In 2012, first-time game designer Rikki Tahta released a game called Coup. This free-for-all bluffing game has one goal: be the last one standing. On your turn, you pick a single action, such as attacking another player, stealing their money, or grabbing a coin from the bank. To carry out these actions you must hold a card that allows you to carry them out, at least in theory. However, you do not have to show your cards as long as nobody challenges you, and once you get hit twice either by attacks or failed challenges, you are out. The game was, at the very least, an amusing diversion that didn’t hog the table.

Why the brief history of Coup? Captain’s Gambit has an umbilical cord connecting to Coup that cannot be severed. Simply put, without Coup, Captain’s Gambit wouldn’t exist.

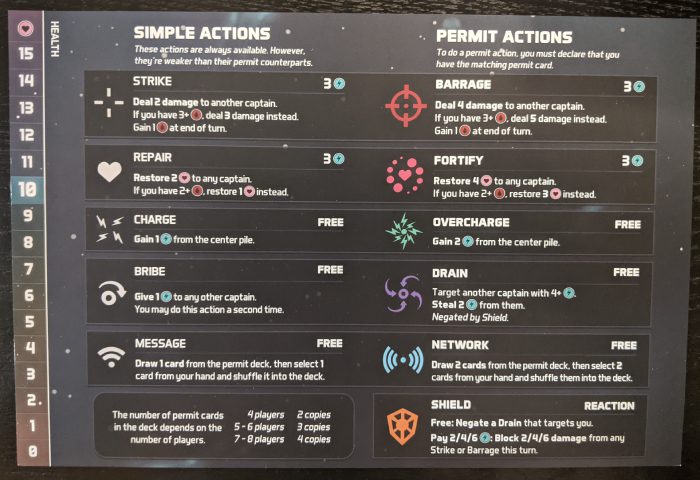

Even the flow of the game is dripping with Coup’s inspiration. You still have your two cards and can challenge other players. When it is your turn, you pick an action, but with 11 actions instead of 8. You can give your energy, the currency of this game, to another player or heal them. In contrast to Coup, this game has health, which gives you a bit more breathing room when you make mistakes. There are also Bloodlust tokens you earn when you attack other players, which can alter future actions.

The concept sounds interesting, but not enough to differentiate it from its roots, so what’s the deal? Captain cards.

Live long, and prosper

At the start of the game, everyone gets a Captain card you don’t show to anyone else. This Captain is your goal of the game. Complete it, and you win. However, if it is impossible to complete your goal, you die immediately. Yes, this means that there can be a domino effect.

This presents a dilemma because the Captains have different motivations. Some want to attack their foes, while others need to survive up to a certain point. Captains may also secretly ally with another player, filling in a supporting role.

Like any other social deduction game, there is a prologue night where everyone will close their eyes, and some Captains might wake up to mess up the situation. Romero and Juliet will acknowledge each other, and they want to eliminate everyone else. Hamlet will drop a Bloodlust token into his target’s palm, signaling that he wishes to kill that player. Cordelia will then place a blue Loyalty token in front of a player, and she wants that player to win. Brutus does the same thing, except he wants to kill their target. Wait a minute…these are Shakespeare characters. I think I need to watch my back around these parts.

A welcoming space

I will admit that when I first read about this, I was getting goosebumps. Experience has taught me that games involving multiple mechanisms like this can have a rulebook that isn’t clear about their interactions. Anyone who has played a game published by Fantasy Flight Games knows where I am getting at.

There’s no need to worry about that here. When you open the tiny little box, you will find two rulebooks inside. One explains the game flow, while the other is an appendix with details on the game’s rules. Some people dislike this because they feel it is as redundant as a college student using Viagra, but it has a purpose. Considering I annoy people within a fifty-mile radius with my rules nonsense, it’s nice that I can find the information I need quickly without disrupting the game too much. Furthermore, this is one of the best rulebooks I have read in a long time. Not only does it explain the game well, but the appendix answers questions I didn’t get a chance to ask.

It’s not just the rulebook that makes it easy to get started. All players have a player mat that lays out their available actions and deck composition. Also included are player aids that show all the Captains and their goals. As if that wasn’t enough, Captain’s Gambit even comes with cardboard tokens that remind you which captains could be in the game and can mark other players.

While I know it’s strange to talk about rulebooks and player aids, I wish more publishers would do this. Whenever I am excited about a new game, I want to introduce it to everyone as if I had just adopted a puppy. Having components support my teaching and be less intimidating makes me want to throw the game into my bag when I go to my meetups.

Toaster tactics

What’s funny about this is the simplicity is merely a deception of things to come. Getting into the game is easy. Getting out is another story. Once you dig in, you have little urge to look back.

One can look at Lady Macbeth. She is a brain in a jar, and if there is one thing science fiction has taught me, you never trust a brain in a jar. Her goal is to collect three Bloodlust tokens and reveal herself. Once she reveals herself, she only needs to survive for one round to win. Sounds easy. Attack three times, reveal, and survive. Alright, so you do that, only to find yourself thrown into the nearest space wood chipper by the other Captains. Ouch.

