Disclaimer: The views presented in this article are those of the author only and are not intended to represent those of the broader Meeple Mountain family!

A game like Ierusalem: Anno Domini is bound to raise eyebrows for any number of reasons. It raised mine for three, which I share because I feel it might help establish perspective. First, I was curious because of the game’s subject matter—factions attempting to get near to Jesus during that final Passover meal before His crucifixion. Any attempt to even hang around the historical fringes of a religious themed game begins on tenuous ground at best.

Second, I raised a brow because this subject matter is of supreme importance to me personally. While a game that dabbles in religion immediately creates a certain broad tension, that palpable je ne sais quoi is amplified for each individual based on their personal experience, faith, and understanding. Any game that explores any facet of my faith falls under the scrutiny of head, heart, and soul as it would in the hands of any other.

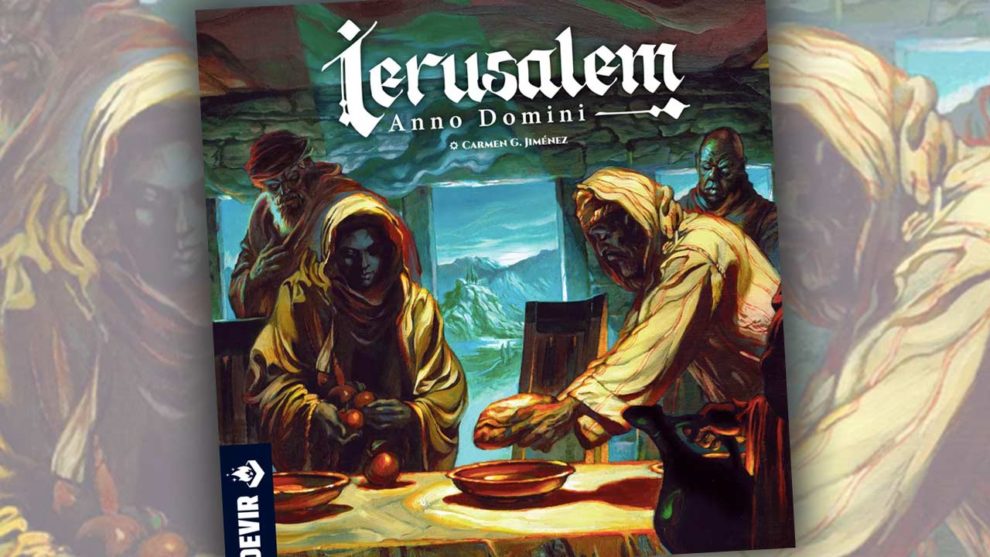

Third, I was impressed to see publisher Devir lend their pedigree to what is bound to be a divisive title. I’d imagine there are folks who are rooting for success and failure from every background and worldview for wide and varied reasons. I embraced this exploration partly on the quality of Devir’s past titles. This is the first design from Carmen García Jiménez, though, which seasons the whole pot with a taste of the unknown.

The truth is, there are a lot of bad games out there that tinker with religion. Most often, such games adhere to doctrine—honorably so—at the expense of design. Few with a vested interest in any faith would tilt the balance in the other direction. But a religion like Christianity, with anchor points both inside and outside human history, leaves open the possibility of an exploration that is faithful in spirit, curious about the historical narrative, and respectful of doctrinal implications, provided the development team is expertly trained in spinning numerous priceless plates.

The historical significance of Jesus of Nazareth cannot be overstated. It is a subject for conversation whether His moment can or should be presented as an article of play. To be honest, such an essay is beyond the scope of a board game review. For now, Ierusalem: Anno Domini is out there in the wild. My task is to engage and report, and I wanted to share just a slice of my viewpoint at the outset because I know folks care about the angle on topics like this.

I must admit: when I saw the beautiful box—folks have complimented it before even reading the title—and felt the sheer weight of its contents, I allowed myself to have high hopes. The proof is in the play, though. Has Devir pulled off a success? I’ll say it’s encouraging.

