Hello and welcome to ‘Focused on Feld’. In my Focused on Feld series of reviews, I am working my way through Stefan Feld’s entire catalogue. Over the years, I have hunted down and collected every title he has ever put out. Needless to say, I’m a fan of his work. I’m such a fan, in fact, that when I noticed there were no active Stefan Feld fan groups on Facebook, I created one of my own.

Today, we’re going to talk about 2019’s Revolution of 1828, his 29th game.

Revolution of 1828

The political theater has never been one of gentlemanly discourse. In any given political race you’re almost guaranteed to hear one candidate bad mouthing another. These days we take it as given. We have to sit through attack ads while we’re watching football. Every newspaper or magazine we open is inundated with mudslinging and character assassination. We’ve grown so used to it that it’s become background noise, easily ignored and dismissed. But that wasn’t always the case. The world used to be a lot bigger. In order to hear a candidate speaking unkindly about another candidate, you had to be there in person or you had to hear about it from another person who heard it from someone else.

In 1828 everything changed. America’s first commercial railroad had just opened for business the year before. The telegraph was just around the corner. The world was growing smaller. On top of that, the current sitting president was very unpopular in some circles. The Election of 1824 had seen Andrew Jackson running against John Quincy Adams and losing even though he’d gained the majority of the electoral votes. By 1828, both sides were very displeased with the other. These underlying tensions coupled with the ability to spread news quickly created a powder keg that was about to explode. The result was a mess like nobody had ever experienced before.

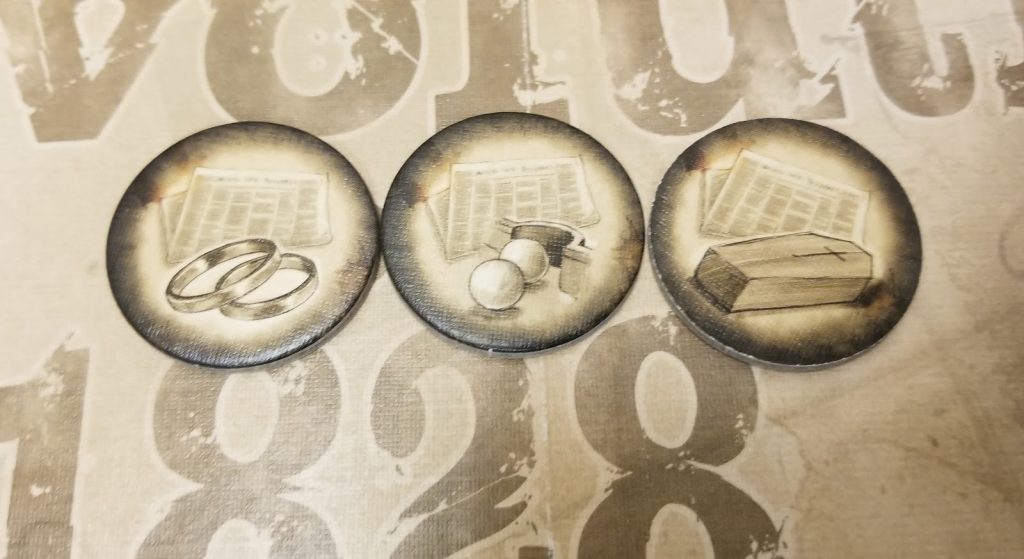

The Election of 1828 was the first true mudslinging campaign. Adams was accused of misusing public funds. The news of the day was that he’d spent the money purchasing gambling equipment when, in reality, it was just a chess board and a pool table. Jackson, on the other hand, was accused of murder. During his time in the military he’d executed a few deserters and he had been known to engage in dueling. He was also branded an adulterer because he and his wife had gotten married in the belief that her divorce from her previous husband had been finalized, but it never had.

That is the setting of Revolution of 1828. It seems an odd choice given Stefan Feld’s past designs (not to mention the fact that he’s from Germany). I’ll discuss the theme in the Thoughts section (which you can skip ahead to if you like), but first an overview of how this two player game is actually played.

