividends—nothing during the yellow track phase, £100 (so, £10 per share) during the green phase, etc. But when a company goes into receivership, the fixed revenues then add the value of each city marker where the old company used to have a station.

I’ve played games of 1848 where BoE was paying out £600 or even £700 each OR in fixed revenues. For savvy players who invest in BoE right before other corporations start to take loans, that can be a major payday.

“If my company is failing, why would I take loans? It’s just going to go under, then I’ll get paid out for the shares and move along.” Nope, not in 1848! A player’s certificate limit is dropped by two for the director of a failed corporation…and, 18xx vets will tell you that less shares usually means less money. Less money is bad! Also, the director is the one on the hook to personally pay out other players for their shares in the failed company, if that company’s treasury didn’t have enough cash to cover everyone.

1848 has proved to be brutal at times. And that’s before your neighbor dumps their company on you.

Rusty Shiv

18xx games have a reputation of sometimes being mean, at least in the way that is mean if you didn’t know what you were getting into a phone booth with a mass murderer on the run. “Mean” usually happens when a player buys more shares than a current director, leading to a “hostile” takeover of a company, or when a director who is running a poor company decides to sell the majority of their holdings to the market, leaving a different player as the new president of a terrible company.

I’m surprised how often this behavior happens in 1848. In all but one of my plays, someone dumped their company on another player.

Some of this is forced because players don’t have enough money after the private company draft. If you only have £300, you cannot start your own major corporation on your own, because the lowest par price for a new corporation is £70 (meaning £420 is needed to start a new corporation). That forces tenuous alliances with a player who can kick off a new company. I’ve played a handful of 1848 games now where only two or three corporations are in business at the start of play.

If a director decides to dump five of their six shares into the market, that might leave another player who has two shares in that same company as the new director…and sometimes, that old director spent all of the money in the treasury. 1848 can be quite nasty; in fact, in one of my games, someone did that to me in the second OR after buying four 2+ and 3+ trains then building a train route for Victorian Railway (VR) that ran in a circle. It was clear the player did this to eliminate me from play. I rage quit that matchup and cursed that player in the online chat tool to ensure everyone knew how ridiculous it was to take such an action early in a game.

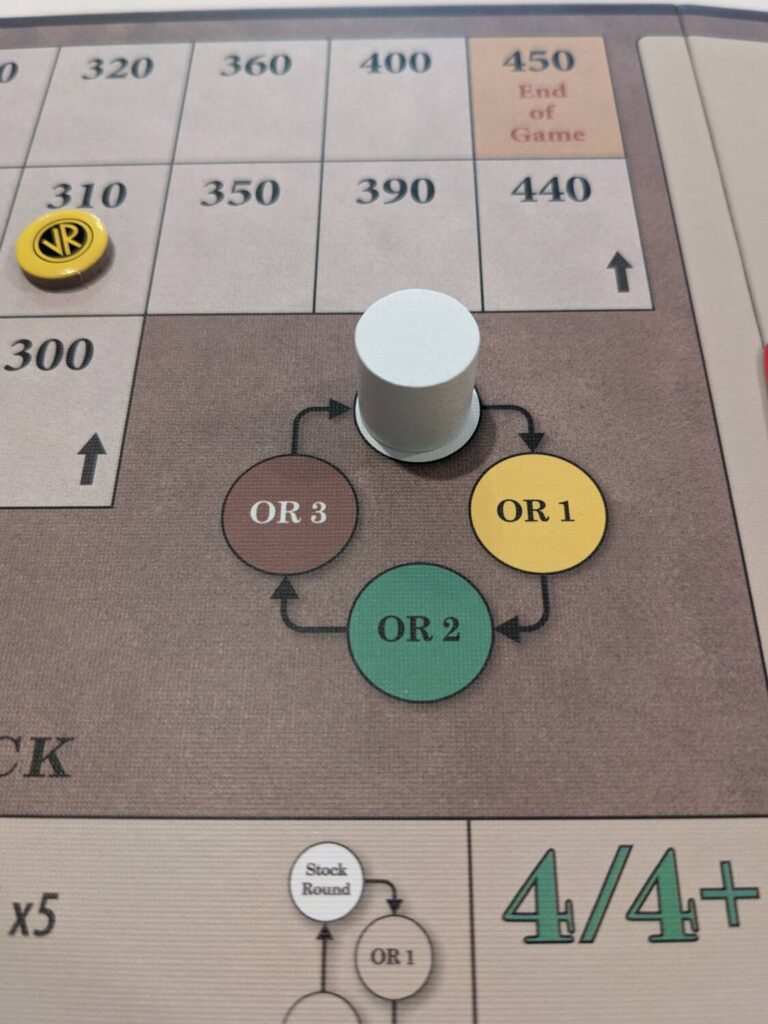

1848 is a knife fight. Even in an environment with better etiquette, the map is relatively small, especially when considering the layout on the western and southern fronts. Seven of the eight corporations operate so close to each other that just racing to get station tokens out is a thriller. The permanent train pool is so small, SO SMALL…only three 5/5+ trains are in this game, and only two 6/6+ trains. (1848 features gauge changes, so the plus trains include one free gauge change between narrow, standard, and broad gauge routes shown on the map. This is vital for the companies that need to operate trains that travel across distant map sections.

The Final Reckoning

1848’s decision space—at least, the space after the private auction—is fascinating, and after ten games I’m still playing around with how different companies affect map development. I love the Bank of England, and the pressure it puts on players new to the game as they try to manage the cash their corporations have in the treasury. Do you want to withhold, or take loans? Will you be ready to buy one of the cheaper permanent trains at the right moment, since 3/3+ and 4/4+ trains have to be bought before the permanent train doors can open?

Because the bank is so large in 1848, I’ve sometimes seen players milk it with 4/4+ trains to earn as much money as they can and not have to worry about 8/D trains being bought to rust the 4/4+ trains. I’ve seen players have just one company and a 5 train win as often as a player that has two companies, one with a D train and another with a permanent train plus a 2E (The Ghan) train win here. Lots of ways to skin a cat, and lots of weapons to use to skin that cat…it’s a really flexible play space.

1848 has triggered the kind of bad behavior that 18xx games can be known for, so it’s not a great game to kick off a journey into this space. I like it for that, but even I admitted above that I have had a rough game or two…much rougher/meaner than other games. It’s an adjustment, one that I have successfully planned around with progressive plays. But this is the kind of game that you might lose a friend over, if that player is as sensitive as I was to aggressive play.

The GMT production of 1848 is stellar. Like 1846, the rules are laid out well, the boards are incredibly sturdy, and the tiles/station tokens/corporation mats do the job. If Shikoku 1889 is the league leader in beautiful 18xx production right now, 1848 is a tier below that and does everything a game like this needs to do to impress a gamer. Just don’t use the paper money, and you’ll be fine.

1848’s place in 18xx lore is well deserved; it’s a great design that adds elements to keep gameplay fresh after multiple plays. Ohley and Orgler, the minds behind other train game classics like 1880: China and Russian Railroads, are some of the most creative people in the 18xx space. Give this a look!

Add Comment