Overview

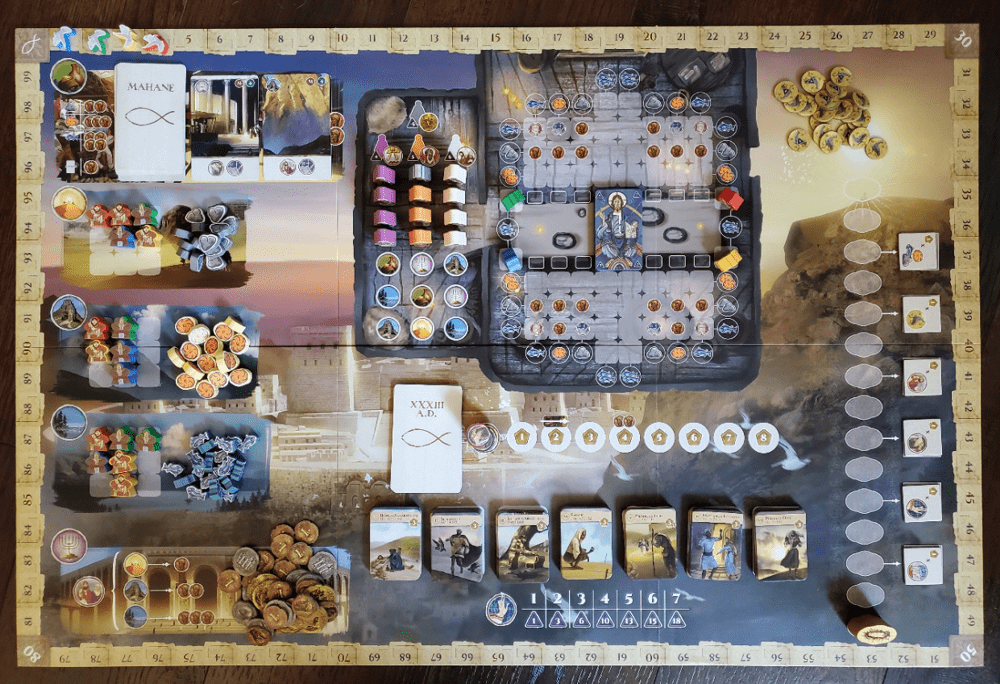

At its center, Ierusalem: Anno Domini is an area management game that takes place on a number of concentric rings around the table at the Last Supper. Each player controls a faction that is posturing to get as close to the table as possible, seating the apostles and claiming seats behind. To fill the seats, factions send followers out to collect stone, bread, and fish to bring to the Supper according to the coordinate grid around the table. All of this happens through a mechanism that I’ll call “deck building with short-term memory loss.” Along the way, followers gain by hearing parables and sharing favors with others. The game’s timer is controlled by the activity of the Sanhedrin, the Jewish ruling council, as they eventually approach to arrest Jesus on his way to the cross.

What makes Ierusalem: Anno Domini interesting as a package is that there are three related but unique experiences in the box depending on the player count. I’ll begin with the core mechanisms and then offer some detail about the various player counts. If you’re looking for less detail, feel free to skip down to the thoughts on components, gameplay, and biblical fidelity.

