There is an old saying: “When the cat’s away, the mice will play”. Never was this more true than when King Richard was captured while away on a crusade. Rather than kill him outright his captors, sensing an opportunity, demanded a literal king’s ransom for his return. Rather than pay the King’s abductors or even attempt any kind of rescue, the King’s brother John decided to seize power for himself. Mouse indeed! More like a rat!

You stood by and watched as John wielded his ill-begotten power in the worst ways imaginable feeling powerless to do anything about it. When your father died while off fighting for King and country that all changed. John, the self-titled ‘Sheriff of Nottingham’, came knocking at your door. Your land, your home: he took it all. Everything your father left to you, gone.

This would not stand. Something had to be done.

Overview

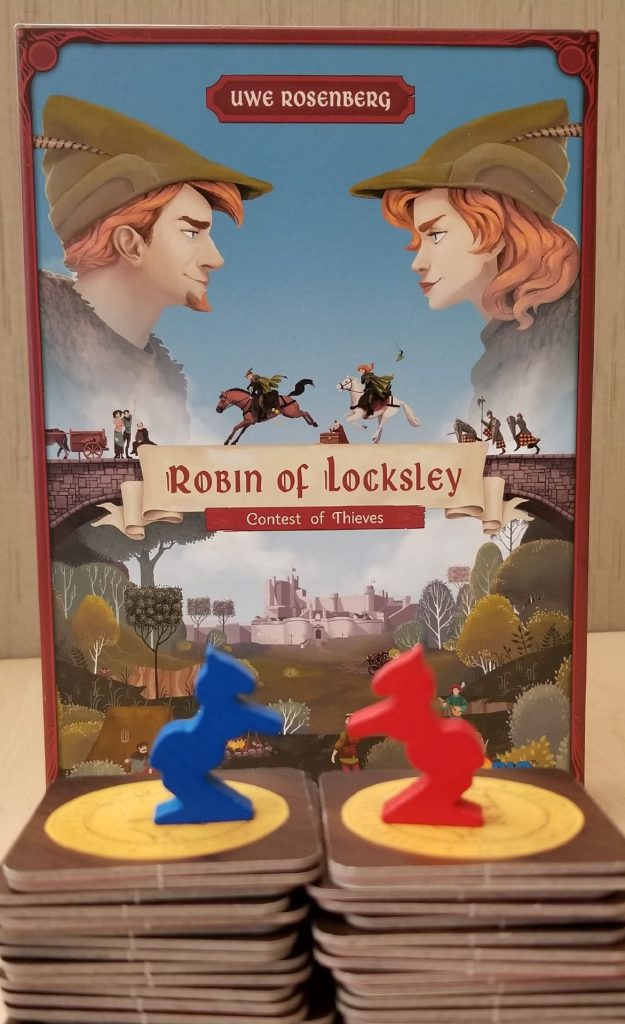

In Robin of Locksley the players take on the roles of one of the two Locksley heirs as they steal loot from the Sheriff’s holdings to pay King Richard’s ransom. In between the players sits the game board which consists of 23 square tiles depicting different types of loot in a 5 x 5 formation. Two of the spots where tiles would sit are taken up by the players’ Robin pawns. During the course of the game the players will be moving their Robins around this area and collecting Loot tiles.

Surrounding these tiles is a border composed of small rectangular Fame tiles bearing text and iconography. At the beginning of the string of tiles sits the players’ Bard pawns. The outer tiles dictate what the players will need to achieve in order to move their Bard pawns around the outer rim of the play area. For instance, a tile might dictate that in order to move your Bard pawn onto it you must possess 1 blue, 1 green, and 1 red piece of loot.

If one player completes the circuit around the outer rim twice before the other player or if they manage to lap the other player then they win the game. King Richard, upon his return, is so impressed by their dedication to his cause that he rewards them handsomely. Presumably they become the new Sheriff of Nottingham.

This is a high level overview of the game and if you are just interested in reading what I think, feel free to skip ahead to the Thoughts section. If you’d like to know more about how to play Robin of Locksley, then continue reading.

Limbering Up: the Preparation

To begin the setup for Robin of Locksley, the 60 Loot tiles are shuffled into a face-down pile so that the coin icon on their backs is showing. Then 25 of these are drawn and arranged face up in a 5 x 5 grid. Next, a starting player is chosen and takes a Loot tile from any corner, places it face-down (coin side up) in front of them, and places their Robin pawn into the now empty spot. Their opponent does the same thing in the opposite corner.