Let’s moonwalk this situation back for a bit. You’re Lady Macbeth, and you need some bodies on this ship before you reveal, since corpses will have a hard time attacking you. There is also the issue with Portia and Iago. Portia’s goal is to eliminate the player with the most Bloodlust tokens, and you look like a candidate. Iago needs to stay alive and have the most Bloodlust tokens at the end of the game, and you are getting in the way. Hamlet might be another concern since any player can claim to be marked by him, and their death is Hamlet’s victory.

Mingled goals don’t just apply to aggressive Captains. The fun also extends to supportive Captains like Cordelia. As Cordelia, your goal is to make the player marked by your blue Loyalty token win, and you don’t need to be alive to claim victory. The problem here is you do not know what they want, and you have to pinch this information out of them without being obvious about it. Each Captain also has different needs. What if you marked Romero or Juliet? Their goal is to kill everyone while making sure neither of them dies, so helping them involves your death.

I’ve got another one for you if you find that silly. Imagine that Cordelia had marked Brutus and Brutus had marked Cordelia. A killing blow on Cordelia must be delivered by Brutus in order for them to win. They both die if either is killed in any other way. Best part? At the beginning of the game, neither of them nor the others would know this. This is something that the group has to figure out by themselves. Brilliant.

Communal violence

Because of these Captains and their interwoven relationships, you follow a bread crumb trail that doesn’t end. You start trying your best to figure who the other pieces are while avoiding being someone’s pawn. Mind you, I’m only talking about the Captains and their goals. We still need to look at the play-by-play of the game.

Your turn begins with an Energy token as part of your income, and then you choose your action. Most of the actions don’t require any payment, but they won’t help you achieve your goals in the long run. When you perform valuable actions like attacking, healing, or shielding, you must spend energy. Although it seems like an understandable concept, the problem is that you only have 12 rounds to reach your goal.

At first, this might seem like a way to force players to be proactive, but it goes beyond those impressions. You’ll realize quickly that your limited income and the cost of your actions leaves you in a restrained position. If you attack someone, you can’t heal or shield yourself. Almost everything has an opportunity cost, and to fulfill your Captain’s ambitions, you need to take a role in this violent community and talk.

This talk means accusations, collaborations, promises, alliances, and threats. As the round number ticks towards twelve, these discussions will fumble around the table like a greasy football. Players who were allies one or two rounds ago might end up being bitter rivals or ignore each other’s needs, while three players who didn’t exchange words all game will suddenly talk about a new opportunity for them to exploit. In other words, Shakespeare.

Believing the lie

Another point to consider is the challenges. Like Coup, you can challenge another player when they declare an action. If they show they have the card, you lose the challenge, and they need to draw a new card while discarding the old one. Considering it only takes two hits to be eliminated in Coup, the risk of challenging another player was too high. In Captain’s Gambit, you start with 10 health, and the challenge puts 3 health at stake. (Remember, healing is an action in this game.)

Because of this setup, Captain’s Gambit encourages you to call people out, when you think they are lying or to force them to throw away the card they are holding. It was amusing to look at my friend straight in the eyes and challenge her, even though I know she is telling the truth, for the sake of discarding that Drain card.

The most surprising part of my sessions with Captain’s Gambit was player elimination. Players eliminating each other is one of the cardinal sins of board game design, right up there with rolling to move, but it isn’t an issue here. A game of Captain’s Gambit can end after one elimination, and the dead can talk freely, which fits right in with Shakespeare using superstition in his plays. Even if that weren’t the case, rounds go faster as each new corpse gets thrown out of the airlock. Not only that, but you become emotionally and intellectually invested in this drama. You want to see the conclusion of this story and to confirm your suspicions. A lot of games get player elimination wrong, but Captain’s Gambit gets it right.

Closing the hatch

One of my core tenets for board game reviews is to decipher the designer’s intentions. My goal is to evaluate their tools and determine what type of experience they intend to give players. Captain’s Gambit obviously wants to be a better Coup, and from that standpoint, it delivers without flaw. Unlike the door panels of my car, everything here aligns perfectly. The effects of your actions and their energy costs are just right. Despite the cast of 19 Captains, none of them feel overpowered or underpowered. Come to think of it, I do not have a favorite Captain since I view each Captain as an opportunity to screw my friends.

Honestly, if I had to nitpick one thing, it’d be the player mats — specifically, the health tracker. Tracking your health does not involve tokens. Instead, there’s a plastic tab you pin to the side of the player mat, making the situation hard to read. It’s an understandable component compromise, given that this game didn’t exactly create an explosion on Kickstarter, and it comes with two helpful rulebooks.

At this point, I might as well throw away my Game Critic badge into the nearest garbage bin. I could continue on by mentioning Captains such as King Lear and Othello changing the game by introducing blue Loyalty tokens as a new currency. I would have liked to say more about the excellent character design of each Captain, but I think I have made my point. Anyone interested in bluffing and social deductions, especially if they enjoyed Coup, should spend their time on this one if the opportunity arises. Time is the most scarce asset you have since it is something you’ll never get back, and I’ll gladly spend some of that time on Captain’s Gambit.

Sounds like a great upgrade to Coup. I’ll definitely try this one out when I have the chance!