From the 1870s to the 1890s, a couple fellows named Marsh and Cope took paleontology battles to a whole new level. You know how it goes. First Cope assembles a skeleton backwards placing the head on the tail (been there, done that) and is humiliated by Marsh. Then Marsh pays off the field crew to send the good fossils his way and all heck breaks loose between the two.

But the “Bone Wars,” as they came to be known, were as fruitful as they were dirty. More than 130 species were discovered by the two rivals—a frantic pace of exploration indeed. If you’re like me, you’ve long waited to take part in such a battle all your own, only with the dinosaur heads mostly on the proper end. Well, the wait is over.

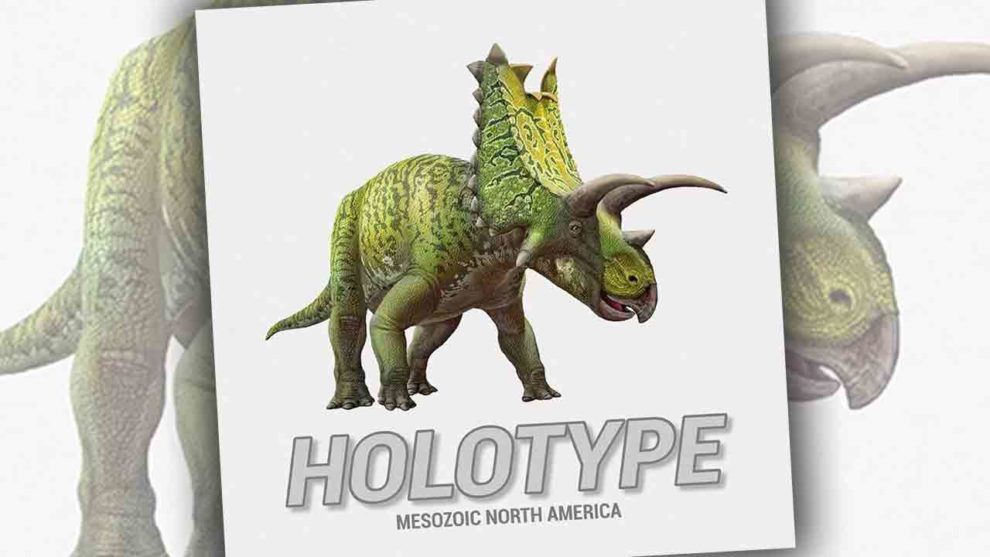

Holotype: Mesozoic North America is the first title from publisher Brexwerx games and designers Brett Harrison and Lex Terenchin. Players take up the role of Paleontologists competing (peacefully, I trust) to publish their way to the peaks of academia—or perhaps the high deserts of academia would be more favorable in this case.

What do you call a paleontologist who naps on the job?

