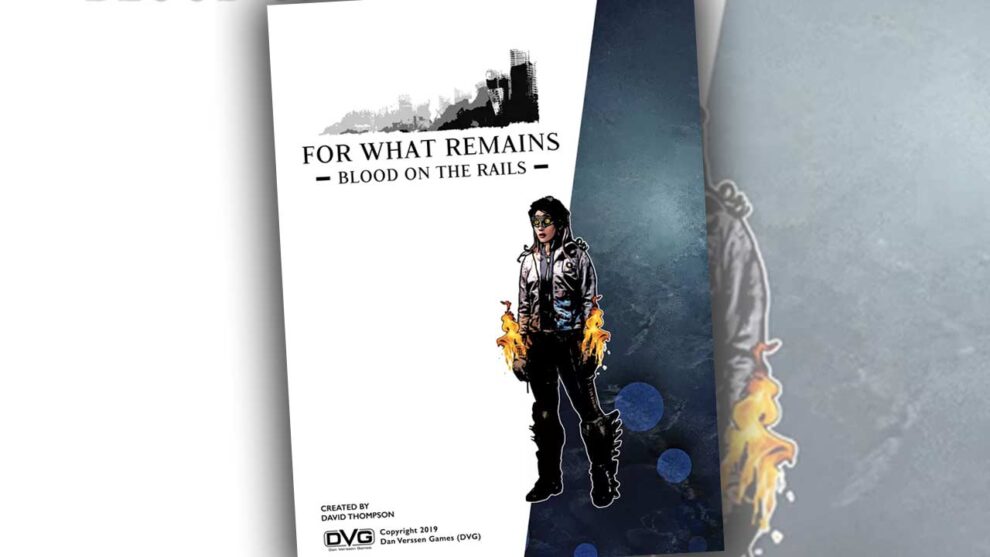

I spent a weekend afternoon playing For What Remains: Blood on the Rails at the board game café where I work. My friend Nathan and I convened to do so. My review copy, kindly furnished by Dan Verssen Games, had been sitting on my shelf for a few months. Finding the time and the volunteer for a two-player skirmish game isn’t always the easiest thing.

I was excited. I’d never played a skirmish game before, despite having designed the rules for one in middle school. If the word “skirmish” in this context is new to you, skirmish games are smaller-scale wargames centered around the management of individual units. There are plenty of wargames in which massive battles are reduced to a few cardboard chits. I push one cardboard square labeled “Army of the Potomac” onto Maryland, you push another cardboard square labeled “Army of Northern Virginia” onto Maryland, and we agree that that was the Battle of Antietam.

Skirmish games take the opposite approach. You control every soldier individually, deciding where they move and whom they engage. If you’ve ever seen anyone play Warhammer, that’s the right idea. Though the scale involved in full games of Warhammer 40K moves it away from the more contained types of fights we see in skirmish games, Warhammer has several skirmish variants.

Skirmish games aim to cut out the massive time burden that comes with a Warhammer, the dozens of necessary units and the tome(s) of rules. Skirmish games have streamlined rule sets, require fewer soldiers, and don’t take nearly as long to play. They are perfect for toe dipping, which is exactly what Nathan and I were doing.

For What Remains takes that approach further than most. This is a fully self-contained skirmish game. Everything you need comes ready in the box. The only prep you need to do involves punching out cardboard and reading the rulebook. What does this skirmish game think it is, a board game?

Troops on the Field

Each player must first choose their army. There are six in the world of For What Remains, with two included in each set. The factions handle quite differently, with abilities and units that emphasize certain play styles. Blood on the Rails includes ECHO, a paramilitary group with telekinetic powers, and the Soldiers of Light (SoL), a group of religious fanatics who use trained beasts in combat. It’s a great pairing. ECHO requires a bit more finesse to get right, but their preference for keeping their distance while using ESP to attack plays nicely against SoL’s unwavering commitment to keeping you as physically close as possible.

The next step is probably the most important part of the game. Each army has more unit types than you can play in a single encounter. You have to choose who you want to bring into the field, and, furthermore, at what level. Each unit has a variety of stats to consider, such as movement, attack range, and so on, combined with their abilities, and those are all affected by unit level. To keep you from simply playing the strongest soldiers, For What Remains uses a points system. The more powerful the unit, the more points it costs. Your entire army has to come in under the points budget for the game. This forces you to diversify.

The final bit of setup before deploying your units is creating the terrain. I know that sounds dull, but it’s really wonderful. The terrain consists of a 3×3 grid of double-sided tiles, each with varying arrangements of high and low spaces, of coverage or wide open expanses. Every tile placed is a threat, or a promise, or an acknowledgement. Different terrain types facilitate different styles of play, and this part of the game only gets better with familiarity.

Pull

In retrospect, it was silly for me to have worried about the overhead involved in Blood on the Rails, since the For What Remains system was designed by David Thompson. Thompson, of Undaunted, War Chest, and Valiant Defense fame, has a remarkable gift for boiling designs down to the bare minimum of rules while maintaining thematic fidelity and astonishing narrative capacity. I’ll say this: if you’ve played War Chest or Undaunted, you are closer to playing For What Remains than you might expect.

Each unit is represented by three chips. Each round begins with both players secretly choosing five of the chips they have available, and adding them to the draw bag. Chips are drawn one at a time, and activate the corresponding unit. At that point, you can execute an action. This is an extremely familiar mechanism for anyone who’s played a David Thompson game, and I don’t mind one bit. It’s his signature mechanic because it’s a great mechanic.

Experientially, the chip pull makes the game dynamic and dramatic. Mechanically, the chip pull makes the game more tactical by preventing perfect planning. With just the right (or wrong) pull, your opponent has the ability to short-circuit your designs. In my second game, I managed to snag victory from the jaws of defeat with a lucky chip pull. I got lucky, there’s no question, but the reason Thompson’s games sing can be reduced down to a single question:

Was it really luck?

An absurd question. Of course it was luck. My opponent had me one good combat roll away from oblivion. But for that chip pull, I was done. On the other hand, three of the chips I put in that bag were for that particular unit. I saw the opening on the previous turn, and elected not to use that unit while I pushed in a different area of the board, which did three things:

- It created the circumstances necessary to get me one point away from winning.

- It drew my opponent’s attention away from the opening I’d seen until it was too late.

- It freed up all of my chips so that there was a 40% chance the pull would be what I needed.

In a game where the odds of any one chip being the first chip start at 10%, that’s huge. This is the genius of Thompson’s games, the reason that his highly chance-dependent designs don’t feel like the result of nothing but luck. Luck in a David Thompson game is earned. It precipitates as a consequence of your good choices.

For What Remains is tense, streamlined skirmishy goodness. It’s a wonderful entrée into the world of skirmish games, with approachable rules and an easy start. Your choices matter, the board state is dynamic and exciting, and the various abilities offer an incredible amount of both variety and depth.

Nathan and I played several games in a row. We loved it. We spent about half an hour afterwards flipping through the rules online for the other factions. During play, an endless stream of Warhammer players would stop by the table to ask what we were playing. Several of them expressed an interest in playing.

In the world of skirmish games, that’s the ultimate endorsement.

Agreed! My oldest son likened the For What Remains system to the X-Com computer game… which I can see.

I’ll note the game also has both a solid campaign system AND a very good solo system.

There exists a time when this game would have been my jam; but this is the sort of game my social circle would not even think to give two looks before saying ‘no.’

It looks cool. I think I would like it. If I purchased a copy, it would do little more than gather dust.

Thanks for a great review.