On the mechanisms

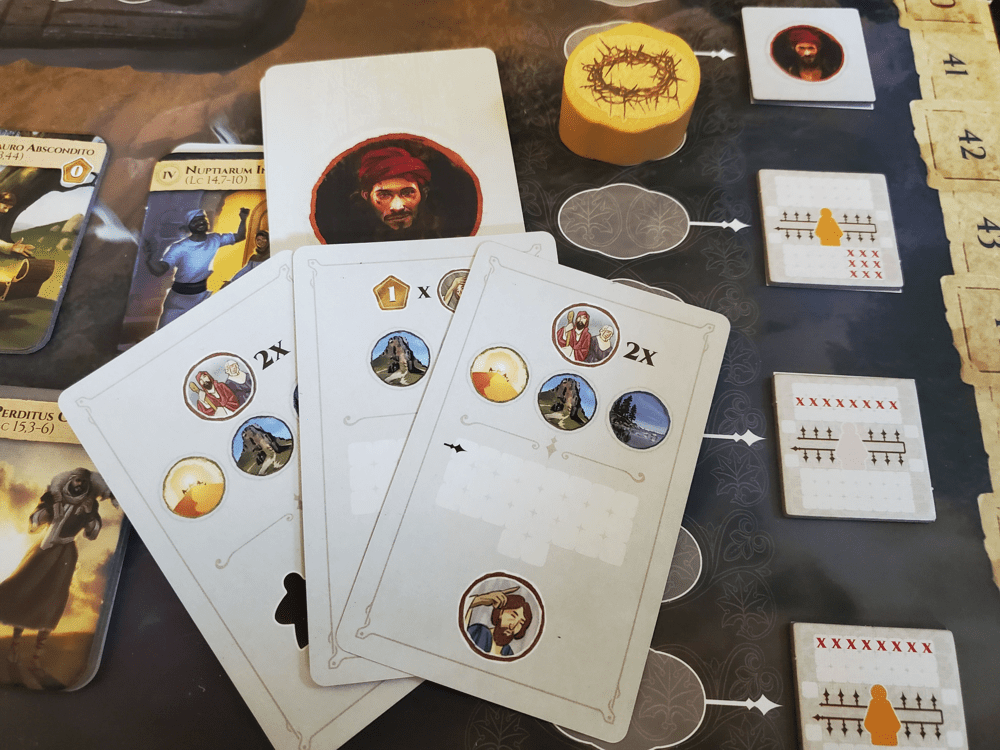

Deck building with short-term memory loss? Every player begins with a deck of ten cards from which they maintain a hand of five. Throughout the game, special cards are available to enhance the deck, but once they have been played—and potentially turned in for points—they are returned to their original decks, never to be seen again.

