The Crew: The Search for Planet Nine is one of my favorite games. The combination of trick-taking with a cooperative format was entirely novel to me, and jump-started my fascination with trick-taking as a genre. With the release of The Crew: Mission Deep Sea, which somehow managed to improve on the original, publisher Kosmos established an unassailable line of trick-taking credit.

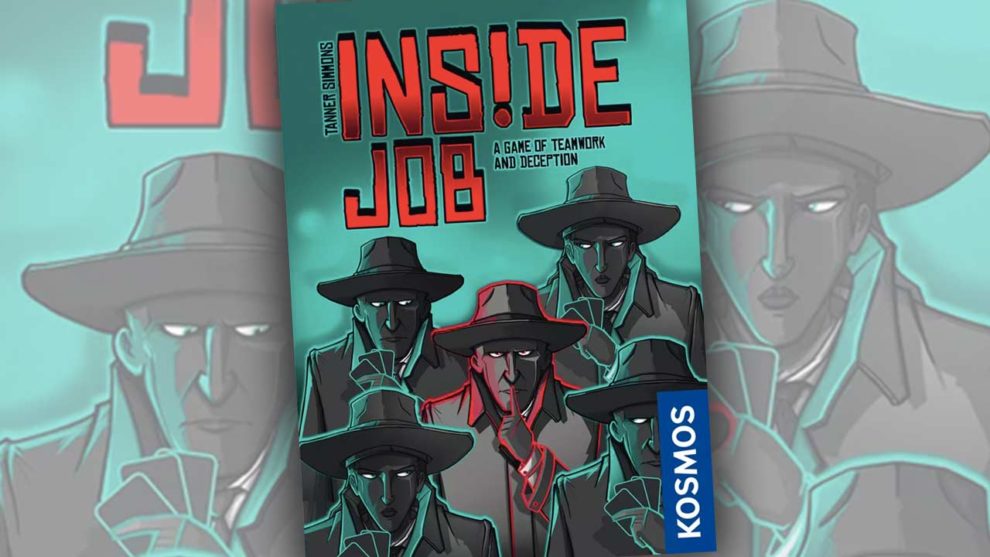

I think of Inside Job, another trick-taker with another novel approach, as being the spiritual successor to those games. This is the third game in the Kosmos Trick-Taking Universe, the moment the publisher looks around and asks, “Are we going to do a whole line of small box trick-takers?” This time, trick-taking has been welded onto a hidden role social deduction game. I was not only excited by the announcement of the game, I was intrigued.

The good news: Inside Job is certainly intriguing. The bad news: Inside Job is not, in my experience, very good.