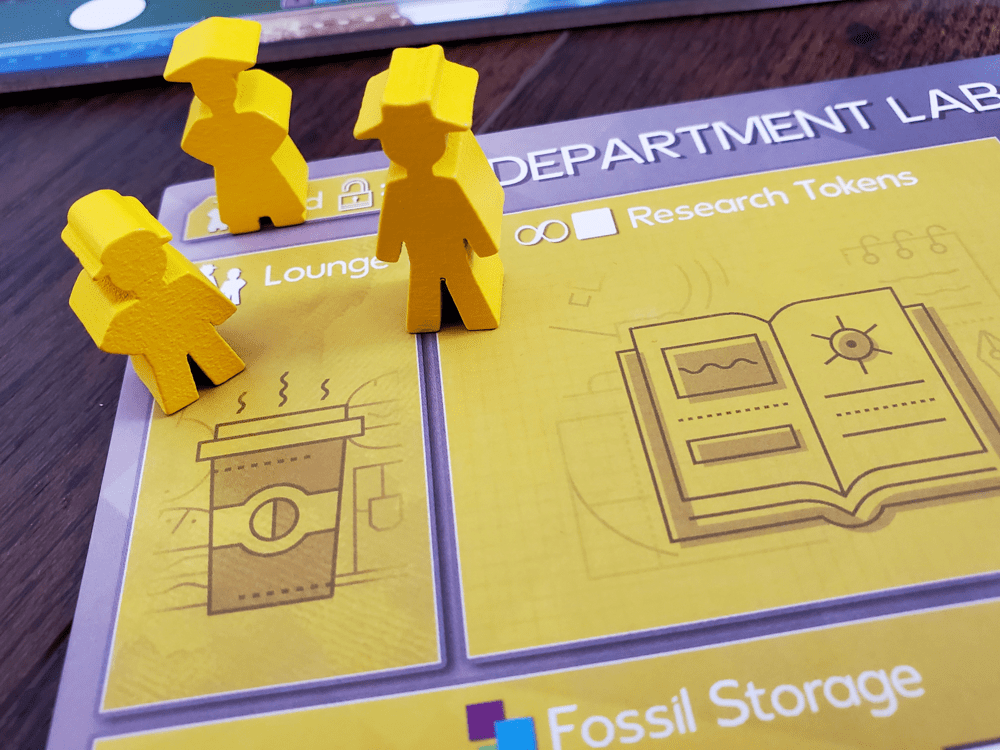

What makes Holotype fascinating as a worker placement game is the hierarchy of worker meeples. Each player begins the game with a Field Assistant and a Paleontologist, with a Grad Student waiting in the wings to be released after the player’s third publication. The Field Assistant has lesser capabilities at each of the game’s locations, or in the case of publication, no capability whatsoever. Choosing the right worker at the right time in the right place—this is the heart of the decision space. Adding a layer to the process, worker bumping is also affected by the hierarchy. Meeples can bump their own type or smaller when there are no free spaces at a location.

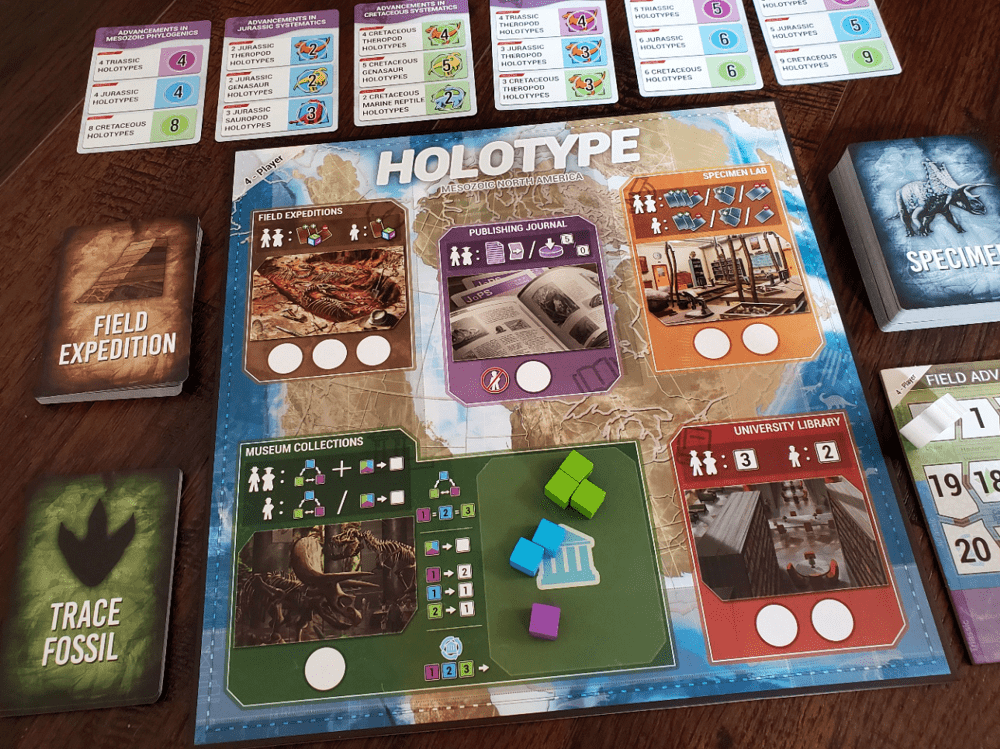

The base process is simple: Gather the fossils (cubes) and research (cubes) necessary to publish a new dino-specimen from the cards in hand. Toss in a trace fossil (bonus card) every now and again to sweeten the pot. For a bit of variety in scoring, add markers to the global objectives based on the Holotypes already in play. When enough species are published or global objectives met, the game ends immediately.

