The many novels of Paige Turner loom large in the collective memory of pulp enthusiasts. Academics may not make much of The Angel of Death or Land Out of Time, but collectors have a lot of love for Turner. Her brisk pacing, her sharp prose reminiscent of a less-refined Chandler, and her efficient character development have won hearts for the past seventy years.

Turner’s central gift was her ability to use tropes without leaning on them. You go into Lady of the West knowing the hardscrabble heroine from the hundreds of times you’ve encountered her before, but Turner’s prose keeps her from feeling worn. You can see her, you can’t see through her. Turner likely felt some sense of kinship for Lady. To paraphrase Lady of the West’s tagline, pulp was a man’s world, and then she came along.

Chapter I: Source Material

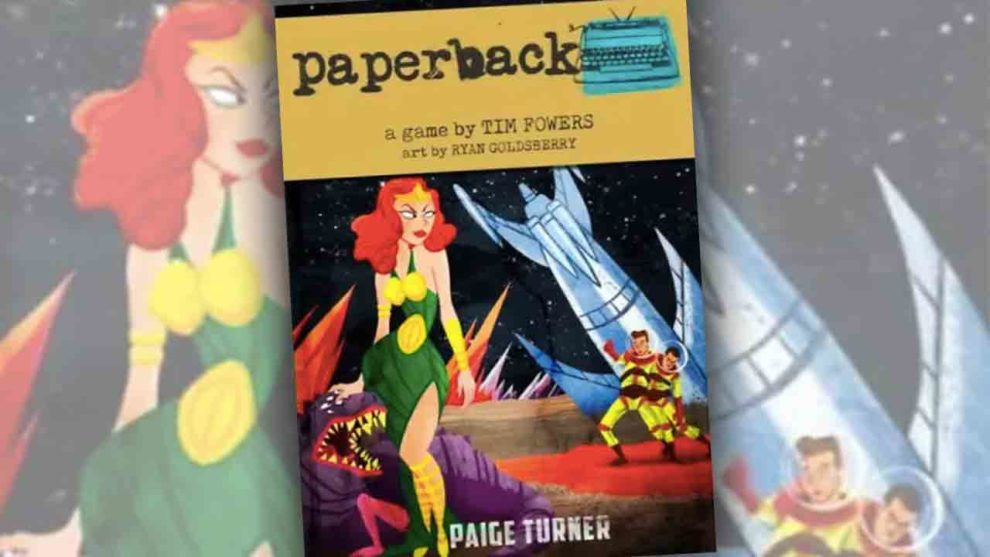

Paige Turner is the fictitious author responsible for the equally fictitious books showcased on the box for Paperback, Tim Fowers’ 2014 deck-building word game. Paperback is openly modeled on Dominion, Donald X. Vaccarino’s massively influential design. Vaccarino is given thanks in the manual “for creating a genre,” which is entirely appropriate. Without Dominion, Paperback likely wouldn’t exist at all.

