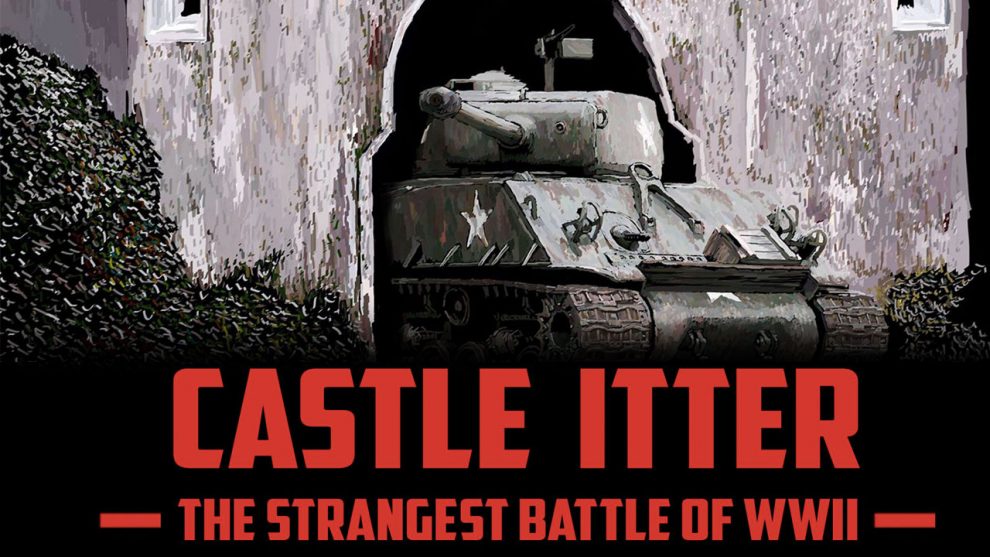

On May 5, 1945, in the waning days of World War II, U.S. Soldiers from the 142nd Infantry Division joined forces with French prisoners of war, Major Josef Gangl, the remains of his Wehrmacht unit, and an Austrian freedom fighter to defend Castle Itter from the advancing 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division. Castle Itter, the second solo Valiant Defense title from designer David Thompson and publisher DVG, has the player lead efforts to defend that castle until the arrival of American reinforcements.

So early in the review, and I can already hear fidgeting in the seats. “I’m here to have fun, not to learn history!” “This sounds an awful lot like a war game.” “A solo game? Poppycock!” My fellow citizens, I understand your concerns. If you are into contemporary warfare as a theme and/or you are an avid solo gamer, you’re already excited. If you aren’t, let me tell you upfront that I actively dislike contemporary warfare as a theme, and while I’m often happy to play a solo game, it’s seldom my first choice. Hear me when I tell you that Castle Itter transcends both of those caveats.

Gameplay

The turn structure is wondrously simple, especially given how satisfying the decision space is. You use five actions each turn to place, move, refresh, or fire with the chimerical forces at your disposal. After that, three cards are revealed from the top of the enemy deck, and the corresponding actions are carried out. These primarily include troop placement and artillery fire, the specifics of which are determined by dramatic and increasingly sweaty rolls of the dice.

The action economy is perfectly calibrated to keep the game tense while rewarding careful and intentional play. Each turn is spent addressing the largest fires while setting the table for dealing with those that seem to be growing. There are various abilities different pieces have at their disposal that make careful troop placement critical and, more importantly, a blast. Getting your troops set out in a way that makes the most of everyone’s abilities is deeply satisfying.

That said, of course, the game would become tiresome if you could set everything in its right place and function on autopilot. Castle Itter does not allow for complacency. The various sections of the castle will come under heavy fire. Those that get damaged will leave the troops inside vulnerable. Those Nazis are relentless, and the moment you feel like you have everything just so, the rug gets torn out from under you.

The game can end in three ways. It is an immediate loss if Panzergrenadier troops ever make it all the way to the castle, and it goes to scoring if you survive the assault, either by making it to the end of the enemy deck or by revealing the 142nd Infantry card, which is shuffled into the deck via a mechanism I’ll return to in a minute.

War Games: A Consideration

I have been taking a bit of a deep dive into historical board games recently. I love historical themes, especially when designers engage with them thoughtfully. Nothing delights me more than a game design that translates real world events into in-game mechanics. I first caught the bug when I played Comanchería over Christmas and a card that corresponded to the arrival of French fur trappers in the southeast United States allowed me to trade at any location along a river. When I received my review copy of Red Flag Over Paris a few months ago, I happily spent an hour or two poring over the historical notes in the back of the rule book, especially the part that went through every card, one by one, explaining who the people or what the events were. I was delighted to the point of genuine glee by the ways in which the historical background for each card lined up with its in-game effect. I find that sort of thing incredibly cool.

I appreciate that I am an outlier here.

Given that war provides the backdrop for so many historical games, I have also been doing a bit of a deep dive into war board games. These I do not care for so much. For one thing, the theme just doesn’t interest me. My beloved Undaunted (another David Thompson design) and Air, Land, and Sea are two of the best games in my collection, but they don’t get played anywhere near as much as they would if they had different themes. War isn’t a sandbox that inspires me to play.

