I can’t explain it, but despite being an introvert, I like social deduction games. Maybe it’s the discussion with your friends about who needs to have an unscheduled meeting with the grim reaper. Or perhaps it is numerous ways designers gamify the act of lying to your friends that can lead to incredible memories. Regardless of the reason, it has thrown me into a never-ending journey of playing social deduction games.

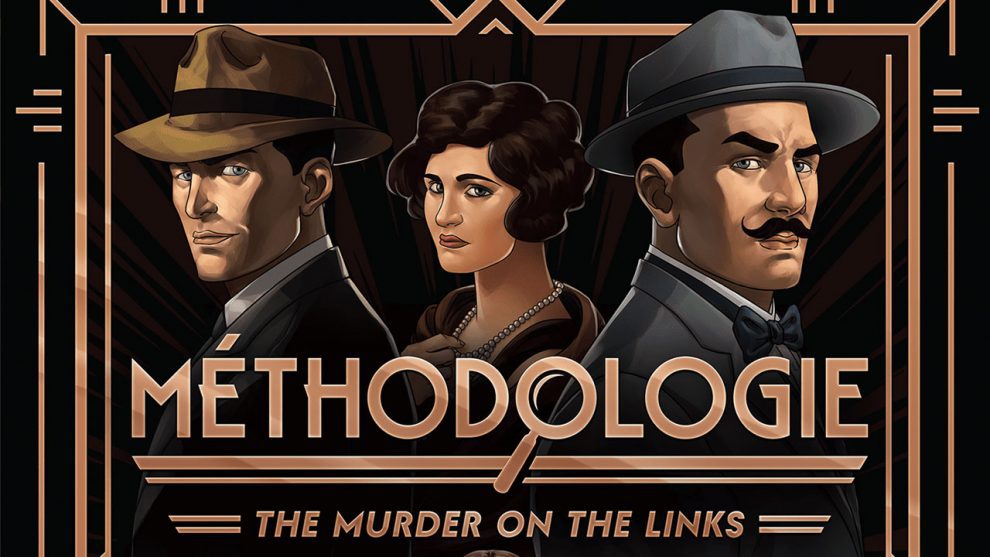

This imaginary road trip of mine has many stops, and at today’s stop, we are looking at Methodologie: The Murder on the Links. It is about solving a murder mystery, and it is based on the book of the same name by Agatha Christie.

The truth is that I haven’t followed the murder mystery genre and haven’t read any of Agatha Christie’s books. My initial attraction to this game was due to how unique it sounded after reading the rulebook. I can’t even use the old standby of “this is like Werewolf” or “this is like The Resistance” because I’m sure that statement can lead to a potential defamation lawsuit and also, no hidden traitor here. It’s a game with its own DNA.

Mission briefing

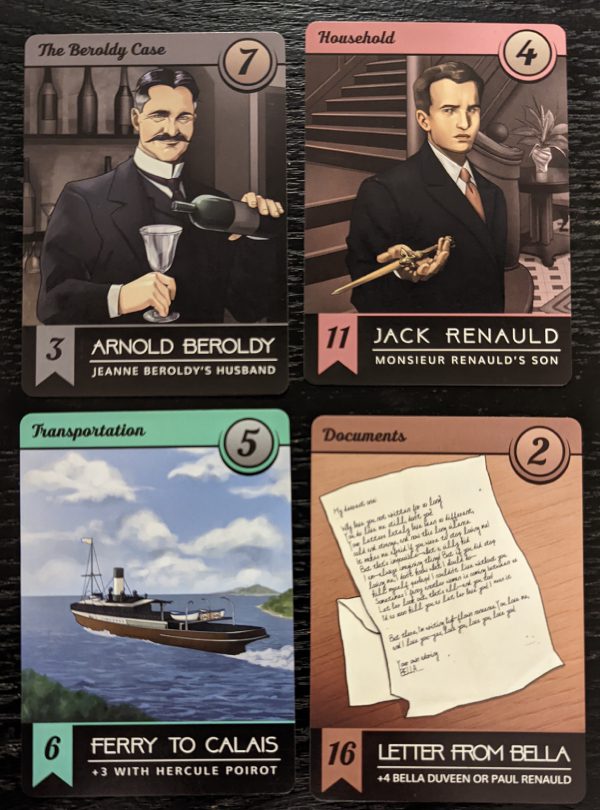

Open the box, and three boards greet you, each one representing one of the three decks: Character, Object, and Location. Each board shows an image of all 18 cards in the deck, their point value, suit, potential combos, and rank number.

The main deal here is you start with a hand of three cards of each type, meaning nine cards. During the Investigation phase, players will interrogate each other, make accusations, and finish a round by drawing from the deck. Investigations will keep happening back to back until one player has only three cards or fewer after playing their cards, forming a hand of a single character, object, and location card.

The bulk of the score is derived from these cards, but it isn’t over yet. There is an Accusation phase where players will collectively guess who has what cards in their hand. If they are correct, the accused must discard the card from their hand, which can lead to losing a noticeable number of points, especially if they combo.

That is a general summary of the game, and it’s time to take a closer look at these phases.