Now that each player has placed their Robin pawns and has a Loot tile, the Fame tiles are arranged along the outer edge of the playing area. First, the “The Beginning” corner piece is situated on a corner and 3 more randomly drawn corner pieces are placed at the other corners*. Between each of these corner pieces are placed an equal number of the smaller Fame tiles. For a shorter game, only 2 Fame tiles should be used between each corner. For longer games, you can use between 3 or 4. Just above the “The Beginning” Fame tile should be placed the “Long Live the King” Fame tile. Directly beside this is where the players will place their Bard pawns. When everything’s set up, it should look something like this:

Nimble Fingered: the Acquisition of Loot

Your turn is split into two parts: Robin movement and Bard movement. Moving your Robin is easy once you get the hang of it. Your Robin moves in an ‘L’ shape similar to the way that a Knight moves in a game of chess: 2 tiles in a single direction, then 1 tile to the side or 1 tile in either direction, then 2 tiles to the side. The Robin pawn may never leave the inner area and may never occupy the same space as the opponent’s Robin pawn. Once you’ve moved your Robin pawn, then you collect the Loot tile you landed on and draw another from the face-down pile and place it face up into the space that you just left.

Fleet Footed: the Race Around the Board

In the second part of your turn you will be moving your Bard along the Fame tiles if you’re able to meet the required conditions to do so. To determine whether or not you are able to move your Bard pawn, you’ll look at the next Fame tile in clockwise order from where your Bard pawn currently sits to see what the criteria listed on that tile is. If you meet those conditions (possess 1 green Fame tile, for instance), then your Bard pawn advances to that tile. If you happen to meet the next condition (end your Robin pawn movement in a corner, for example) then you can move to that Fame tile. If you can’t meet the conditions, then you can discard a coin side up Loot tile to the bottom of the face-down Loot tile deck and proceed anyway. You will continue moving in this fashion until you are unable to meet a condition or you decide to end your movement. Then your turn comes to an end and it is the next player’s.

In addition to a player’s Robin and Bard movements, there is one additional action that a player can take at any time during their turn: selling Loot collections. This is how players obtain the coins needed to skip over Fame tiles. A Loot collection is defined as “3 or more Loot tiles of the same type”. When selling a Loot collection, the player must sell all of the Loot tiles of the same type. The first 2 Loot tiles are returned to the supply, but the remaining Loot tiles are flipped over so that the coin side is facing up.

Thoughts

I’m not going to mince words: I really like Robin of Locksley. I like it a lot. That is not surprising to me considering it’s an Uwe Rosenberg game. If I’m being entirely honest with you, I am something of an Uwe Rosenberg fanboy. You could even say I am a little obsessed. He’s just an amazing designer. That is not to say that everything he’s done has been perfect. Take his game Hengist, for example. That game is just a disaster. But not Robin of Locksley. I don’t think he’s put out a purely 2-player game I have enjoyed more since he released Patchwork and Fields of Arle in 2014. So what is it about Robin of Locksley that I like so much? I’m glad you asked.

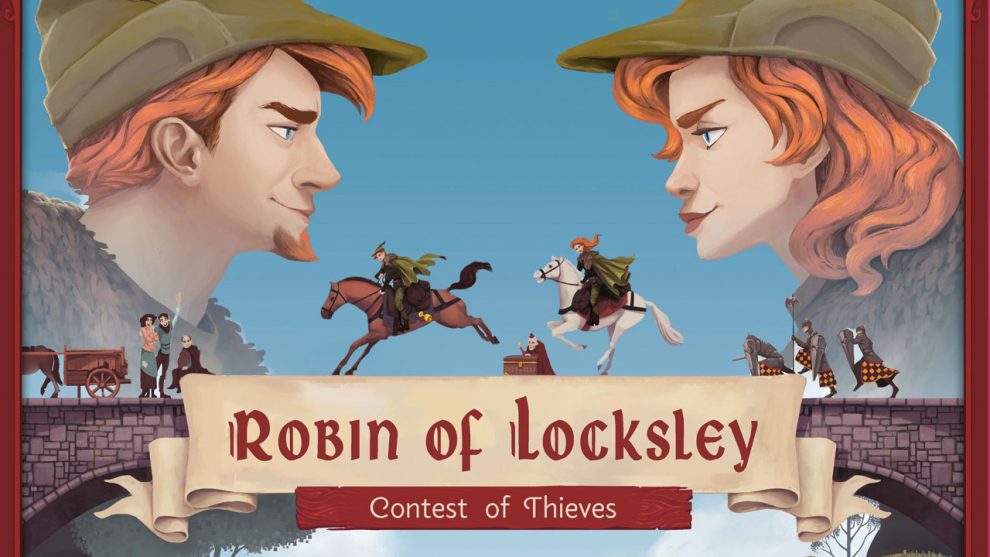

First of all, I like the aesthetics. The artwork on the front of the box sets the mood. We see our heroes fleeing on horseback, saddlebags overflowing with loot, across a bridge, a contingent of the Sheriff’s guards in hot pursuit. Nearby a small group of peasants cheers them on. In the background is an image of the Locksley duo looking at each other, sly smiles on their faces. It is obvious that while disrupting John’s plans is serious business, there’s still a friendly competition at play. And this overall art style has been carried through to the Fame and Loot tiles as well.

