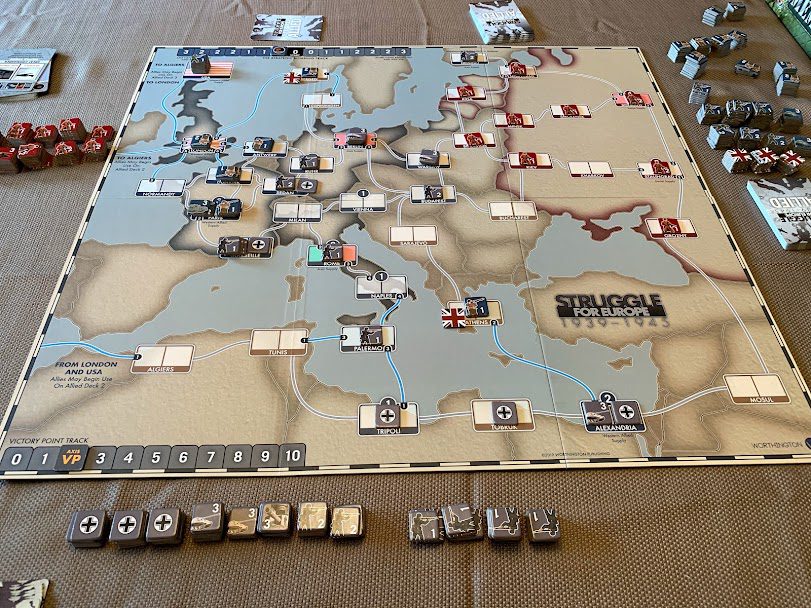

It’s pretty difficult to get a wargame on the table that manages to cover an entire continent of the largest conflict in history and deliver a satisfying resolution in under two hours. When dealing with the strategic level in wargames, production, economics, and logistics are just as important as actually fighting battles. Managing to include these aspects of modern war can lead to bloat, or a granularity that makes finding the time to play difficult. I was intrigued, then, when I heard of Struggle for Europe, 1939-1945 from Worthington Games.

A mechanical sequel to 2018’s Lincoln, Struggle For Europe takes a simple mechanical idea, the use of a changing deck of action cards, unique to each side, and applies it to an area control wargame. The promise of a concise grand strategic game of WWII’s European theatre for two players using such innovative mechanics seemed too good to be true. I had to check it out. I’m glad I did, because I think I’ve found one of my new favorite wargames. And I like a lot of wargames.

How to Conquer Europe in Two Hours

Players take control of either Axis or Allied Powers. The Axis player controls a monolith, with Nazi Germany and her allies represented by a singular command structure and set of units. The Allied player divides their forces into three, with The British Empire and European allies, The Soviet Union, and The United States all given separate counters, and in the case of the east-west divide, given different movement restrictions. (No Soviets in Egypt, for example).

Both sides are hunting for victory points which are earned either by capturing important cities held by the other side, or else through strategic bombing. There are a few other victory conditions, but we’ll cover that when we get to the cards.

To capture key cities and achieve victory, players build armies of different sizes (1-3), maneuver them around Europe, and fight battles. The map is point to point, with significant areas connected by either land routes or sea routes. Each area is split into two and, in a fascinating bit of innovation, spaces can be either wholly occupied by one side, or contested. Usually when battle occurs as an army moves into a space occupied by an enemy, the fate of that area is decided. But, if the defending force opts to retreat, the area is divided and becomes contested. Both sides can continue to move forces into contested spaces, making for some interesting stalemates and set piece battles. But how does any of this happen?

Not a Deck Builder, but a Deck Destroyer

The game is entirely driven by the play of cards, with two actions allowed per player turn. Each card will have a number of uses, from a bonus to combat, a special event, a movement type, and unit building possibilities, though only one is ever chosen. The Allies and Axis have their own decks, but the really interesting twist is that there are two extra decks waiting on the sidelines for each faction. When a deck is exhausted, the discard pile is shuffled along with the next deck in order, giving both sides a changing selection of cards to work with.

