Games should be more restrictive about player count. I sympathize with publishers and recognize the act of commercial suicide that is a game requiring an exact player count. Look what happened to Deal with the Devil. Granted, I don’t think the restrictive player count had anything to do with that game’s disappearance. If anything, the requirement of exactly four players got Deal more attention than it would have otherwise gotten. It would have helped if the game were any good.

Alas, it wasn’t, and Deal with the Devil immediately faded from public awareness. For a brief, glimmering moment, I knew hope that the buzz around Deal might lead us all a little closer to the light, towards an age of radically honest player counts. You can tell me Votes for Women is for 2-4, but we both know it’s a two-person affair. You can slap a 2-4 on the side of Flamme Rouge, but that doesn’t change the fact that the game needs at least three.

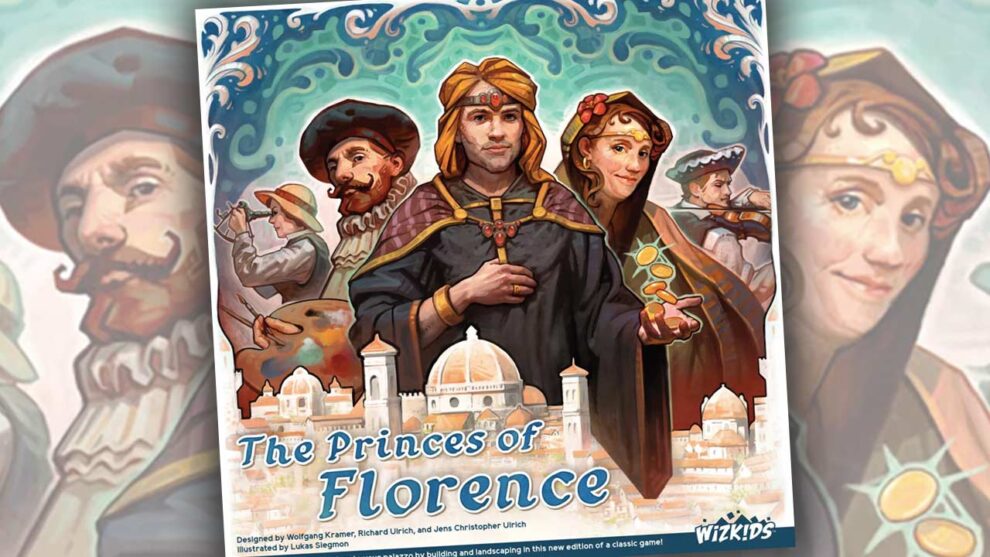

All of this is to say that The Princes of Florence is a five-player game, and only a five-player game. The box says 1-5, and you can technically play it at any of those counts, but you only experience The Princes of Florence properly when you play it at five. Any other player count is a noticeably lesser game.

A Roadmap to Florence

In the center of the table sits a board, divided into two halves. The left half contains the Objects that will be auctioned off during the first portion of each of the seven rounds. There are seven distinct types of Object, each with its own purpose. The Objects you acquire ultimately steer and determine your strategy. On the right side of the board are various Buildings, along with a few other items that can be acquired during the second half of each round.

Before we talk about the auctions, I should explain to what ends these be. Ultimately, in The Princes of Florence, points come from attracting Professionals, the artists and scientists who will paint for you, make maps for you, write music for you. Each time you attract a Professional, which is played from your hand, they complete a work. That work has a certain value, determined by a variety of factors, including the various Objects you’ve acquired across the rounds. It’s up to you whether you then want to keep all of that value as cash, or if you want to turn any portion of it into points at a 2/1 ratio.

Alright, where were we?

The starting player picks an Object to auction off. Let’s say I decide to auction off the Builder, who lowers the cost of adding buildings to your estate. The price is fixed: 200 Florin. Every time, the opening bid is 200 Florin. The next player has two options: they can either pass, of course, which means they will not be purchasing the Builder this round, or they can raise the price by exactly 100 Florin.

This is already interesting. You can’t jump a price up out of nowhere. You can’t bid aggressively, all at once, scaring everyone else away. The Princes of Florence necessitates patience. When I read that rule, I wasn’t sure how I felt about it, but there’s terrific reason to it. If I’m the starting player in a game of five, and I pick which Object to auction, I have an immediate, reasonable estimate of how much it will cost when it gets back to me. That’s fascinating.

