I can think of no greater thrill in gaming than hearing some favorite is on the move. Be it a favorite game, designer, or artist, nothing stirs quite like finding out some beloved something or someone is begetting another experience for my enjoyment.

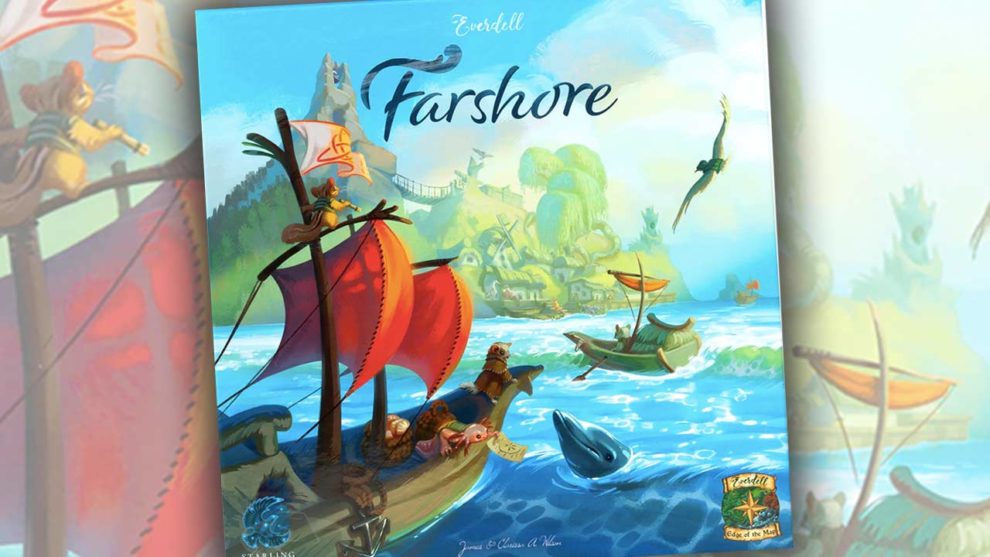

We received word here at Meeple Mountain back in May that a new project was coming in the world of Everdell, the first standalone outside the heavily expanded original. Needless to say I was ready. Or at least I believed I was ready. With nearly a month to think about it before the little bundle arrived, my mind set to racing. If given the chance, what would I do next with my favorite gaming world?

I’m now several plays into Everdell Farshore, and I have thoughts. Some of them are exactly what you might expect if you’ve read my affectionate ranking of the expanded Everdell world or my strategic thoughts on Everdell. Any public mention of the Meadow seems to produce some sort of reflexive doting in me that I just can’t contain. Keeping that in mind, though, you might be surprised at a couple considerations in this particular review.

