When I first read the rules to Kevin Luhn’s Fish ’n’ Flip, which I did under duress at a table populated by expectant children, it seemed straightforward. Work together to shift fish into groups so they can escape the trawler’s net, a maritime Candy Crush. You pick a card and play it for its effect: swap two fish, flip a fish, flip a row of fish, flip a column, etc. Each species of fish—eight in the box, with a random four used in a standard game—has a unique ability that activates when flipped.

The game that followed was one of the most difficult, brain-burning puzzles I’ve experienced in recent memory. Discrete fish abilities snowballed into dizzying sequences of possibilities and permutations. Getting three fish of the same species together, while having them face in the same direction, seemed nearly impossible.

By the end of a subsequent game with adults, I was exhausted.

“This should be an app,” one of them said.

“This is for children?,” another asked.

Without question, this was one of the most intense puzzle games I’d ever played. We were all flummoxed by the fact that this game was clearly being marketed to children. There was just one problem: I had nearly every rule wrong.

In the real world, Fish ’n’ Flip is a relaxed, pleasant puzzler. The differences from Fish ’n’ Flip (Andrew’s Version) are simple, but their impact is profound. Groups need only consist of two (2) fish, not three (3). That lowers the grade of difficulty, and makes the game significantly less susceptible to the luck of the draw.

The more important difference: Specific fish powers are assigned to each player, and only activate on that player’s turn. This has a dramatic effect on the difficulty of execution. Turns take a matter of seconds as opposed to minutes. Synapses no longer sizzle. Cortexes can cruise along. With the proper rules, Fish ’n’ Flip is entirely accessible to the young players its art and age limit are clearly catering to. Makes sense. Use something the way it’s designed, it’ll probably work better.

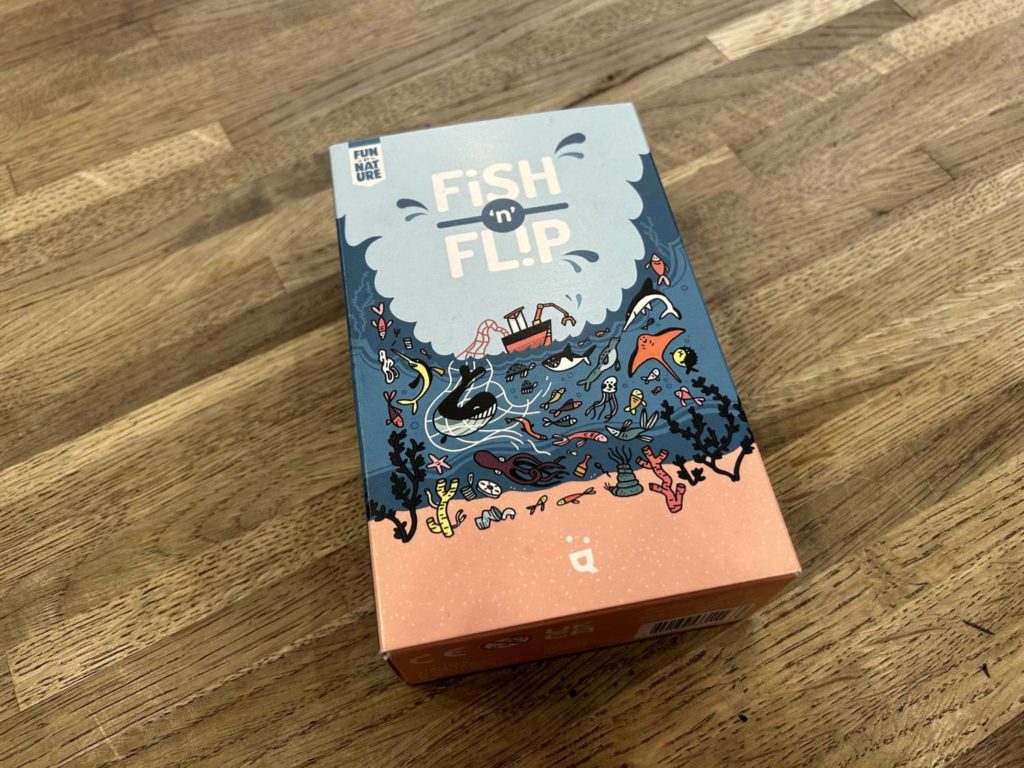

I love the biodegradable packaging. A fresh-from-the-store copy of Fish ’n’ Flip could be buried in a hole in the backyard to decompose, and it would do so gladly. Artist Dominik Wendland’s illustration on the cover, reminiscent of the underwater fantasia that opens Ponyo, is utterly charming. The art on the cards doesn’t live up to it, though I think that may have more to do with publisher Helvetiq’s formatting choices than the art itself. I was inclined to blame the illustrations until I saw the cards from the original Gaiagames production, which feature different backgrounds and no white border. Those look much better.

The rulebook is not why I had so many rules wrong, but it could be a little clearer about some things. I also wish Helvetiq had included the campaign mode, currently only available through their website, which I enjoyed. I wish that had been included in the rule book. It’s mentioned in passing in one sentence, and many people will miss it. It is worth noting that the campaign mode democratizes the fish powers, and comes much closer to the original Andrew’s Version experience. That makes it much harder.

It’s hard to know the extent to which my experience of Fish ’n’ Flip has been influenced by my original, erroneous remix. It was absurd, but it was also audacious in a way that I was forced to respect. Fish ’n’ Flip as it truly exists is pleasant, familiar, and fine. If you’re a family with children around 8-10, looking for a cooperative game where everyone can participate equally, you might even flip for it.

I loved the unique idea and the fun ways you could try to test the rules of the world around you. Goal of the game. Various animals have been caught in fishing nets: players will have to work together and program their actions in order to free them.