Pavlov’s House, the first entry in David Thompson’s now-venerable Valiant Defense series of solo tower defense games, is punishing. That’s putting it mildly. The terms of my contract with Meeple Mountain prevent me from using more accurate, more colorful language. I lost my first game handily, and that was with three or four rules errors working in my favor.

Pavlov’s House puts you in charge of the Soviet soldiers who held off a German siege of the titular apartment building during the battle for Stalingrad. Each round consists of three phases, working from right to left across the trifurcated board. You start in the area surrounding the Volga, which runs through the city. Here you will attempt to set up communications networks, ready anti-aircraft and artillery, and send both troops and supplies to the house.

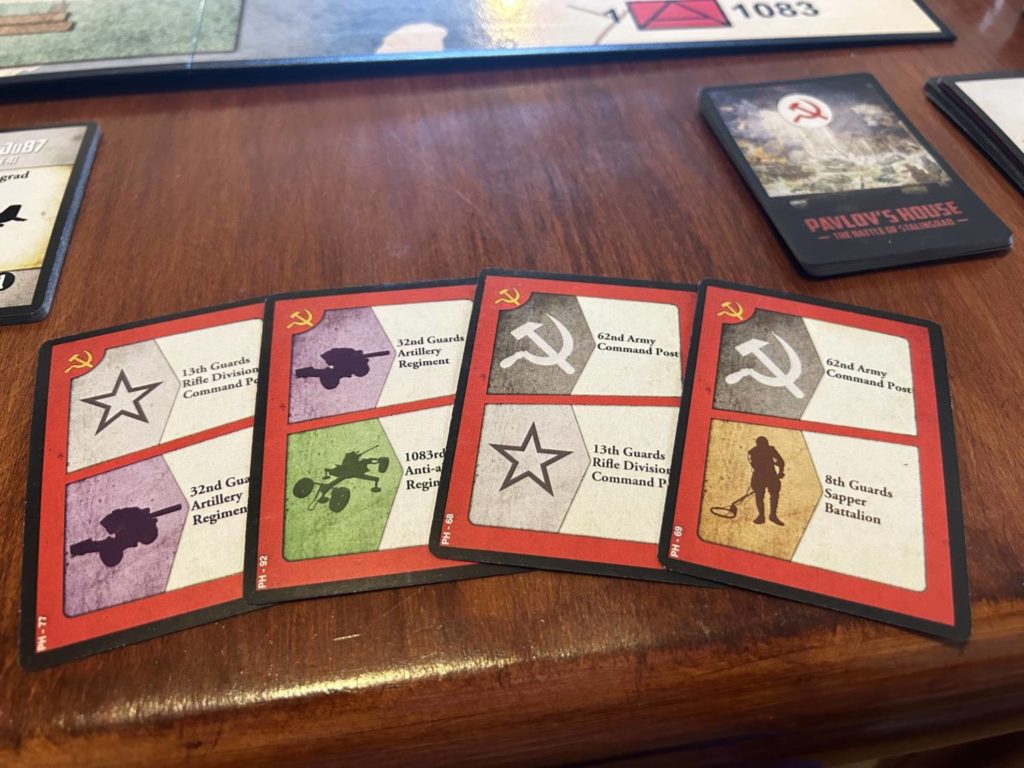

This is all managed by a simple but tense card system. You draw four Soviet cards, each of which features a random two out of eight possible actions, then choose three. You get to perform one action per card you play. You quickly reach a point where these choices are agonizing, where there are things you want to do being balanced against things you know, for the sake of the mission, you have to do.