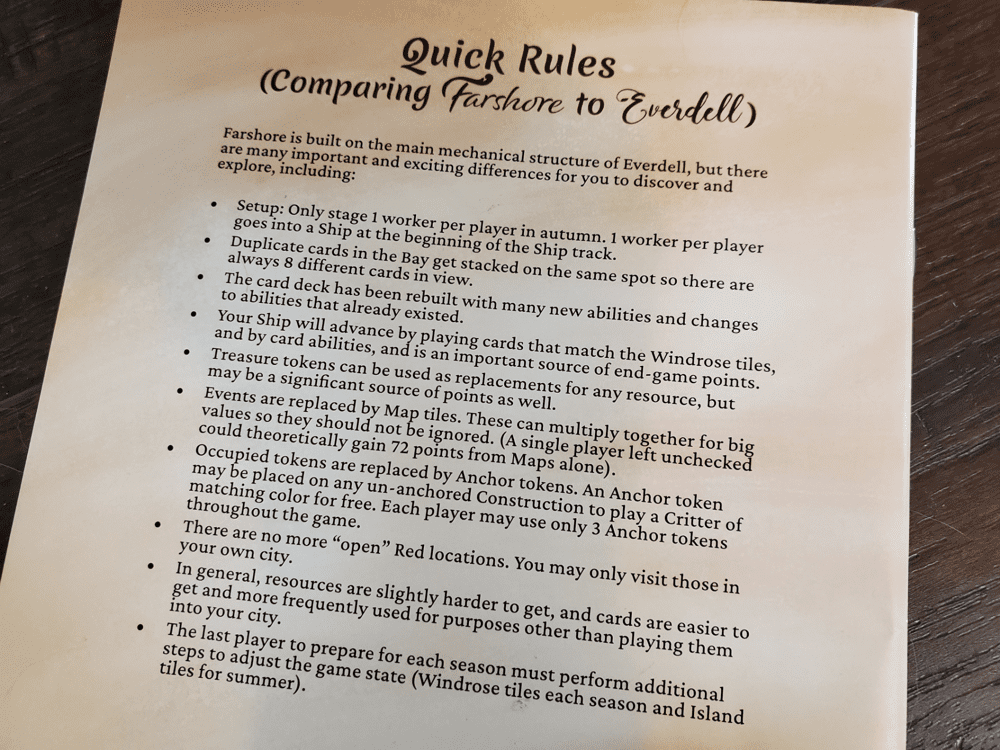

For the familiar, Farshore is a slightly modified reimplementation of Everdell on a seaside map with a handful of new mechanical considerations. How similar? The back of the rulebook is a list of the few changes from the original. For the new initiates, Farshore is a charming seaside world in which players send out animal workers to collect resources to build a burgeoning city of Constructions and Critters, move their boat along the sea to collect treasures, and deliver maps of their progress all while keeping a watchful eye on the winds.

Down by the shore

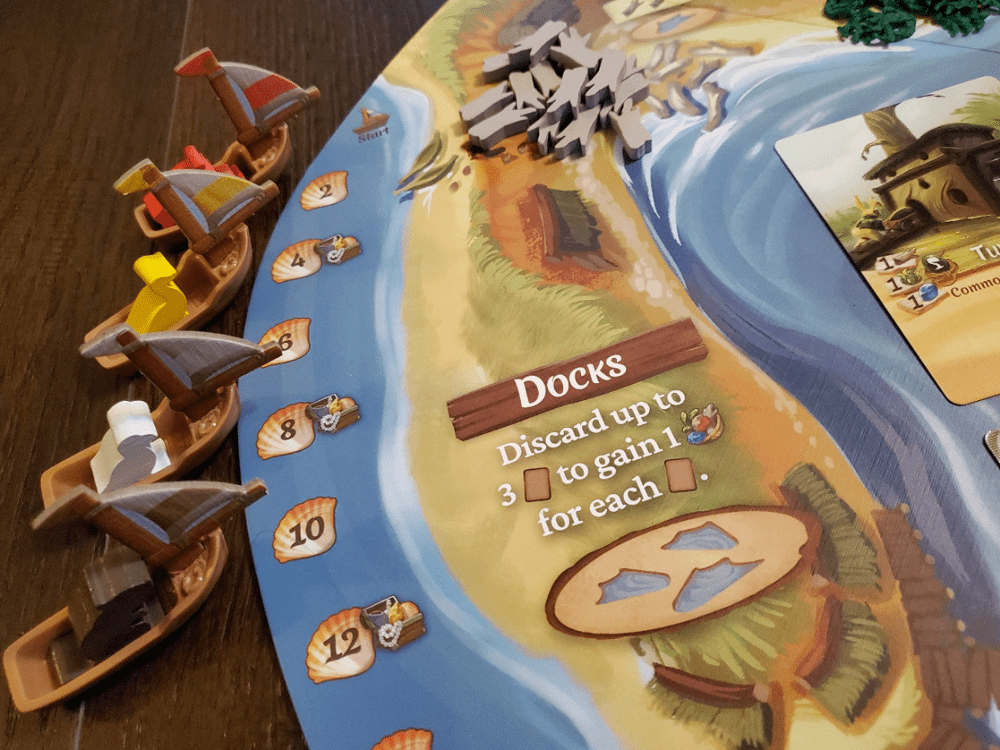

The Farshore board features a shoreline from which players collect the four primary resources: wooden driftwood, delightfully rubbery seaweed bits, blue sea glass, and whimsical mushrooms. There is no doubt Starling knows how to bring a world to life. Two spaces extend out into the water to form the Bay. The Docks are for trading cards for resources. The Lookout is for shedding cards to draw up to the maximum hand of eight.

The Bay itself is the home of an ever-rotating market of eight cards. Out from the bay, up to four Island locations provide a bit more heft in collecting resources. There are ten Island overlays to lend variety. Around the outside of the Bay is a track along which player boats will travel—boats peopled by an animal meeple, of course. Players choose from crabs, beavers, ducks, and puffins.

The Dunes contain six stacks of maps that serve as achievement markers as certain quantities of cards are played into each player’s city. Visiting the Dunes involves collecting a map that will take part in a calculated bonus at the end of the game. Next door, two stacks of Windrose tiles will indicate a rotating set of targets for individual card plays throughout the game.