Turns are also simple. Place a worker or bring the workers back to the Lounge along with a research cube. Five locations drive Holotype’s action. Field Expeditions allow players to draw a card and roll the indicated dice, collecting the fossil cubes and maybe a trace fossil card. The University Library dispenses research cubes. The Specimen Lab is the home of dino-cards where players draw and discard species they’re interested in pursuing. The Museum is the home of fossil trade and the Publishing Journal is the supreme bumping ground as players reveal their work to the world.

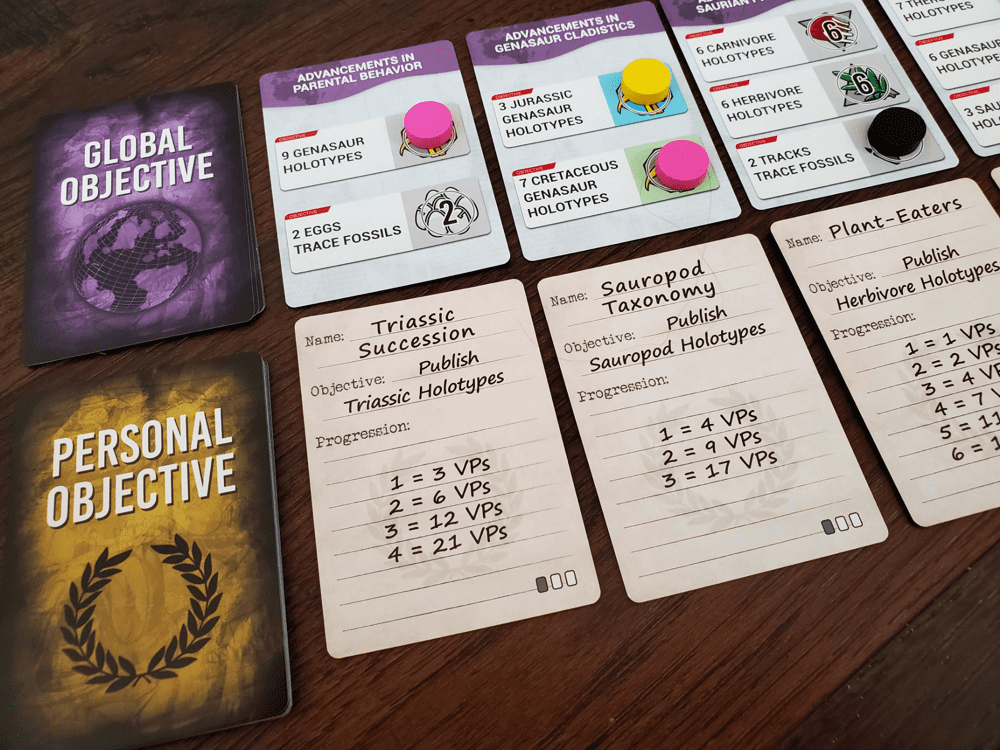

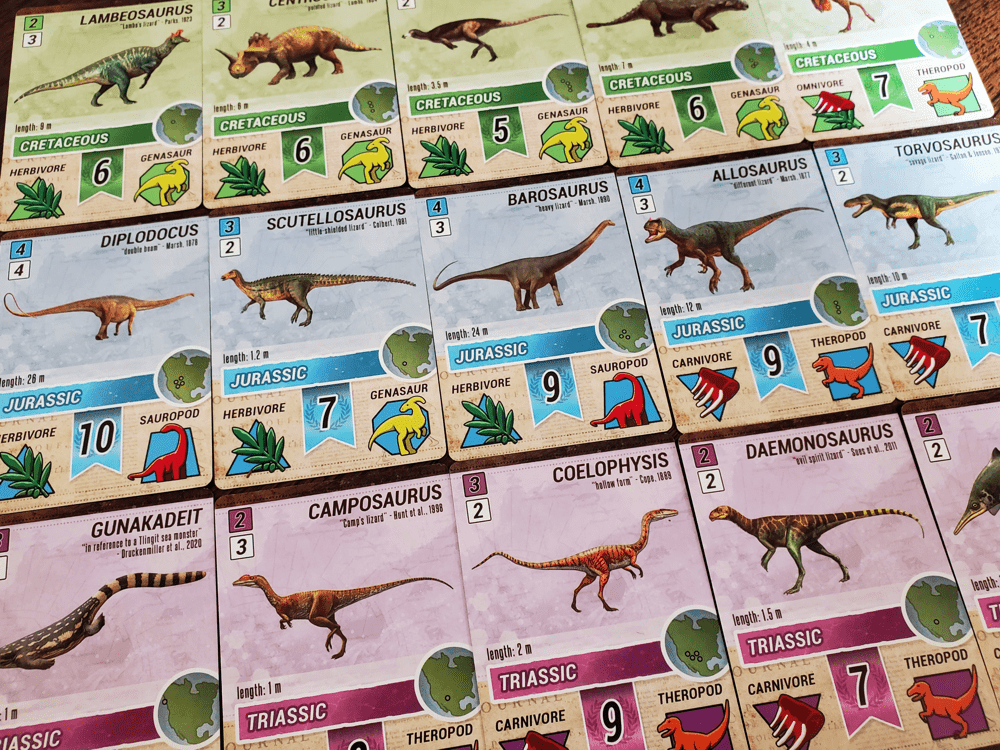

Each dino-specimen boasts a victory point value for the endgame should it be published. Each card also has a wealth of additional information across the bottom third for the tracking of global objectives. Species are designated by geologic period, diet, type, and size.

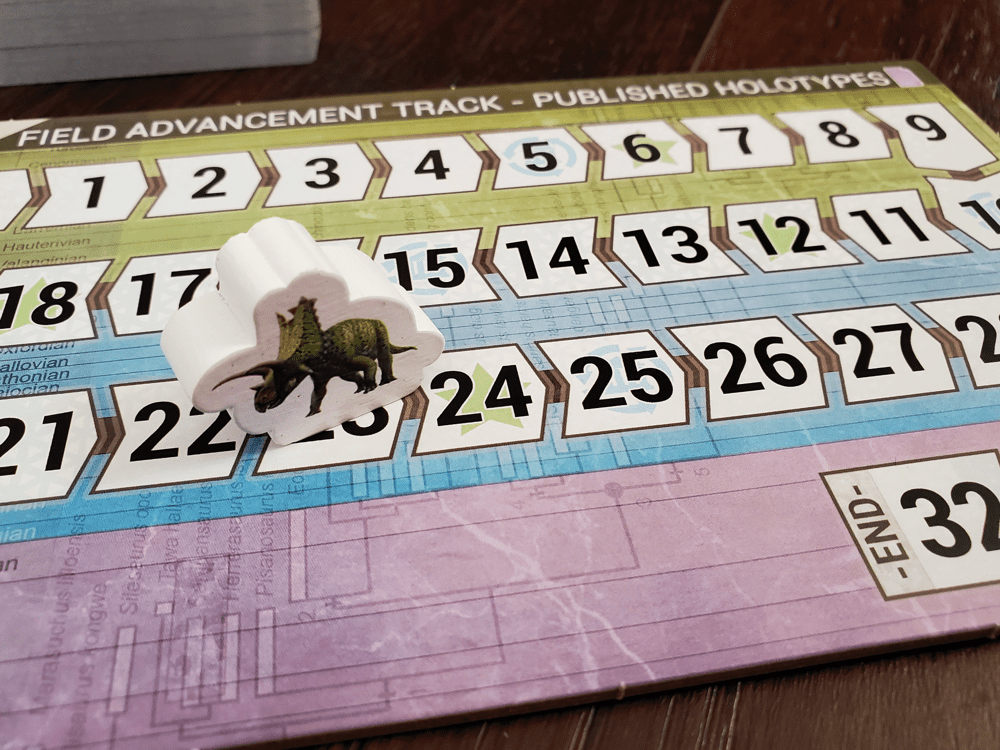

As cards are published, the tracker moves along the Field Advancement Track which serves as a game timer. Every so often as the tracker crosses a Milestone star, players add a special ability to their repertoire, most of which bestow an extra cube or card with various locations. Also dotting the Track are Museum icons that call for a reset of the Museum trade floor.

The Museum location is a bit of a lifeline throughout the game. Most of the fossil cubes come from Field Expeditions, but frustration abounds when the cards fail to provide the needed color. While the Museum trade floor is somewhat dependent on the needs/uses of the players, it still represents the best way to turn three purple cubes into four blues and three greens, if you know what I mean.

Holotype ends abruptly. Once the tracker hits the end of the Track or a certain number of global objective cards are full, it’s off to the scoreboard. Points come from Dino-species cards, trace fossils, the number of discs played on global objectives, and a personal objective card chosen at the beginning. Players lose points based on the research cube value of any cards left in hand and crown a Paleontologist Supreme.

