I have become lost in the dusty, isolated, weirdly moist corner of board gaming with all the war games, those aesthetic heretics with demanding rule sets and titles like Axis of Forgiveness: The Macedonian Civil War 230-173 BCE. How I got here, I do not exactly know. I was looking for my copy of Blokus and tripped, running headfirst into Conquest & Consequence, which seems to have left me confused and concussed.

Unable to see in the darkness, I stagger forward with my hand running along the shelf, both for stability and to make sure I don’t travel in circles. I have heard the horror stories, as we all have, of people ending up lost in war gaming forever. I will survive to see my friends, I will survive to play Blokus again.

I hear a constant, low buzz. I swat at invisible mosquitos who do not disband.

I think I’m headed in the right direction. The air grows less stuffy. I see light. As I near the fluorescence of the better-illuminated areas of the basement, my hand catches against a box protruding a few inches from the shelf.

Sure that I can find my way out of the war games from here, I pull the box down to take a look. It is emblazoned with the colors of the French flag and a detail from a painting by Georges Clairin. I am holding a two player game from GMT called Red Flag Over Paris: 1871, The Rise & Fall of the Paris Commune.

The buzz grows into a hum.

I read the back of the box for some context. Following France’s quick defeat by Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War, the National Guard troops who had defended Paris seized control of the city. They declared Paris to be independent and self-governing. After two months, the army of the French government based in Versailles seized the city, killing anywhere between ten and fifteen thousand Communards during what the French call La semaine sanglante, the Bloody Week. I have never heard of this. In the game, players take on the role of either the Communards or the Versaille government and fight for control of Paris.

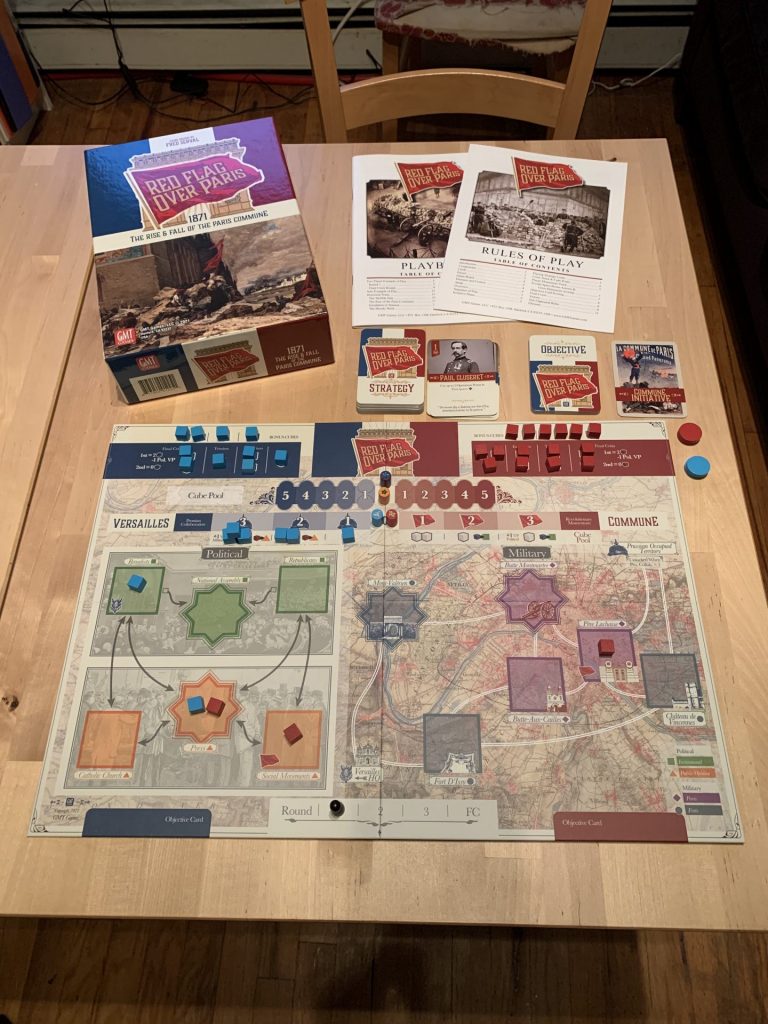

I open the box to find two instruction manuals: a thin booklet called Rules of Play which contains all of the rules in indexed format for easy reference, and a beefier Playbook, which includes multi-page, step-by-step illustrated examples of both the two-player game and the solo variant. The components are simple, attractive. The cards are on thick card stock, the pieces are boldly colored wooden cubes and cylinders. Something to be said for simple components in what I assume will be a complex game.

The player board is handsome and legible, divided down the middle into the two areas where I will need to engage with my enemy: areas of military engagement in and around Paris, and areas of political struggle, including the Catholic Church, the Press, and the National Assembly. In order to win, I will need to conquer not only the battlefield, but the hearts and minds of the French people.