Each player begins with a hand of cards and three metal anchors. These anchors, when played upon Construction cards, will allow for the free play of a Critter, but they are limited. A turn consists of one of three possible actions: Send a worker out to collect resources, Play one card from the Bay or the hand into their city (paying its cost), or Prepare for season—an act of rest, refreshment, and maintenance. In Everdell, players move asynchronously through four seasons, preparing only as their own personal situation dictates.

Shoreline locations are limited to one worker each, as are the Islands. The Docks, Dunes, and Lookout are infinitely open. Between the Lookout’s gift of a full hand and the Docks’ gift of resources for cards, it’s not too difficult to collect if spaces are occupied.

Cards come in five varieties, each signified by an icon and a color and performing a distinct type of function. The goal is to use a combination of one-off action cards, evergreen production cards, worker-placement cards and rule-enhancing engine-building cards to lay a city of 15 cards into a personal tableau before the end of the final season. Endgame bonus cards also dot the horizon and are considerable both in the scoring capacity and cost.

When playing a card, players check the Windrose tiles to see if they matched the conditions: maybe Critter and Green (Production) or Unique and Tan (Traveler). Each match grants a single move of the boat along the outside track. This track has a potential for 60 enormous points, so catering card play to the tiles is a key consideration. Some cards also grant this movement. Periodically along the track, players recover a treasure that serves as a wild resource or a 2VP token at the game’s end.

As a player acquires a set number of each suit of cards, they can claim maps from stacks with diminishing values. At the end of the game, players add up the point value of all the tiles and then multiply by the number of tiles to determine their final worth.

When a player has no cards to play and no workers to send, they Prepare for season. Each season grants a boon of resources, cards, or sometimes both. The last player to Prepare each season changes out the Windrose tiles to institute a new target pair. The final player to finish the Summer season also sinks two Islands, making resource collection more competitive in the home stretch. At the conclusion of the fourth and final season, the game ends. Points derive from city cards, gathered treasures, the boat track, accumulated shell point tokens, and accumulated maps. The highest score wins.

My initial reaction

It had been my hope for the last few years that, at some point, James and Clarissa Wilson and the team at Starling would spread their wings and develop other games in the Everdell world. They’ve built such a comprehensive sense of place and a compelling cast of critter-characters that I want to see what happens in their day-to-day lives.

There are two ways to go about such a thing. One is to build a new game in the old world, the other is to build a new world around the old game. If I’m being honest, I wanted the former with every fiber of my being. When the latter arrived, I was disappointed. It is obvious from a single look that Starling has taken the Ticket to Ride approach with this first in a coming series titled Edges of the Map.

For those who may be unfamiliar with the wide-spanning train series, Ticket to Ride, every game is born of the same spirit with the same base mechanics but implemented on a new map with a few tweaks to the system. It works. It works well, in fact…with trains. But does it work with a character-laden, unique card-heavy, worker placement system like Everdell?

I cracked open the shrink and fell in love with the aesthetics as I knew I would. The map is exquisitely round and inviting. The resources are absolutely phenomenal from top to bottom. None replaces the squishy berry on my list of favorite components, but the seaweed is amazing and the mushrooms are s’darn cute. This Everdell style is unassailable and overwhelmingly cozy. Like the Evertree before it, the Lighthouse will go down in my book as entirely superfluous and, if it be possible, even less useful as a 3D structure. We didn’t even use it in the first game. But it’s there, I guess. It might serve best laid down flat rather than assembled.

The cards are astounding. Gone is Andrew Bosley from the artistic mix. Jacqui Davis came on board to illustrate My Lil’ Everdell, the lighter family version of the base experience. She kept pace here, reaching out for the bar that had been set so high. These characters are great. There is some crossover with the originals by name, but the illustrations abound with bonny charm. Being a seaside setting, I think the avian art here even gives Wingspan a whimsical run for its money!

I found myself internally conflicted, though. I was hoping for a drafting game that walked through a trying season on the farm with the Wilson family mice, a pick-up-and-deliver experience about the efforts of the Miner Moles, a tile-laying area control title about the Pirates, or heck, a rail-laying game about the Newleaf train station. Is it odd to say I was lukewarm about playing my favorite game when it wasn’t quite my favorite game?

I think my instant hesitation came not only from the game in hand, but from the fact that this is the first in a series: Edge of the Map. There will be others. Everdell is going to be tinkered with for the foreseeable future, and I just. Wasn’t. Sure. I’m still not sure.