The brilliant aesthetics serve as an excellent canvas for some pretty stellar gameplay. While Robin of Locksley looks like a racing game at first blush, it’s really a strategic planning game when you look under the hood. Because all of the Fame tiles are laid out at the start of the game and because you can always survey every Loot tile that is within striking distance of your (and your opponent’s) Robin pawn, you’re able to plot out your moves well in advance. The only real surprises are what your opponent chooses to do and which Loot tiles are turned up into the space that they vacated. Even though the actual game play is simple – move your Robin pawn and take a tile – the choices you are faced with are anything but.

For instance, in my first few games I kept foolishly choosing tiles that left my Robin pawn in locations that allowed my wife to capitalize on position-based Fame tiles. I’d stupidly take a green tile and then my wife would move her Robin pawn to take the tile directly adjacent to my Robin pawn in order to move past the Fame tile that required her to end her move with her pawn directly adjacent to mine. I hadn’t considered how my tile choice would set her up to be able to achieve her objectives. I was too busy trying to figure out how to get my own pawn moved around the track. Now, when we play, my choices are much more deliberate and calculated. I’m not only thinking about my own progress, but I am always trying to calculate how my choices are going to benefit her and how I might capitalize on the choices that she makes.

Robin of Locksley is also one of those games that rewards your efforts with some very satisfying turns. One second you might be five or six Fame tiles behind. Then you come rocketing from behind out of nowhere as all of your planning and Loot tile hoarding comes to fruition. Green tile, check. Blue tile, check. Robin pawn in the corner, check. Red tile, no. But we’ll just sell off this extra green tile and then spend that coin to bypass it. And on and on you go. This is one of my favorite aspects of the game. I love the build up and the exciting climax that moments like these provide and in Robin of Locksley there are plenty of those moments.

Not everything about the game is perfect, though. For starters, there are no plastic bags included in the game so everything just kind of slides around inside of the box. This could have been solved by including a cheap box insert, but there isn’t one of those either. I find it displeasing when a publisher doesn’t include any kind of storage with their games. This isn’t the first time I have groused about this particular topic in a review and I doubt it’ll be my last. My other component issue is that the Fame tiles are all single-sided. I feel like an opportunity was missed here to present even more customization and replayability into the game by not using the other sides of the tiles in some way.

Secondly, I have some issues with the theme. In the classic Robin Hood tales, Robin was a pretty selfless hero. He took from the rich so that he could help the poor. His own status was unimportant to him. In this game, though, his goals aren’t as altruistic. Helping the poor is just a byproduct of his mission to disrupt the Sheriff’s activities to impress the King whenever he returns. That just seems contrary to every Robin Hood tale I have ever heard.

My other issue is with the addition of the other Locksley heir, a construct apparently created out of thin air just to serve the game’s theme. I don’t really have any problems with this per se. I get it. Robin Hood is a fictional character from a fictional universe. Why couldn’t this be how it really all happened? No, my problem with it is that the other Locksley heir is also apparently named Robin. Think about it. Each player is controlling a Robin pawn. The implication is there. The Locksley parents must have been highly amused naming their children the same thing. “Boys can be named Robin and so can girls! We absolutely MUST name them both Robin!” I can just imagine how confusing that must have been growing up. “Robin, get in here and pick up your clothes. No, not you, Robin. I was talking to Robin.”

My biggest issue with the theme, though, is that Robin of Locksley doesn’t really ever make me feel like I am playing a game that has anything to do with Robin Hood at all. In true euro fashion, it feels like the theme was just pasted on after the fact. So if you’re going into a game of Robin of Locksley in the hopes of feeling like you’re right in the middle of the Robin Hood legend, prepare to be disappointed.

Don’t let that dissuade you, though. Robin of Locksley is a really fun game and well worth your time. Like I said earlier, I’m a fan and I think you will be, too.

Pasted on or not, I am a bit of a Robin Hood nut… gonna have to check this one out!

Check out Uwe Rosenberg’s other Robin Hood themed game ‘Nottingham’ while you’re at it. It’s a fantastic game.