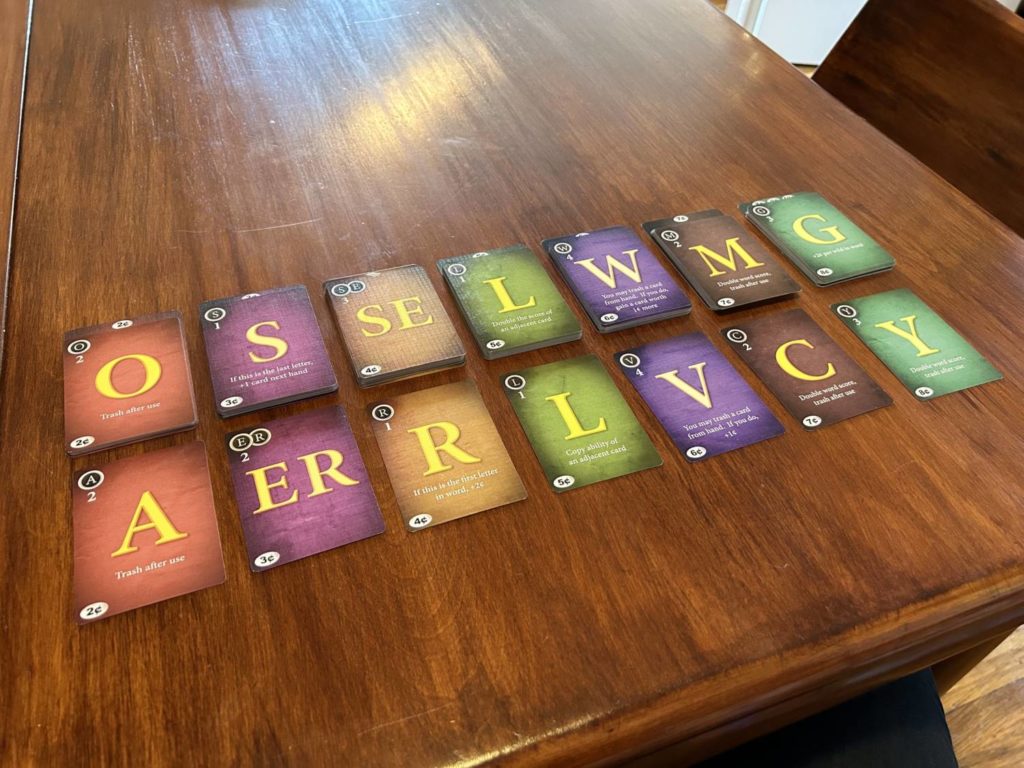

If you’ve played Dominion, you know what’s going on here. Every turn, you draw five cards from your deck, playing them for optimal effect. The wrinkle is that each card showcases one or two letters, and you have to spell a word to play the cards. Most letters give you money, which can be used to purchase further cards from the market, and abilities, which will either allow you to remove cards from your deck or influence your buying power in some way. The market is chock full of letters, which add their own abilities and monetary values, and scoring cards, which net you points at the end of the game.

Chapter II: Revisions

Fowers made a few smart tweaks to Dominion’s formula. Like any card game, deck-building games are subject to a certain amount of luck. That’s part of the contract. In a game centered around spelling, the luck of the draw could be disastrous. Nobody wants to play a game that constantly grinds to a halt.

Paperback accounts for this with Common Cards. There’s always one available, and it’s almost always a vowel. On top of that, the scoring cards act as wilds. They don’t give you any purchasing power, and they certainly don’t give you any abilities, but they can help in a pinch. This avoids Dominion’s dreaded handful of green, a turn in which you can’t do anything.

There are two end triggers. Like Dominion, running out of a specified number of scoring cards will do the trick, but you can also end the game by playing a word of sufficient length. The Common Card changes each time a player hits a threshold between 7 and 9 letters. Once someone plays a 10-letter word, that’s a wrap.

Chapter III: Odds n’ Ends

The second person thanked in the manual is artist Ryan Goldsberry, who did a wonderful job. His mock book covers are evocative of the theme, and give Paperback an enormous amount of charm. I love the included card dividers, which make setup a breeze. The manual is poor, a consistent issue across Fowers’ games. Hardback, the sequel to Paperback, also has a miserable manual, and I’m told Paperback Adventures has the same issue. These are simple games, their manuals shouldn’t be so daunting.

I love word games, and the process of piecing together something coherent from a jumble of letters. In that regard, I enjoyed Paperback quite a bit, though I don’t find it as satisfying as Hardback. Longer words are harder to come by, and longer words make me feel special. The word is so long, I am so smart.

If you’re looking for a word game to break out for game night, Paperback is a fine choice. It’s de rigueur deck-building married to Boggle, Scrabble with shuffling. Unlike Paige Turner, Paperback can feel a bit like it’s leaning on tropes. There are other games that do each part of what it does better, but Paperback does the whole pretty dang well.

Add Comment