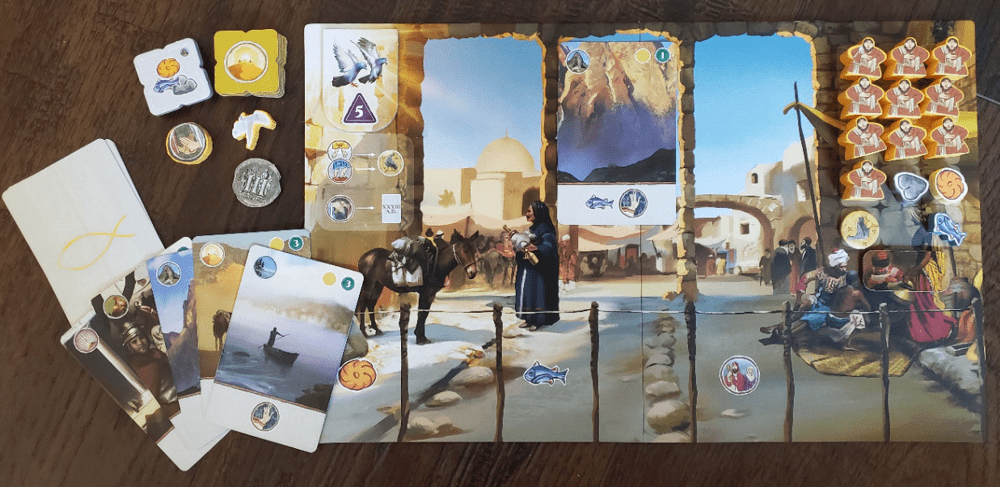

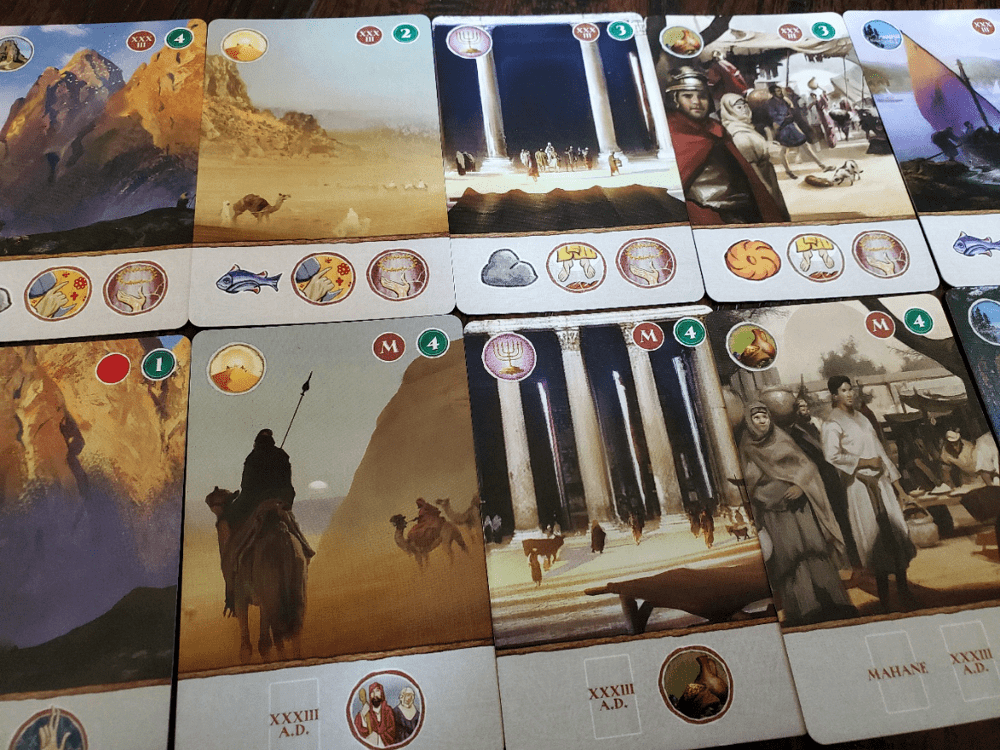

A turn begins by playing a card into one of three available slots on the player board, after which the icons are resolved top-to-bottom and left-to-right. The top icon will trigger the action from one of the game’s five locations. Desert, Mountain, and Sea locations grant stone, bread, and fish respectively, one for each follower (meeple) the player has in that location. The Temple is for sending followers out into the resource-bearing locations by paying coins. The Mahane (Marketplace) is for the selling of goods and the purchase of special Mahane cards.