Using the Playbook, I complete the example of a two-player game to learn the ebb and flow of play. It seems to be a typical card-driven area control game, and the mechanics themselves are simple. I receive a hand of four cards each round. I play three. Cards are played either for their events or for Operations Points, which can be used to place or remove cubes. The events are typically more powerful, but the Operations Points provide greater flexibility in where a player can act.

“That’s it?,” I say in disbelief. I thought war games were supposed to be difficult.

The hum becomes a thrum.

I set up the solo system. It takes some time to internalize the decision tree, but it proves a worthy opponent. The game is brisk but deep, every choice satisfying and impactful. The fourth card from each round is set aside to go in my hand for the closing Final Crisis, which provides an element of long-term planning that I enjoy. I have to be mindful of not only my board position, but the number of troops I have available. When I bullishly deploy all of my soldiers before the Final Crisis, I realize that I am paralyzed and in no state to react to whatever my opponent does during those final, powerful card plays.

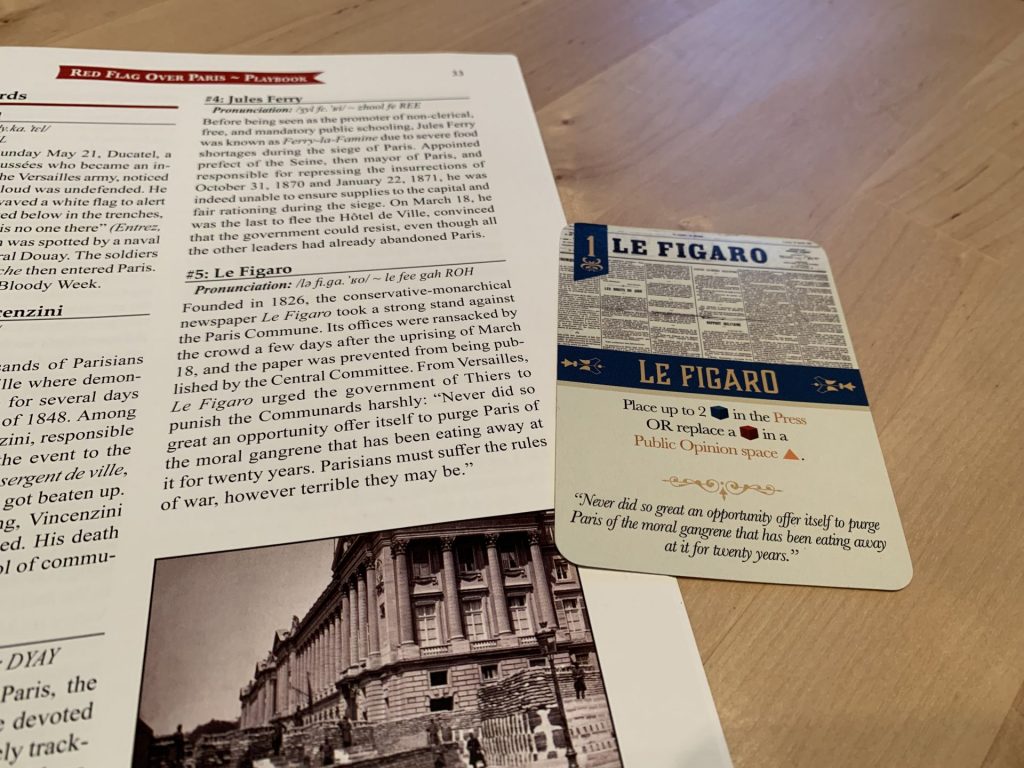

Beyond the excellent gameplay itself, I find myself drawn inexorably and inextricably into the world of Red Flag Over Paris. The last 22 pages of the Playbook provide extensive historical context, designer’s notes from Fred Serval on the game and its influences, and an absorbing nine-page section discussing each card individually, going into who the person or what the event depicted was. I spend an hour or two going through the deck card by card, reading each entry, delighted by the thoughtful ways in which the history behind each card impacts its in-game effect. Was this made just for me?

The thrum is now akin to the pounding of drums. I could swear I hear a choir singing “Est nostrum” over Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms.

I pack up the components, the board, the pair of manuals, and replace the cover. I slide the box back onto the shelf. The box, like the components and board, is handsome. It strikes me as large considering that Red Flag Over Paris was designed with the intention of being a quick lunchtime game. Not the most portable size. That is my only reservation.

I stand there for a moment, on the precipice of returning to where I’d started. I finally see my copy of Blokus just a bit further along to the right, in the well-lit common area. I bite my bottom lip and drum my fingers on the shelf. The music, the thrum, the hum, the buzz has subsided. All is quiet now.

I walk over to Blokus, pull it off the shelf, tuck it under my arm. I turn around and return to the darkness, to see what else I can find.

Add Comment