Whoever wins the Object, placing it as necessary, then puts their player pawn on that Object on the board. That Object cannot be auctioned again this round, and that player cannot participate in auctions either. A perfect rule. It simultaneously increases the stakes of each auction, since this is your only chance to get that Object this round, and it decreases the willingness of players to bid on objects when they’re really only interested in driving the price up. The next bit of strategy: the starting player for the round continues to pick what goes up for auction for as long as they don’t win, until one Object per player has been auctioned off.

This has likely been a slightly overwhelming series of paragraphs to read, and I’m sorry about that. It’s that kind of game. The rules are subtle but finely tuned, and the implications are likewise.

Once all five players have won an Object, we move on to the second half of the round, during which players can perform two out of a selection of five actions. This is when you can build Buildings or play Professionals from your hand, for example. Beginning with the starting player, each player performs their two actions.

Buildings and Freedoms, the two types of tiles available for purchase here, help make your estate more attractive to Professionals, increasing the value of their works. Player order does matter, as all the tiles are supply-limited, and there is definitely not enough for everyone.

Once the second half of the round is complete, the starting player token moves clockwise, and you do the whole thing again.

Così buono

I have nothing but great things to say about The Princes of Florence. The design is tight, with no frills. Every rule exists for a clear, discernible reason. The mechanics are simple once you know them, though it is a surprisingly difficult game to grok if nobody at the table has played before. Turns are quick. Auctions are succinct but tense. The game rewards a wide variety of strategies and approaches. It is a Euro, but there is no objectively right choice. This is a Euro married to the sorts of slightly impermeable, muddy decision spaces I prefer.

How do I put this? The Princes of Florence is a Euro that understands why I love trick-taking games.

Euros are not my first choice for gaming. Most of them are too isolating, and I prefer more interaction. To play Florence, you can concern yourself only with what you’re doing. To play Florence well, however, you have to know what everyone else is doing too. You have to pay attention to where you are in the auction rotation, and use your position to your advantage.

A key distinction for me has to do with the degree to which you can plan ahead. I find most Euros to be anxious experiences. I don’t like the feeling of having my next several turns planned out while having to wait to execute them, with nothing to stop me from being able to do all of it. It is good to be able to plan ahead, to have a mix of tactics and strategy, but I prefer a mix. Part of the beauty of The Princes of Florence is the reactivity of the space. What other players put up for auction, and when, can have a big impact.

An example of what I’m trying to get at here: In my first game, I immediately knew I was going to focus on building lakes. All three of the Profession cards in my hand benefited from lakes. It was the obvious decision. In many games, for me, that’s already the death knell. My decisions have been made for me and I just need to pull them off. Not the case with Princes of Florence, though. The timing and tension of the auctions, the imperfect math of “How much of this do I take as money, and how much do I take as points?,” the way you grow into understanding the economy, it creates a living, dynamic space.

Back to the Player Count

The thing is, this game works fine at any player count. Sure. But it’s miles ahead at five. Five is just the right number. Five creates greater freedoms—one more Object per round up for auction—and greater restrictions—more competition for those Objects. Five guarantees that one other person at the table is going to want to compete with you for that Object. At four, it devolves into multiplayer solitaire. At three, the auctions don’t matter. At five, it’s a masterpiece. A weird, singular masterpiece.

I am thrilled The Princes of Florence is back in print, and that Wizkids and Korea Board Games have done such a handsome job with it. If you’re looking for something you haven’t played before, this is the one. It’s full of interesting, intentional, uncertain decisions. It’s full of the alchemy of human interaction. It has immediately made a place for itself as one of my favorite heavier games. Just make sure you play it with a full table.

I have this game and I have played countless games at four players. I have never experienced a five player game, and now I am quite certain I have never actually experienced this game.

My friend Mike is a mathematician who managed to ‘solve’ several aspects of the game. Being the kind of guy he is, he shared his solution, which meant that our games shifted from a slow wait to see how many points Mike destroyed us by, to a game that has some very good, close scores with fights over this freedom or that, that building or the other one, and so on.

It is a great game. I love it. But now I *need* to play this at five players or I am going to go bonkers.

I remain fascinated by the ways in which that fifth player modifies the playing experience, how it manages to make everything harder and more liberated. Love this game. I hope to play it many, many times over the years to come.