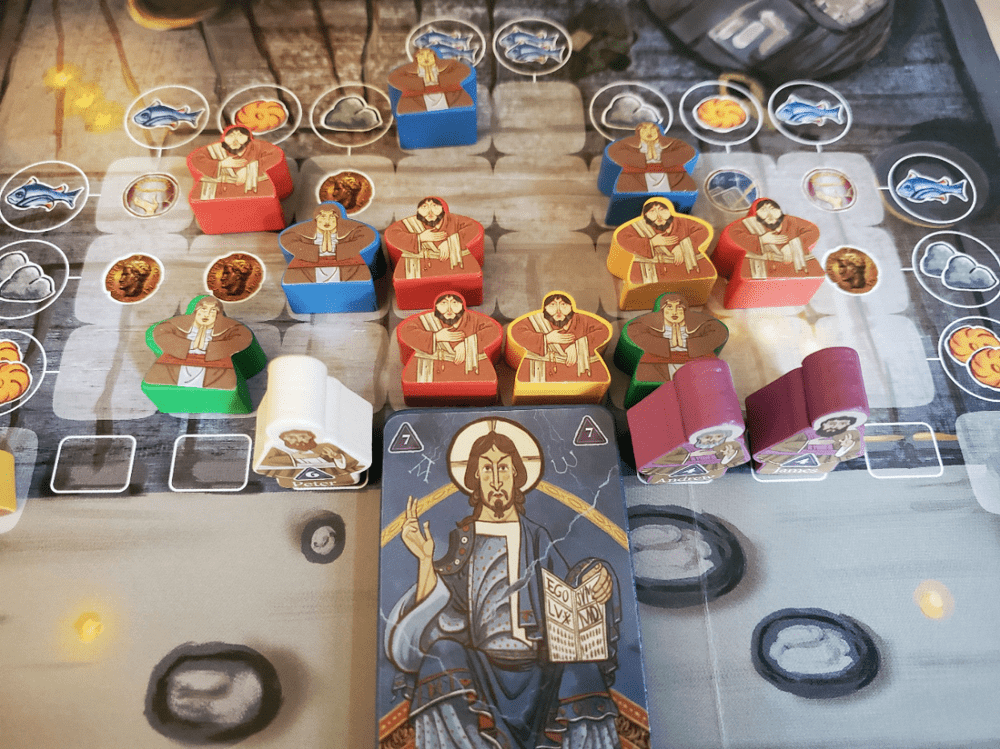

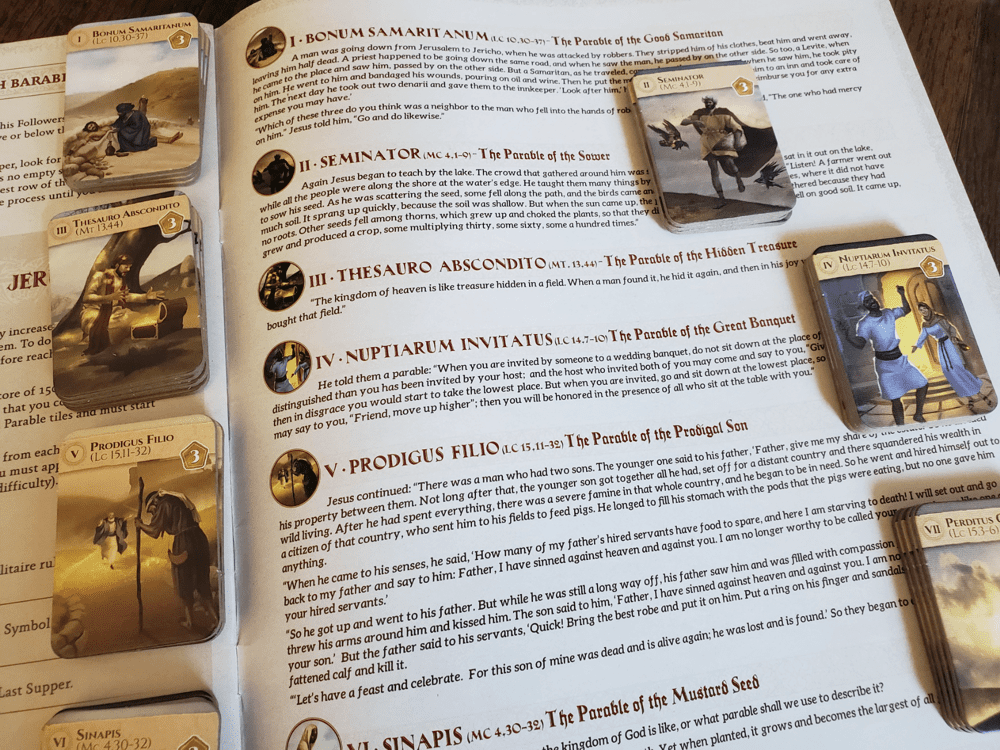

While we’re talking about the top of the cards, these icons are also eventually used to visit the apostles and place them at their seats for the Supper. Each setup utilizes three combinations of these top icons to be collected and arranged in the slots on the player board. If a player gathers the icons in the correct order, they visit an apostle after their card play. The visit means assigning them a seat, which will later determine the point value of the followers behind each of the apostles. If an apostle is a six, then the first seat behind will score six at the end of the game, with the next row scoring five, then four. The race toward and the tension around these placements are a significant portion of the game’s strategy.

Once an apostle has been placed, the player discards the set in exchange for points on the scoring track. Special cards return to their decks, and player cards return to the player’s discard pile. In addition, a one-time favor is extended to the player. This might involve sending a follower to the Supper without cost, triggering an interim scoring, or exchanging follower seats with another player. The player who places Judas receives five coins, but every seat behind him results in a loss of five, four, or three.

The bottom of the card will contain anywhere from one to three icons, depending on the deck it came from. These icons activate the remainder of the possible actions. Listening to Parables involves collecting up to seven tiles in order, each depicting a biblical parable (the text of which is available in the back of the rulebook). The tiles score instantly with diminishing values—getting there first is preferable—and at the end of the game based on the total number collected.

Doing a Favor means gifting one of eight special tiles from a player’s personal stash. One side of the tile will grant an immediate boon—resources, coins, etc. The backside will serve as a location icon in a later attempt to visit an apostle, one that overrides the whole “keep things in order” mandate. For each Favor given, players move up a score track and gain supremely lucrative XXXIII A.D. cards, which always contain three bottom icons.

Calling a follower mirrors the Temple action, but without the cost of coins. Changing places involves switching seats with another player’s follower at the Supper. Resource icons grant a single stone, bread, or fish. The Denarii icon issues a coin. The Redistribute icon allows for the rearrangement of the cards on a player’s board. This action becomes critical when a slot must contain the right number of cards—in the right order—to visit an apostle. Sanhedrin spaces advance the game’s timer. Mahane and XXXIII A.D. cards are also among the icons.

Two icons send followers to the Supper. When a Go to the Supper icon appears, players must send a follower from the location with the most followers. This is one of the game’s tensions, as more followers equals more resources, but that strength is often short-lived as they are immediately shipped out. The central table is surrounded by a grid of spaces with resources labeling each of the coordinate rows and columns. In order to claim a seat, the follower must bring the right combination. Some of the seats contain icons for Denarii, Parables, Redistribution, and the Sanhedrin that may trigger when a seat is claimed.

As a contrast, the Be Invited icon serves the same purpose, but without the need for requisite resources. These icons are more rare, and they are rather helpful. Heading to the Supper without cost is a rather lovely inclusion among the mechanisms.

The most valuable seats in the room are those directly in line with Jesus, and the various apostles—who may or may not be seated upon arrival—each carry their own arbitrary scoring value. The more valuable the seat, the more likely it will be involved in contentious swapping.