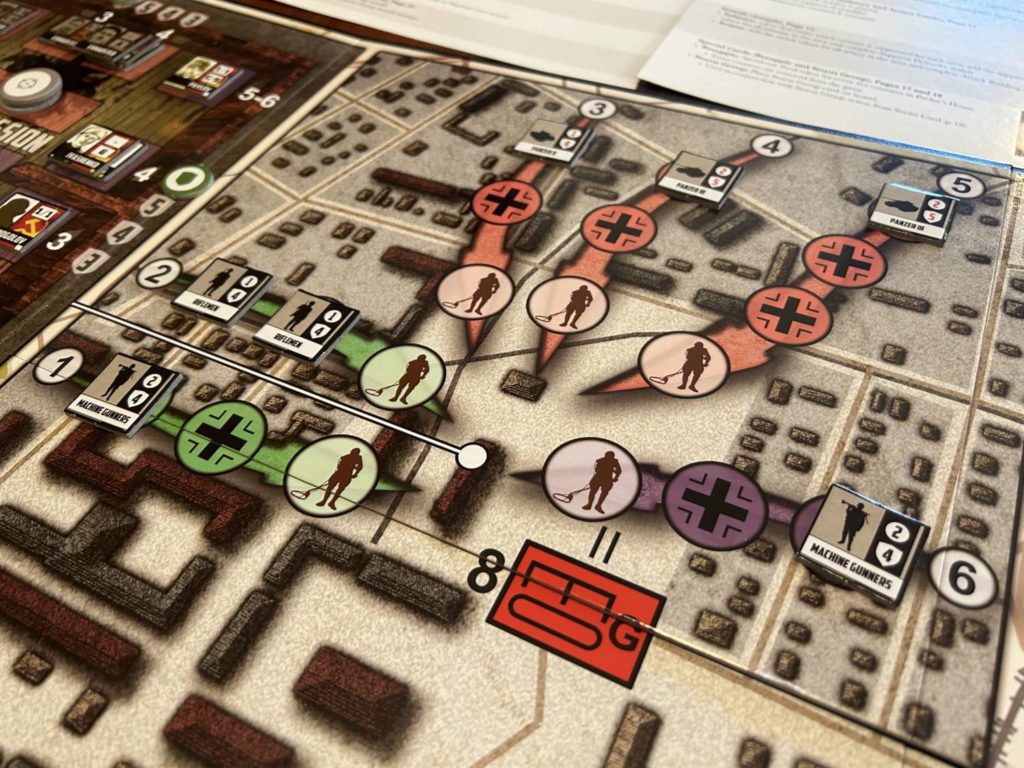

The agony is cranked up by Wehrmacht military interference, which takes place during the second phase. Draw three Wehrmacht cards and resolve their effects. Artillery fires on the house, damaging the structure and making it easier to wound your troops. Bombers disrupt your ability to perform actions during the first phase. The middle section of the board shows 9 January Square, where Pavlov’s House was located, and many Wehrmacht cards advance infantry and armored divisions on the paths toward the house.

The third section of the board is the interior of Pavlov’s House itself. Here, in the third phase, you move troops around and use actions in a bid to prevent the Wehrmacht from taking the house. You can Exhaust soldiers to Suppress, helping to slow the encroaching Germans, or Attack, which removes tokens from the board. You choose a target and roll a die, hoping to hit or exceed their Defense value. While dice combat isn’t for everyone, it has always been my experience that Thompson exceeds in creating decision spaces where you have a good sense of the odds. They aren’t always in your favor, but you know what is and isn’t a last-ditch effort.

This is the sweatiest portion of the game, where you constantly find yourself wishing for one more action. Each time you use a soldier, you’ll need to spend another action later to ready them for more combat.

If a German token makes it to the house, you lose. If at any point you run out of troops, you lose. If the Command Post for the 62nd Army gets bombed twice, you lose. If, on the other hand, you make it to the end of the Wehrmacht deck without any of that happening, you win.

Whose House?

I have nothing but glowing things to say about most David Thompson designs, and Pavlov’s House is no exception. Of the three Valiant Defense titles I’ve played, it is far and away my favorite. It doesn’t quite unseat Comanchería as my favorite solo experience, but it’s close. After my first game, I spent three days thinking about how I could have set myself up differently in the early game. You are constantly faced with tough decisions. The potential benefits and drawbacks of each choice are readily apparent, rather than buried beneath layers of rules grit. The Wehrmacht opponent is simple to operate, so playtime is focused on your own choices.

Between my recent plays of Pavlov’s House, Lanzerath Ridge, Resist!, Undaunted: Stalingrad, For What Remains, and War Chest, I’ve spent a lot of time considering Thompson as a designer. I didn’t even realize, until typing that list out, how many of his games I’ve been playing recently. He has a proclivity for certain kinds of settings, of course, and certain mechanisms, but that’s true of many designers. What separates him from the rest of the pack, I think, is his gift for narrative.

We talk about thematicism a lot in this hobby. For the most part, we seem to relegate it to a matter of rules integrity. Does each rule make sense for the setting of the game? Even the most “thematic” games don’t usually feel all that narratively-driven to me. In broad strokes, perhaps, but they aren’t evocative. Thompson’s designs are heavily evocative. I smell the gunpowder. I picture the soldiers sprinting across the room and grabbing their rifles. I feel the thrill and release of a desperate gambit paying off.

The only designs that consistently manage similar levels of immersion, in my experience, are Mage Knight, Root, and John Company, games with significantly heavier rules sets. Together with War Chest, Pavlov’s House was the design that put Thompson on the map. It’s easy to see why. The board gaming landscape has been all richer for having him there.

If the analog version of Pavlov’s House isn’t your speed, check out our review of Pavlov’s House Digital.

Add Comment