Tricky Business

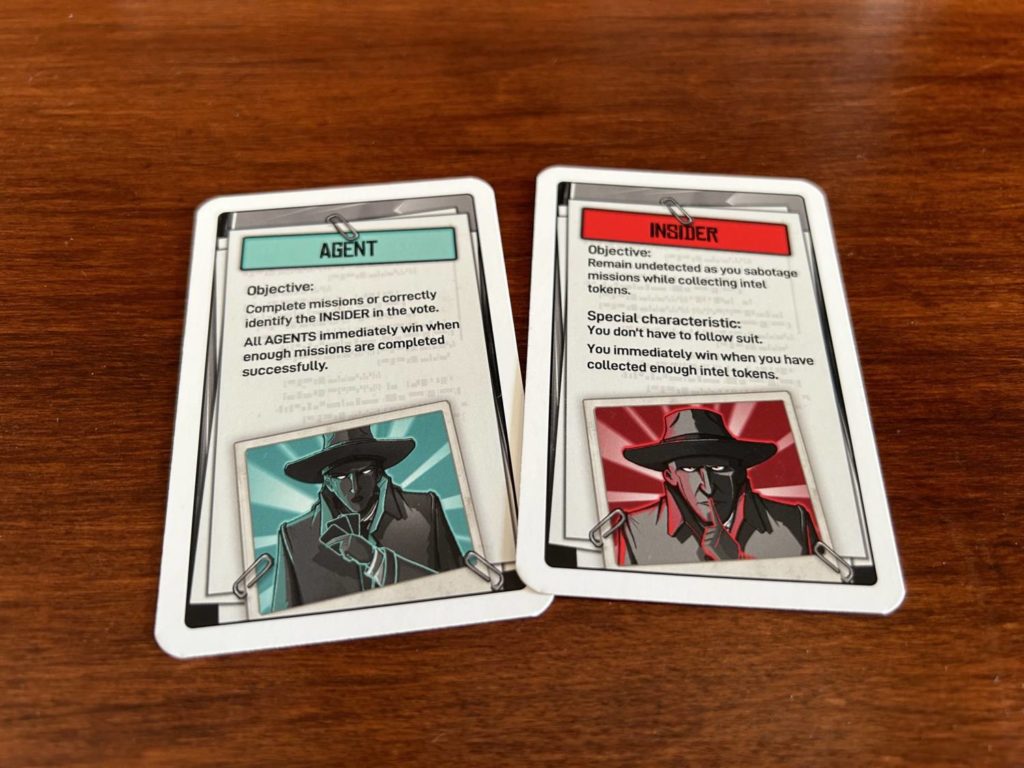

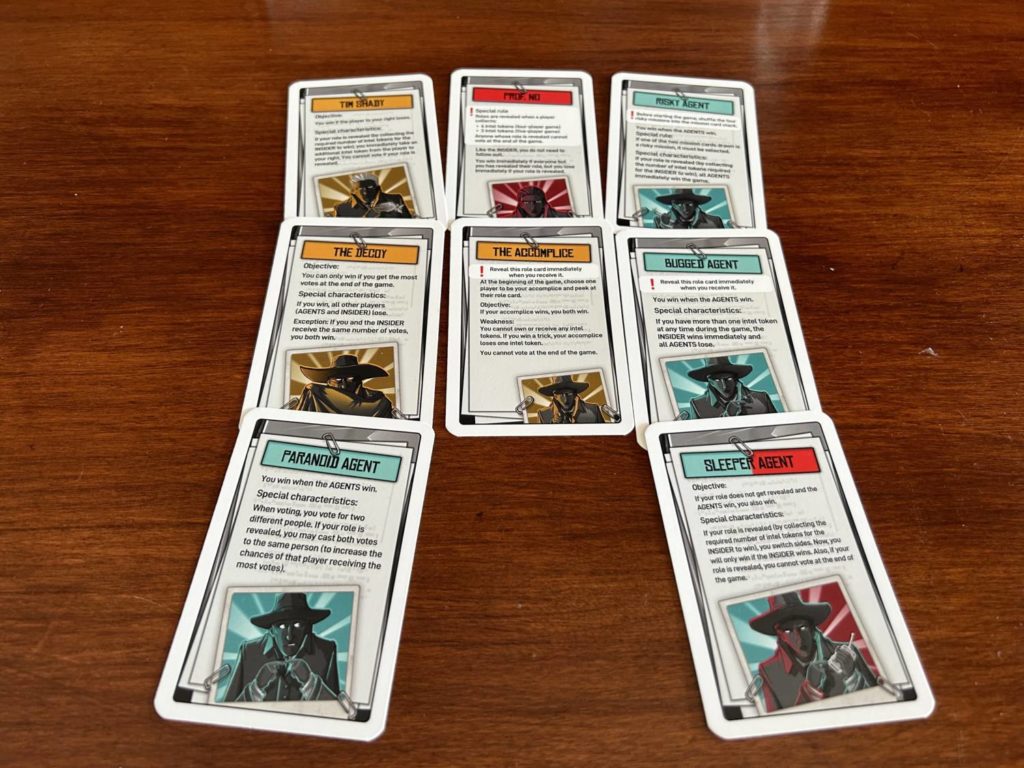

Inside Job has a few layers of complexity. The manual suggests adding them in one step at a time. In the simplest version, players are divided into two teams. One player is the Insider, a mole, while the others are all Agents. You do not know who anyone else is, of course. That would ruin the deduction part of things.

Before starting each trick, the leading player draws two Missions from the Mission Deck and chooses one of them. Those of you who have played either Crew will recognize the idea. Missions say things like “The cards have to be played in increasing order,” or “The second and fourth cards have to be on suit.” If the table as a whole accomplishes the task over the course of the trick, the mission is a success.

If the Agents manage to complete a given number of Missions, they win. Conversely, if the Insider manages to win a given number of tricks, the Insider wins. Should neither of these conditions be immediately met, the participants vote on the identity of the Insider. If they’re right, the Insider loses.

Each Mission specifies a trump suit, and, unlike everyone else at the table, the Insider can play off suit whenever they want. This is when the game starts to fall apart. In the simplest version, when the Insider has to win relatively few tricks, why not just play off-suit to match the trump at every chance you get, muscling your way to victory? Sure, players could default to choosing a Mission with a trump suit they have in their hand, but sometimes that’s a bad idea, or simply not possible. It gets worse.

The Trick Who Came In from the Cold

Every time you win a trick, you take an Intel Token. Without extra rules, these cute little briefcases are redundant. They simply signify a victory. In the full game, though, Intel Tokens can be wagered.

Here’s how this works: When you play a card, so long as you aren’t leading and so long as your role hasn’t been revealed, you can add an Intel Token to your card. Your card is now treated as part of the trump suit. If anyone else wagers an Intel Token during the same trick, the winner takes all.

The idea of this is sound. You create a thick web of uncertainty and paranoia as everyone tries to one-up the rest of the table. Who do you trust? In reality, though, it’s just…I don’t know.

I’ve played Inside Man five or six times now. The best games were the first two, when the person who ended up being the Insider kept forgetting that they could choose to play off-suit. That meant we were playing an honest trick-taking game where we each had different goals, and that was pretty fun. That makes me wonder if Inside Man has been overdeveloped.

Part of the beauty of trick-taking games comes from the tension of never quite knowing how your choices will play out while knowing enough to have a sense of the odds. That’s what makes pulling off a successful round, whatever that means in the particular game that you’re playing, so satisfying. Designs that add too much net uncertainty to trick-taking spoil the recipe. With bidding and hidden roles, there’s too much here that we don’t know.

Maybe you could argue that that’s method for a design about spycraft. It’s not a good game, though.

Sounds like this reviewer hates fun