Minding the tide

But many of those thoughts are borne of certain expectations. To be honest, none of them really matter when it comes to reviewing Farshore. How is the game? It’s lovely. It’s lovely because Everdell is lovely.

The worker placement is tight because the lucrative spaces only take one meeple at a time, but simultaneously quite free because a full hand of cards is ever-present, and three resources of choice by discard. The disappearing Islands also create a nice tension in the late game just as players trigger their green sites one last time and look at a more trim set of options. Plus, you have the pervasive pressure over whether to keep or spend the treasures. Overall it’s an interesting economy.

The narrative tension, so to speak, comes from the desire to obey the Windrose tiles. When a card in hand or in the Bay matches the tiles, the little voice in my head says I must engage. But are these voices to be obeyed? The track moves by twos until 40pts and then switches to ones, which means early movement is important—the ROI is significant. But as the game wears on, those singles are often less valuable by comparison and the mental struggle is deciding when to obey the tiles and when to focus on a larger payout elsewhere.

That elsewhere is often the Dunes. The map tiles can be a nice source of points, but they have to be a game-long strategy because there just won’t be enough time at the end to grab them all. If a player grabs a couple twos and a few ones, that could be 35pts by the end—no slouch indeed! But having a pair of ones is 4pts at the end. Either you’re in or you’re out, and it’s a decision that must be made earlier rather than later. If you’ve not chosen to enter that game, it’s entirely possible you’ll find yourself with a full city and a spare worker or two left twiddling their thumbs at the end and those 4pts are all that’s left. Whimpers like this happened on more than one occasion.

Without a doubt, the purple Prosperity cards take on a significant role in Farshore. In fact, I’d be so bold as to say they are the most essential chase. Having a card that grants a point per treasure, a point per treasure space passed on the boat track, two points per unique critter, two points per that—it all adds up so fast. Plus they all hold a printed value of more than double most of the cards in the game. They simply must be sought and secured. But they are expensive.

The cost of Prosperity makes the anchors so important. Saving at least one to pull in a free purple critter is essential. Saving two is even better. Why use an anchor for a 2-mushroom Traveler critter when you could add 15+ points to your score with a purple fella of some sort? The anchors are a nice way to cheaply bolster the city’s early production, but there is clearly a best way to spend them.

And that brings me to my chief issue with the game itself. I believe Farshore is a game that can be largely figured out. After a handful of plays at the various player counts, there seems to be a best way to play, a best thought progression that leads to the best score. Now that might be more than partially mitigated by a group of people at the table who all know the system well and who wrestle one another within the system, but I believe they’ll all be chasing the same ideas to different degrees of effectiveness. For this reason, the casual first-timer probably has no chance against someone who has played the game a few times before. There are tidal movements, rhythms that become apparent, and I worry that Farshore won’t withstand repeated plays—at least not like the original.

Docking the boat

All that being said, Farshore is a solid game. It’s not a game without foibles, but it’s solid. I struggle at this point to imagine what it would be like to play as someone who has never seen Everdell, but I think this would be a delight. Inside out the visuals are stunning. The unique physical bits are engaging and satisfying. The rulebook is crystal clear—the kinks have been ironed out over the last five years—which eases the entry. The card text is also clear as a bell. Some of the similar card functions from the original are even more clearly explained here. The board is printed with icons as reminders for the procedures at the change of season. And the gameplay is fun. I have no hesitation recommending sitting down with Farshore.

If given the choice right now, I would still play the original. Years later I still believe there are things I’ve not discovered, synergies I’ve not unearthed in the Meadow. Farshore is like a summer vacation for the Everdell fan: it’s nice to get away, and in one sense you’re entirely pleased when you’re there, but at the end of the week you’re ready to go home.

I had the opportunity to play an early copy with a group of friends, and I think that your review captures the feeling of the new game nicely. It’s definitely everdell, but there are parts of it that drove me to near insanity while we played. It’s just not as good as the original or it’s expansions, and I don’t see myself playing this over those when give the opportunity.

Outside of the gameplay and mechanics, the kelp and boat components just need to be changed. I could never pick up the amount of kelp pieces that I intended to because they all tangled together, and certainly someone in this world can figure out how to do those boats in a way that is more of a race around the island. Even a simple 90° turn of the mast so that it points to your score would be a massive improvement.

Thank you for reading and commenting! I am glad you were able to sit down with a copy. It’s a treat to see games before they hit the market. I also totally understand your frustrations with the components. They are distinct, and I love that, but they are not without flaw.

We’re entering new territory with this title, so it will be an interesting ride moving forward!