Game turns continue in this fashion: play a card, (maybe) visit an apostle, (maybe) purchase a Mahane card, and make sure you have five cards in hand. Each player board has a Warehouse area that begins as a holding tank for followers, but then increasingly becomes resource storage. As each follower is placed at the Supper, players can claim an Offering token that permanently blocks a space in the Warehouse for one endgame point.

Each player board also has an Illumination tile. Instead of playing a card, this tile can be exchanged for one of the apostolic favors during any turn. The tile is worth five points in the endgame, and it’s really hard to pass on playing a card, but the benefit is often worthwhile.

As the Sanhedrin timer moves along its track, every other space triggers a minor scoring opportunity. The active player receives the full bonus, while every other player receives half. The primary endgame trigger occurs when this timer reaches the top space. There are spaces to move the timer, but once the apostles are all seated, the marker moves at the beginning of every turn until the game ends. As a second possible endgame trigger, the game also ends immediately if a player places their last follower at the Supper.

During the game, points come in the largest portions by visiting the apostles, followed by doling out Favors and a smattering from listening to Parables and the odd card or two. Final scores come from the number of Parable tiles, Offering tokens, and leftover Illumination tiles; but the vast majority of scoring then comes from seats at the table as each row and column is scored based on proximity to Jesus and the apostles.

On the two-player mode

The two player game takes place on the backside of the board. Gameplay is largely the same, but the player decks are unique due to the addition of two actions involving the unused follower meeples.

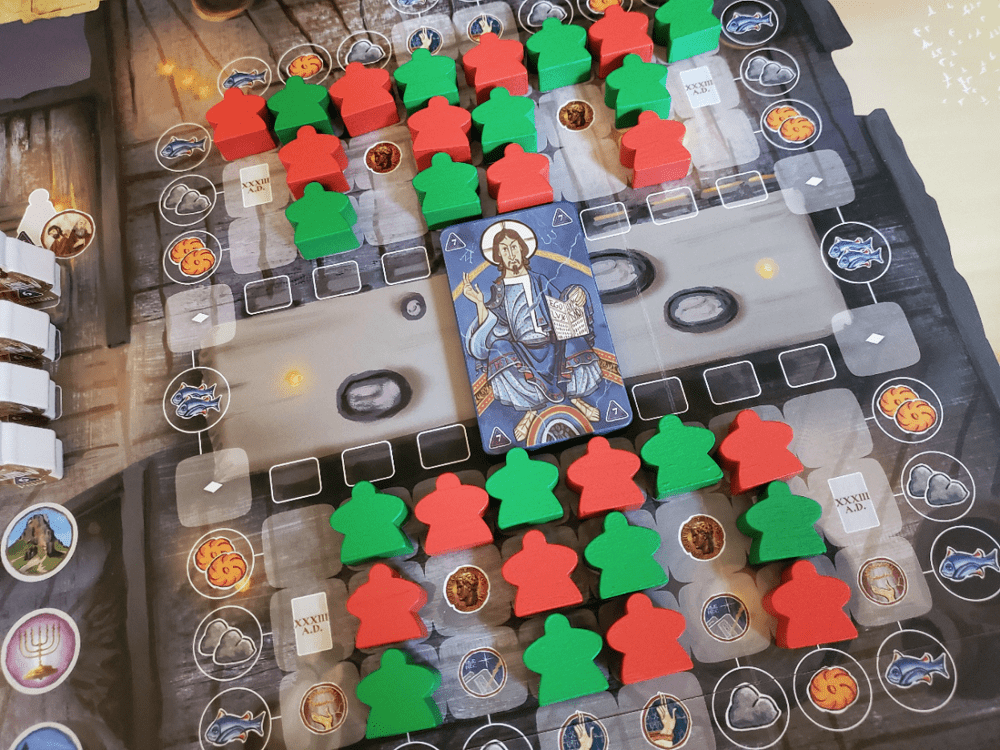

At the outset, the additional meeples are arranged at the Supper as Friendly Followers. When Sending a follower to the Supper, players can remove a Friendly Follower to their area to claim a seat according to the normal means. Later, Friendly Followers return to the board via their own action icon and trigger a score based on the number of orthogonally adjacent matching meeples. Similarly, Moving a Friendly Follower accomplishes the same scoring end, but without the intermediate step of removing the meeple.

The two-player board has an entirely different set of icons around the table. Notably, the Parables come almost exclusively from the coordinate grid. Doing Favors is not a part of the duel, which means XXXIII A.D. cards come exclusively from the grid. Moving Friendly Followers around to expose these bonuses—in hopes of being able to claim them before your opponent—taxes the mind throughout the game.