Lazy bones!

Holotype is one of the most straightforward worker placements games I’ve seen. There are minutiae among the rules that matter—placing excess gained fossils in the museum, only bumping when there are no available spaces, etc.—but the rules are almost entirely intuitive for any players with a few worker placement games under their belt. The danger in a straightforward game, especially one that involves gaining cubes and trading cubes to buy cards, is that it becomes a bit of a snoozer. Toss in a very straightforward approach to graphic design and illustration, and the danger is amplified.

During the Kickstarter, Brexwerx shared their meticulous approach to crafting a balanced design via playtesting and Python simulations. I believe this attention to detail is what keeps Holotype out of trouble—mostly.

Any game in which every third move will be picking up workers will start slowly, but I do enjoy the hierarchy of worker placement. The decision to limit the Field Assistant is rather brilliant because on most turns you’d rather send the other workers. This strange reluctance keeps life interesting. Knowing it takes another Paleontologist to bump a Paleontologist means you might be able to clog a spot and force another player to place their workers in a less-than-preferable order. It’s subtle, but nice.

There is a great balance among the various scoring opportunities as well. The dino-species provide the most accessible value. The trace fossils are rare and random, but extremely valuable because they have so low a cost. The global objectives are often a sniping battle since one player makes the objective available and may not have the chance to capitalize before it’s claimed. On the scoreboard, this means one player may gain 9pts for a specimen, but then another may immediately add 7pts via the objective cards.

Where Holotype struggles (other than the fact that nearly every time I’ve typed the name, my fingers have produced Hologype) is in the lower player counts. There are different game boards for every player count to ensure tight placement. There are unique Advancement Tracks as well plus a set number of global objectives to match. Proportionally, the math may work, but in practice some of the magic dissolves in a duel.

Practically, the global objectives are nearly invisible until there are four players. I suppose it’s not a big deal, as the lower count game feels more like a pretty open ended race to publication, but they just sit there like an academic ghost town. Depending on the card draw, sometimes the objectives aren’t available until 75% of the Track is covered. At that point, it is more lucrative to just press on with publications to the end, especially as it nearly forces the opposition to keep up. Similarly, the Museum is proportionally less useful when fewer players are feeding the pool.

The result is that my favorite experience is at four players. From a time perspective, this keeps the game length reasonable at 75-90 minutes. Plus, with that much humanity at the table, someone will break the ice on global objectives by the midway point if not sooner. In fact, someone will likely keep research cubes handy to make sniping the globals a major scoring strategy.

Which brings me to the only other gripe that has come up during our plays. I mentioned the amount of information on every card. As they are splayed out around the table, it becomes a bit of a chore to parse the situation, primarily because there is no one way to organize the cards. You could organize them by geological age or diet, but the other icons won’t line up no matter what you try. There’s just no clean way to know what’s out there. I suppose a sharp eye is part of the experience, but it’s the least clean part of the design.

The graphics and artwork are so clean, on the other hand, they’re almost sterile. I love a stark white box, and Holotype certainly qualifies. The insert is a bit generic—and hides a lovely printed map—but highly functional. The rulebook is precisely arranged with some of the rule quirks highlighted in special boxes for high legibility. The spreadsheet-ish player board works without flaw. The game setup looks like a clean lab…even the dirt! The only place this cleanliness breaks is in reading the card info around the table. There’s just a lot going on there with colors and symbols and (unnecessary) background shapes. It’s busy.

Holotype reminds me of a couple games I enjoy. It has the scientific publication race that keeps The New Science in my collection. It has the send/bump/gather worker placement—and the subsequent slow acceleration—of Asking for Trobils (or Charterstone on the legacy front) that my kiddos enjoy so much. Plus it has some of the glorious collect-and-cash cube and card play of Cytosis, with a very similar scientific vibe to boot. I’m not sure it supplants any of them in my heart, but there’s a lot to enjoy.

For the paleontology fan—for, at its heart, this is a paleontology game far more than it is a dinosaur game—Holotype delivers. For the science gamer with three friends, it delivers even more consistently. There is a Pterosaur expansion in the aether already, plus a larger European expansion with several bonus offerings and a solo mode coming to Kickstarter in summer 2023, so the pipeline is full and ready to unleash a torrent of ancient goodies soon enough.

In the meantime, this clean white box contains a clean light strategy experience.

Add Comment