Examining the evidence

Going back to the Investigation phase, players will play up to three facedown cards, depending on the number of players. Playing these cards serves two purposes. The first is that they are discarded, which means neither you nor anyone else has access to them, so the elimination process begins. The second is they are used to bid to become the interrogator of that card type.

Starting with the Character, followed by Location, and ending with Object, each card type will have a single player who is an interrogator. The interrogator is determined by the person who played the lowest rank number of that card type.

Once the interrogator is determined, the suit of the interrogator’s card comes into play. Whoever has the same suit as the interrogator’s submitted card must raise their hand, and they cannot lie about this. What they can lie about is which card they have.

Upon hearing the claims, the interrogator can accuse one of the players of lying. If the interrogator is correct, the accused must discard a card from their hand—and it can be any card followed by some grumbling. If the accused does indeed hold the card in their hand, they show it, and the interrogator must discard the card from their own hand.

Does the glove fit?

This is important because while you do draw cards at the end of a round, you only draw cards to replace what you have played. Any cards discarded due to interrogations are lost, thereby limiting your options as if you just got a criminal record.

One of the things I was not expecting walking into this game was combining the challenges of hand management while keeping on a social mask. Being forced to play cards every round constantly pushes you into a compromising position since playing cards means sacrificing options. This becomes far more apparent as the decks run out. If you only have one character card in your hand and there are no other character cards to draw from, you need to burn those other cards and pray your character suit is never called out during interrogations.

I also like how the suits are not all equal. This can lead to awkward situations.

Maybe you play one of the two Neighbor cards, and you are now the interrogator. You ask who has a Neighbor card, and Julie’s hand shoots up. Now everyone knows she has the second Neighbour card and writes it down in their mental notes. She obviously can’t lie about it, so you don’t accuse her. Now she is in a tough spot with this card that everybody knows about. Does she dump it in the next round? Did she have any cards to combo with it, and if so, which ones? Will she try to sneak it into the Accusation phase? Who knows. That’s where the deduction comes in.

Another scenario is you play a Household card, and you are the interrogator. Three hands rocket above the table, and because they are jerks, they all claim to have the same card. One of them is clearly lying, or it could be all of them. Furthermore, you only know if they have a Household card in their hand, but not how many. Maybe that hand doesn’t represent one Household card but three.

Of course, one will easily ask, “why not tell the truth?” and the game bites you in the rear and responds with “Accusation Phase.”

J’Accuse

The Investigation phase ends when, after playing the cards, a player has three or fewer cards remaining in their hand. The cards played are discarded but are not publicly shown to anyone else, serving as information asymmetry for the players.

Starting with the Character board, players will openly discuss, and vote on, who has what card in their hand. There are no turns or any sort of order. This is a free for all discussion, with players both collaborating with you as well as conspiring against you. It’s a contest of emotions where you have to keep a poker face when you see the voting token hovering near your card or being careful with your words. For such a simple system, it’s a genuinely engaging experience that tests out your deduction and social skills without convoluted rules.

Yet it’s also here that my feelings about the game began to wane. The game isn’t subtle in the purpose of the two phases. The Investigation phase is to eliminate cards and use accusations to stifle the options of the other players to create high-scoring combos. The Accusation phase punishes players who are too passive or too honest, allowing everyone to peck at each other’s hands like proactive vultures.

While the concept sounds good and keeps things in order, my main issues reside in the information asymmetry and creating card combos.

Cross-examination

Simply put, the card combos are too linear. Most of the locations and objects only give bonuses to a particular character. Grab the Masked Men, and you want to find the Shovel. Go for Paul Renauld, and the man wants his Fairway Bunker and Golf Clubs. I understand this is in service to being faithful to the source material, but from a game design perspective, it’s rather limiting.

The bigger issue is information asymmetry. As I stated, you dump cards from your hand at the end of the Investigation phase and no one sees them. This allows you to throw cards away that people have concrete information on. You’ll likely end up with a handful of cards that barely combo together, yet will probably not leave your hand since the other players need to go through some lucky hunches. This can lead the Accusation phase into a strange situation where people are taking random guesses that can feel as difficult as sniping the president with an elephant gun.

I will state that this is coming from the perspective of somebody who spent an unhealthy amount of hours in the social deduction genre. Any social deduction game that I review will inevitably be compared to other social games such as Blood on the Clocktower, Captain’s Gambit, and Human Punishment. In other words, I have options, and an experienced group to handle them.

On the bright side…

I will also admit that most social deduction games with a hidden traitor element are freakin’ weird. They are not family-friendly. They are family-hostile.

Methodologie’s biggest strength is it’s a unique game that is palatable to the family audience. There are no odd rules to memorize, special powers with strange interactions, or any nonsense to overcome. It’s a clean ruleset that anyone can understand with a visual narrative that has widespread appeal.

Even though I find a number of issues with the game design at a higher level, the family audience will not scrutinize the rules so much. If families cared about game design, Exploding Kittens and UNO would’ve been escorted out of the market ages ago. I can easily see this game being pulled out on occasions that offers an experience that no other game can provide. You can’t exactly pin the tail on the genre donkey with this one because of its unusual style. If you have high standards of social deduction as I do, Methodologie will likely annoy you. For families looking for a unique experience that isn’t a copycat of other bluffing games, you might find something special here.

Add Comment