Kicking off the Campaign

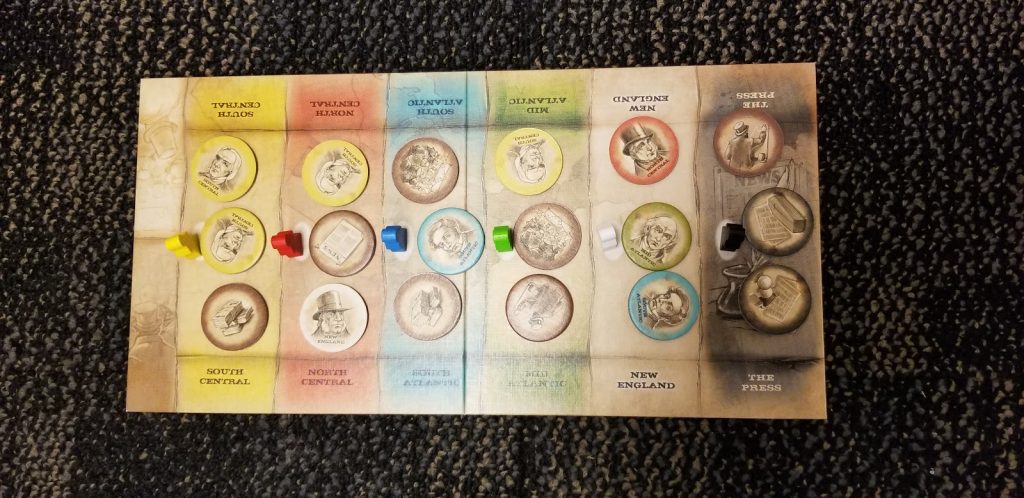

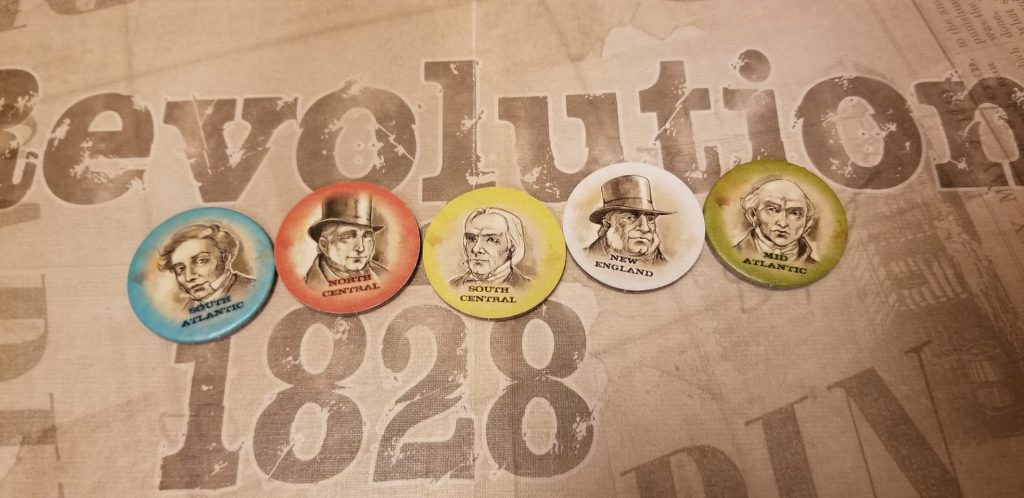

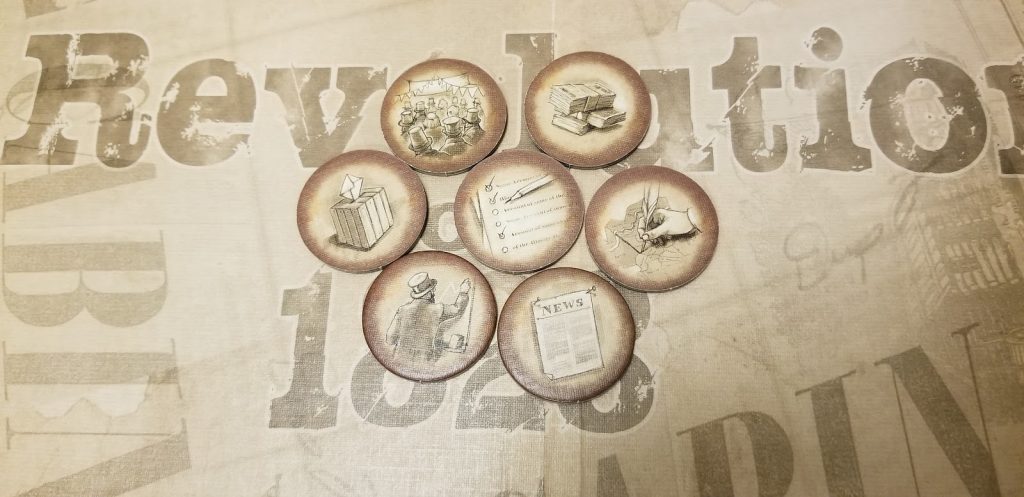

There aren’t a lot of components in Revolution of 1828. There’s a game board that’s divided into different columns representing the different regions of the United States (as well as a column representing The Press) and this is placed between the players. There’s a bag that is filled with rounded tiles that represent the various Delegates, Campaign Actions, and Smear Campaigns that will be utilized by the players in order to earn votes (a.k.a. victory points). After choosing a starting player, that person is handed the bag and tiles are drawn from the bag and randomly placed into the various columns, 3 to a column. The Elector pawns are placed into the appropriate area depending upon the pawn’s color. For instance, the yellow pawn is placed in the yellow column.

Having done all of this, you’re ready to begin.

On the Campaign Trail

Revolution of 1828 is divided into four rounds with the bag of tiles being passed to the other player at the end of each round so that each player will be the start player twice over the course of the game. During each of these rounds, the players will take turns removing one tile at a time from any column of their choosing.

If the removed tile is a Delegate, it is placed in front of the player that removed it next to the matching colored column.

If the removed tile is a Campaign Action, the action is carried out immediately and placed into the Campaign Pile area. Some actions allow you to manipulate collected (or uncollected) Delegate tokens, for instance, while others can be used to manipulate the game state in other ways.

If the removed tile is a Smear Campaign, it acts as a wild card Delegate and can be placed on your side in any colored column of your choice.