For the Axis, their three-deck progression attempts to represent the strong start and gradual decline under the strain of total war that affected Axis economies. They start capable of major attacks, have the opportunity to build large army counters, and have the initiative when it comes to strategic bombing. As they work into the second, and finally the third deck, their available forces become weaker, their ability to build armies is replaced by defense-oriented fortifications, and their airpower diminishes. The Allies, on the other hand, start relatively weak, but grow in strength with each successive deck. In the Allied case, each new deck introduces another faction, first the Soviets and then the United States. This not only keeps the game flowing along mostly historical lines, it also offers interesting choices. For example, the Axis player is free to attack the Soviet Union whenever they like, but doing so will immediately cause the second deck to be shuffled into the Allied player’s current deck, unlocking the Soviet forces. But they could leave it until the Soviet Union joins of its own accord when the first Allied deck runs dry.

So, what about card destruction? Both sides have cards that can create new armies. Armies come in one, two, and three strength points. Building two and three strength point armies comes at the cost of permanently removing that card from the game. This, of course, removes the other elements from that card from being used, but also shrinks the deck the next time it is shuffled. This is especially relevant for the Allied player, who will lose the game if they don’t reach their objectives by the time they finish their third deck. Choosing when to permanently remove cards becomes a critical part of the strategic decision making for both sides.

War is a Brutal Affair

When it comes to actually fighting over and capturing ground, the strategic and tactical dilemma that faces both sides becomes apparent. With only two actions per turn, there is never enough time to do everything that you want to do, with big offensives taking several turns to build up. The game then becomes a fascinating tug of war, with concentrations of troops jockeying for key positions while flanking operations try to poke holes in the enemy’s lines.

Battles themselves are bloody. To initiate an attack, a player must play a card for its movement (or not if the area is contested) then play a card for its combat bonus. This card is placed face down, and the defender can play their own bonus card face down to counter it. Then the total combat strength of each side is added, the defender receives any bonuses from terrain or fortifications, and the higher total is the winner, with ties going to the defender. The loser must lose half of their units (not combat strength, whole units) rounded up and retreat. The winner loses half rounded down, but no more than the loser. This makes combat very costly, so attacks can’t be flippant.

Abstract, Yes, Authentic, Also Yes

This is a fairly abstract game about war and I understand that many are hesitant to get into something that might abstract away a lot of the chrome that players tend to look for in a game like this. Thankfully, I believe the way Struggle for Europe handles its mechanics presents a thoroughly authentic, if not accurate, feeling experience of World War Two in Europe. There will be an initial rush of Nazi victories as they bring their superior strength to bear in France and North Africa. The Western Allies will desperately hold on, playing cards to counter strategic bombing where possible and holding onto key points like Egypt and the British Isles. The introduction of the Soviets can turn the tide, but a prepared Germany can push deep into Russia. If the United States enter, the game becomes a desperate bid by the Axis player to hold onto their gains and run out the clock.

The cards themselves add some flavor, like special events including airdrops or wolfpacks in the Atlantic, but it is the flow of the decks, each of which adds new critical decisions and sets the tempo for the next few turns that really shine.

A Struggle Worth Experiencing

After some time with Struggle for Europe the charm of the mechanics and their ability to tell an engaging narrative of the Second World War really stood out from the crowd. In one game Paris held, just barely, and the Axis forces instead pivoted to the rest of Europe. A stalemate of massive forces endured along a similar axis as the First World War in the west, while a desperate battle of maneuver erupted in the east. Another time an overzealous Allied attempt to strike at Germany through Yugoslavia failed when counterattacking forces in North Africa seized Egypt. Each time was entertaining, and crucially, over in under two hours.

There may be a threat of diminishing returns, when dozens of plays lead to ideal first moves or consistently better strategic choices, but I don’t foresee that happening until long after the game has satisfied its purchase price. Personally, Struggle for Europe has become one of my wife and my go-to wargames when we don’t have the time for an all day affair. I really cannot wait to see how Worthington and designers Grant and Mike Wylie build upon the successful formula seen here. The First World War could very easily receive a similar treatment, as could the War in Asia, with some modification. In any case, I can’t wait to see what I’ll be struggling over next.

Add Comment