While this is a relatively simple change, the entire experience takes on a new flavor with this area management game within an area management game. The Friendly Followers provide decreasingly lucrative matching bonus opportunities as more and more seats are claimed, but until the end they are revealing boons beneath their seats and enticing particular placements around the table.

On the solo mode

Perhaps it’s safe to say at this point that I occasionally dabble in solo modes when the game is right, but I still offer the disclaimer that I am not a solo player. I wanted to see how Ierusalem: Anno Domini played out, though.

Gameplay looks a lot like the two-player experience, but the opponent is Barabbas, the notorious prisoner who was released as Jesus was condemned. The player uses both decks from the two-player experience shuffled together. Barabbas has his own deck. Where Barabbas really changes the dynamic is on the Sanhedrin track. Instead of the minor scoring bonuses of the multi-player affairs, Barabbas brings his own “bonus” tiles that radically alter the areas around the table. Each time a tile is triggered, Barabbas eliminates all of the meeples from a specific quadrant, row, or column of the Upper Room. This includes Friendly Followers and player followers, but not the followers of Barabbas—nasty tricksy. He then seats an apostle according to the image on the tile and play continues.

On his turn, each Barabbas card features an imprint of either the top or bottom half of the grid with arrows indicating his row of preference for the turn. Action icons on the card allow for the placement of Barabbas’s followers. He collects no resources, he just gets in the way where it matters most. And don’t worry, there’s a protocol to make sure he’s everywhere, even when he can’t get his top choice.

The solo experience is an exercise in forced diversification with regard to follower placement. Knowing throughout the game that Barabbas is coming with his eraser—a big one—means scattering followers about, never trusting that an entire row won’t be knocked out on a whim. Watching resources is important to enable and guard against the whirlwind that is Barabbas.

On the components

Ierusalem: Anno Domini is a pretty solid game.

From a spacing standpoint, the Upper Room is busy. There are 52 seats on the grid altogether, and they are only (if at all) marginally larger than the meeples. We’ve tried plays with them standing up and laying down. Laying down they are so tight that moving one will disturb many. It feels like when I played Operation as a kid, only with fat fingers instead of plastic tweezers (and, thankfully, no startled buzzing). Standing, they are somewhat easier to grasp and maneuver, but it’s still rough. However, and this may sound strange, when the pieces stand they obstruct the view of the coordinate resource icons. Thankfully the icons are laid out as mirror images on both sides, but it was a comment. On a similar note, the apostle meeples are large enough that it’s possible folks won’t have a clear view of the apostolic favor icons should they need access. It’s no big deal, but it might mean you’ll need more than a secretive glance to spy the whole situation in planning your next move from the far side of the table.

The components, though, are nice. I really like the classic iconographic art style on the meeple stickers—that style is about the only way I would have liked the artwork here. 180+ stickers is a lot, but there is a payoff as the various pieces are enjoyable. I’m glad Devir went with wooden resources as they give it a nice physical presence. The six-fold board is huge, but nearly every resource fits somewhere and there is still room for the player boards around our dining room table. The only partially wasted space is the northeast corner, but we stash the Offering tokens there without covering any of the Sanhedrin spaces.

The cards are decent quality and the action icons are crystal clear. Apart from there being so many, there are no difficulties parsing out the various options. The Parable tiles are chunky and I love the Latin headings.

Like I said: solid.

On the gameplay

Perhaps the most agitating mechanical aspect, but one that is reasonable, is the notion of arranging cards for apostolic visits. By design one icon will be under-represented in the bunch, and another may only appear in the second and third slots. Situations like these make it difficult to just play the cards in order…and, thus, tension is born. This is the whole idea behind the Redistribute action, but it takes a bit of getting used to. We tried one (2p) game without that restriction and used Redistribute to gather cards into the correct slot if necessary. It still worked—and wrapped up much faster. I understand the efficiency puzzle aspect, but I wouldn’t be sad about a fast and free race for sets.

The resource loop is fairly standard, but effective. The Warehouse limitation, much like the ruler in Devir’s Red Cathedral, is an efficiency restriction that is the best kind of uncomfortable. Getting followers out early is important, but it requires money, which comes by way of resources that you don’t have room for until you get your followers out. Classic.