If you remove the last tile from a column, two things happen. First, you take control of that column’s Elector (which is important for scoring purposes). Secondly, you get to take an extra turn. If you use that extra turn to remove the last tile from a different column, then you get an extra turn from doing that as well. This can be repeated ad infinitum until removing a tile doesn’t cause the column to become empty.

Counting Up the Votes

Once all of the columns are empty, an end of round scoring occurs. First, the person with the most tiles in their Campaign Pile receives 3 points. Then you look at each separate column. Whoever has the most Delegates of that column’s color will receive 1 vote if their opponent has at least 1 Delegate of that color. Otherwise they receive 2. If each player has the same number of Delegates, neither player receives any votes.

Next, the person with the Elector of that color receives 1 vote for each Delegate they have collected of that color even if they didn’t have the majority. Once all of the colored columns have been appraised, each player collects all of their Smear Campaign tiles and places them into their Press area. If a player has control of the Editor, then they must give their opponent a number of votes equal to the number of Smear Campaign tokens that they have accumulated over the course of the game. For example, consider the following image:

A: Player 2 has collected the most Campaign Action tiles and earns 3 votes.

B: Both players tie in Delegate count and earn 0 votes. Player 2 possesses the yellow Elector and earns 2 votes for their collected Delegates as a result.

C: Player 1 earns 2 votes because Player 2 has 0 red Delegates. They earn an additional vote for their collected Delegate tile since they possess the Elector.

D: Player 2 earns 2 votes because Player 1 has 0 blue Delegates and they also earn an additional 2 votes since they possess the Elector.