I’m also not a fan of the ways in which most war-themed board games abstract the very real loss of life that comes with warfare. I don’t begrudge other people their participation in the niche. I don’t find it inherently problematic, it’s just broadly not for me, this subgenre where you are God enough that losing real human troops is merely experienced as a tactical inconvenience. Thompson is noteworthy for the ways in which his games address the dispassion and distancing. Most of your troops have individual names. When they die, you feel not only the loss, but the responsibility.

In one game, the American tank Besotten Jenny was taking heavy artillery fire. In a key moment, I decided to have the crew inside lay down one last round of suppressive fire before evacuating. I knew this would delay their departure by several rounds, but the threat of pressure from the east was too high. I couldn’t pass up the tactical advantage.

Before I could get Rushford, Seiner, and Szymczyk out, Besotten Jenny was destroyed. All three were killed. I remain surprised by the level of guilt and sadness that I felt. I spent a good thirty seconds to a minute sat at the table, feeling culpable for the loss of these three cardboard lives. It even compelled me to do some research on the real life crewmen. I was relieved to find that my outcome was untrue to history. When Jenny was wrecked, only one soldier was inside, and he escaped uninjured.

Maybe the Most Dramatic Bit of Storytelling I’ve Ever Experienced in a Game

Let me tell you about French tennis star Jean Borotra.

Jean Laurent Robert Borotra dominated tennis in the 1920s and 30s. He was, for a time, ranked as the no. 1 player in the world. Borotra was a member of the Parti social français, and was responsible for leading the Révolution nationale’s efforts in sports policies during World War II, whatever that means. For this, he was arrested by the Gestapo in 1942 and ultimately taken to Castle Itter, where he was held through 1945. During the battle for Castle Itter, Borotra offered to vault the fortress walls and run through enemy lines to request reinforcements from a nearby town. Remarkably, he succeeded. More troops from the 142nd Infantry arrived at around 16:00 hours, ending the siege.

In Castle Itter, Borotra is one of five included French prisoners of war. His piece, and his piece alone, has the Escape action. In order to Escape, Borotra has to be positioned on a space that corresponds to a cleared out section of the board. If, at the start of his action, there are no enemy soldiers in the matching area, he vaults over the wall and runs into town. At that point, the player shuffles the 142nd Infantry card into the last few cards of the enemy deck. The earlier in the game he escapes, the earlier the card might get drawn.

This is exactly the kind of mechanism I love. It’s wonderful for design, strategic, and narrative reasons. By nature of the number of spaces on the board, you’ll end up with troops stationed in the positions facing low numbers of enemies. Clearing the way for Borotra to escape gives them purpose. It would be easy for a game like this to become repetitive. Engineering Borotra’s escape gives you a specific mid-game goal. Narratively, it creates both a point of tension and a split in time. If Borotra gets taken out by an enemy sniper before he has the chance to escape, or if the enemy proves too difficult to suppress, the reinforcements will never come.

In my most recent game of Itter, I was having a difficult time getting Borotra well-positioned. To be entirely honest, I was probably overly-focused on getting the Frenchman set up to escape. It isn’t necessary to do so to win, but I was dead set on pulling it off. I finally cleared a channel only to realize that I had miscalculated. One enemy soldier I’d thought was in a different section was in fact blocking Borotra’s way. All of the troops who could help were either exhausted or in other sections, meaning it would be another two or three rounds before I could try again. By then, it may have been too late. I ended my turn distraught.

I flipped over the first enemy card. I dutifully placed yet another troop in the section I’d thought I’d cleared out. I flipped over the second. It was artillery fire. I flipped over the third. It was the reinforcements card, the only piece of good news that starts the game in the entire enemy deck. I was granted access to three additional troops, including Austrian freedom fighter Hans Waltl, who in real life joined the efforts to save the castle mid-fight.

I had two spaces open that looked out over the area through which Borotra was trying to make his escape. In a last-ditch, desperate effort, I placed Waltl down and had him open fire on one of the enemy troops. I rolled the die and yelped when I rolled a four, sufficient to remove the Nazi rifleman. I placed another of the reinforcements in the second space, rolled the die, and screamed the loudest I have ever screamed at a board game. It was a five. Borotra’s path was cleared. He escaped.

I felt like I was watching an incredible action movie. Just when all hope seemed lost, the good guys managed to pull off a win. It is the most narratively evocative experience I’ve ever had playing a board game.

In Conclusion

Castle Itter is the second Valiant Defense title, but it is my understanding that it was the first to be designed. I have heard more than once that Pavlov’s House and Soldiers in Postmen’s Uniforms, the other released designs in the series, are somewhat more complex, and have more nuanced decisions and sources of tension. I look forward to finding out for myself. As of writing this, I have already secured a copy of Pavlov’s House.

Castle Itter is a great, satisfying solo game. It plays in about an hour, and the rules are easy to learn. If you are considering getting into war games, I think it’s a great place to start. It has a significantly lower rules overhead, but the kinds of rules it has, and the way the system works, give you a taste of what you may find further down that path. I can’t wait to play it again. This time, I’m not going to let Rushford, Seiner, and Szymczyk down.

Add Comment