Hand management is definitely interesting. It is quite possible to play the entire game without exhausting the personal ten-card deck thanks to the availability of the Mahane and XXXIII A.D. decks. I expected to be shuffling again and again, but I found the pursuit of a few extra coins to purchase the more potent option to be more thrilling. The Favor action feeds this loop as well by providing the most lucrative cards, making generosity even more enticing. As these cards come straight to the hand, a player might go a half dozen turns without even drawing from the starter cards. They wait as a fallback, a stock of base actions to fill gaps.

The area management is the star and it is quite enjoyable. There’s a touch of speculative placement as followers often arrive before the apostles. There’s the race for position once the apostles of highest point value arrive. There’s the constant battle and seat-swapping to be near to Jesus. All along there are desperate needs to grab seat bonuses. Despite the fidgety meeple movement as the room fills, I think the concept around the table is lovely

I prefer the three and four player affairs. Favors are sacrificial, but the inclusion of the Favor track opens up a decent strategic avenue for scoring, even as the tokens enable other players. Broadly speaking, I enjoy the unpredictable variety. Everything matters, but there is room to specialize somewhat with Parables, apostolic visits, or the seating as major scoring options. And the back and forth of seat swapping is just more fun with more players involved.

The two-player experience has received a mixture of responses. The whole Operation bit is more than partially to blame because it is evident from the word go with an Upper Room full of Friendly Followers. There’s just a lot of messy plucking and dropping, but the scoring considerations are significant, and it’s fun to watch the various colored pockets form—one more piece of the game’s narrative arc.

I was surprised how much Barabbas got under my skin in my solo outing, but he’s an interesting opponent. The first time he wiped out my work, I let out a frustrated laugh as the big picture came into focus. By the end game I had him figured out enough to lose by one point. He brings a worthy challenge and story for the single-player mode.

(A bit) On biblical fidelity

As I said at the beginning, the game exists, so I engage. I’ll now tread delicate ground for my last couple points. I am not bothered by the broad narrative at work in Ierusalem: Anno Domini. Folks chased after Jesus for the entirety of his earthly ministry for a variety of reasons. With this in view, the game makes sense. Get close—that’s the mission. There is no talk of motivation or the eternal efficacy of the endeavor. Gathering up resources in the name of not arriving empty handed is not irrational, especially when considering that there are also those followers who are invited and come in their poverty.

The most challenging theological aspect of the game is the fact that everything scores points and the aim is to outscore others. Do favors, get points. Listen to parables, get points. Visit enough places, pop in on the apostles and score points. Jesus scores me seven points? Philip six? Christianity is not a competition. Keeping score and biblical grace are somewhat mutually exclusive concepts, and there is only one champion in the true narrative. But that is the challenge of making the game at all. It is impossible to make a game of the deep truths at play when, by the book, the biblical score is settled by Jesus himself and shared as a gift.

Thankfully, I don’t believe the game is meant to offer a soteriological (on the matter of salvation) model, but rather a curious look at one of the most interesting nights in human history. What might it have been like to try to get into the room? Who would you have wanted to sit by? While it’s not a Sunday school lesson, I do believe every attempt has been made to create the playground without trampling core Christian doctrines, even if the game as designed does work best with a touch of imagination.

One head-scratcher for me is the Sanhedrin track. Considering the antagonistic relationship many in the ruling body had with Jesus and their inclusion in the events of the Passion, I am surprised the track showers so many intermediate blessings on those trying to get close to Jesus, unless it is in pursuit of information? Maybe I’m missing something.

The rulebook is chock full of Scripture to help build context, including the text of the parables on the final page. The passages are not offered as heavy-handed bludgeons, but guideposts to the story. I am thankful that everything is presented with reverence as an exploration with open doors. But obviously there are gaps; there have to be. It’s a board game—a friendly one, broadly speaking, but still.

I suppose the difficulty is categorizing the experience. It explores history, but as pure history, scholars will inevitably point out flaws. Because of the event, it touches on theology, but as pure theology, the faithful will do the same (especially given the number of traditions under the vast umbrella of Christianity). I hardly think it’s worth playing if the sole interest is in picking it apart. Why do that to your blood pressure? But I do think Ierusalem: Anno Domini is worth playing if you enjoy the imaginative exercise and you’re of the sort who think such a game might be worth creating and playing. I’m not sure I’d want to play it all the time, but I am happy to have shared the experience with some friends.

The thematic material is respectfully and beautifully presented for wide appeal. The core mechanics are engaging. There is variety in the box across all player counts. Who knows? There may be a worthwhile conversation or two along the way—there certainly has been for me. If such a game is to be made, Ierusalem: Anno Domini is made well.

Add Comment