E: Player 1 earns 1 vote because they have the majority of the green Delegates (the Smear Campaign tile is wild) and because Player 2 has at least 1 Delegate. Player 1 also earns an additional 2 votes since they possess the Elector.

F: Player 2 earns 2 votes since they have the majority of the white Delegates and because Player 1 has 0. Even though Player 1 possesses the Elector, they score nothing for it as they have 0 Delegates.

G: Player 1 possesses the Editor pawn. They have so far collected 1 Smear Campaign tile, so they will have to give Player 2 one of their collected votes.

After scoring, all of the tiles (with the exception of the Smear Campaign tiles) are collected and placed back into the box and a new round begins. After four rounds the person with the most votes wins the election.

Thoughts

Firstly, I’d like to begin this section by talking about the component quality in this game. These components are phenomenal. The tokens are nice and thick, the drawstring bag is solid and sturdy, and the game board feels like it’s going to hold up very well for a very long time to come. But my favorite thing about these components is the history lesson presented in the last few pages of the rule book. That’s a very nice touch and I just think it’s awesome.

That being said, if I were to set up Revolution of 1828 on a table and then set up pretty much any other game directly next to it and ask which one you’d rather play, I can pretty much guarantee you that you’d most likely choose the other game. Nobody will ever tell you that they saw Revolution of 1828 sitting on a table and felt drawn to its table presence. Visually, it just isn’t very appealing (especially to the crowd that likes to hate on The Castles of Burgundy for its aesthetics). While the illustrations are well done and evoke the sense that you’re viewing clippings from a 200 year old newspaper, the color scheme is the typical muddled yellow, browns, and reds that have become standard fare for eurogames. While that doesn’t bother me personally, I am able to see where other people may not care for the palette.

The theme doesn’t really call out to you either. Controlling the ebb and flow of an American political campaign that occurred almost 200 years ago isn’t very compelling. That’s really strange when you think about it. In other eurogames, players are perfectly content to accept that they’re sailing ships around the Indian Ocean and trading goods at various ports in order to gain fame and wealth, but when you tell them that they’re a politician running a political campaign, some players’ eyes begin to glaze over. The game play of Revolution of 1828 feels very disconnected from the theme as well and that doesn’t help anything either. I don’t ever feel like I am running a political campaign. This is definitely a game that qualifies for the “pasted on theme” title. It’s definitely not Feld’s quirkiest theme, though. That distinction probably belongs to Spiel mit Lukas: Dribbel-Fieber (a two player game about playing street soccer) or It Happens.. (a game about anteaters trying to eat termites, seriously).

If you’re able to look beyond all of that, though, you’ll discover a very clever game hiding beneath the very drab veneer. The first time that I played Revolution of 1828 with my wife, she described it as tic-tac-toe. On deeper examination, it’s more of a strategic tug of war match. Your goal: force your opponent into taking bad stuff off of the board for themselves while leaving you in the position to capitalize on their misfortune, whether it be setting yourself up to snag the last tile (along with the Elector) and take an extra turn or force them into a corner where they have no choice but to take the Editor when they’ve amassed a pile of Smear Campaign tiles. It’s a very devious game that rewards you if you’re able to visualize several turns ahead. And like any good chess match, there will be plenty of times that you’re going to have to give up a good position in order to gain something else.

Because of the random nature of the tile draws, every round of every game of Revolution of 1828 shakes out differently than the others. Some rounds it feels like you’re just taking turns drafting Delegates while others are a frenzy of back and forth Campaign Actions as you fight for the 1 or 2 votes that are available that round. Some games the winner wins by a landslide while others they win by the narrowest of margins. But there is one chord that runs the same through each and every game: fun. I always enjoy myself whenever I play this game. While it might not be Stefan Feld’s greatest effort to date, it is a very solid one. If you’re looking for a good two player game, then Revolution of 1828 might be a good candidate.

Which Felds are you missing? Happy to help source to help you in the series if I can.

Currently I am missing Strasbourg and The Name of the Rose.