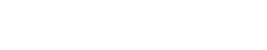

I often find myself quoting Stellan Skarsgård’s reading of the line “When is a gift not a gift?” from the 2021 adaptation of Dune. I don’t know why. It’s lodged in the folds of my frontal lobe, popping up at the strangest moments. When considering Water Dragons from HABA, for example, I find my inner self hunching over, adopting gravelly tones, and bubbling, “When is a race not a race?”

Cards and Dice

Each player controls a dragon making its way along a private swimming lane towards a nest on land. The bulk of your dragon is hidden beneath the waves, but it emerges in three sections: the head, a nebulous middle, and the tail.

To move your dragon, you roll a die. In lieu of numbers, each side has either a color or a symbol. Four of those colors correspond to spots in the card market on the board. If you roll red, you take the card on the red space. Each card moves some combination of dragon parts a given number of spaces. As you might imagine, the body parts cannot pass one another. If the full movement value of a card would move your dragon’s tail past its middle, for example, you can still select it, but the tail stops short of passing.

The two remaining sides of the die are a wild side that lets you choose whichever card you want, and a 2x symbol that gives you two points of movement. Those can be divvied up amongst your three body parts as you see fit.

We’re always looking for children’s games to develop a skill or two in one way or another, preferably as sneakily as possible, and Water Dragons gets kids thinking about probability. You’re allowed to roll the die up to three times on your turn, doing a reroll when the result isn’t to your liking. As you might expect, younger players don’t always quite get the distribution curve. The number of times while playing this that I’ve had to say to a child, “Are you sure you want to roll again?”

They always do.

Every now and then, a shark appears in the market. Though not exactly the dynamic I would have predicted, it turns out dragons are just as afraid of sharks as little humans are. If a shark crosses your path, your dragon retracts, bringing its head back and its tail up to wherever that nebulous middle is to be found. If you’ve managed your dragon’s movement well, those cards are a great way to catch the tail up to the rest of you. If you haven’t anticipated one of those cards coming out, and your head is well ahead of the rest of you? Not so good.

Race to the Fin-ish.

Water Dragons went over well with the 5-7 year-olds with whom I played it, at least for the first game. They did ask to play again, always a great sign, but they proceeded to lose interest about halfway through that second game. It may be that four players is too many, but I quickly found the game tiresome. Given how incremental movement is, it lasts an awfully long time.

My fundamental issue is this: Water Dragons never feels like a race. There’s very little tension around who’s going to get to the end first. Despite the die rolls, and despite the heavy swings that can result from a poorly timed shark, the whole thing is never particularly compelling.

The good news? This is simple enough that children who’ve played it a handful of times with an adult could easily play it on their own. That’s not something to be discounted. The wooden dragon pieces are charming, with unusual player colors that stand out boldly against the ocean-blue board. Water Dragons comes in a smaller box for HABA, but it still sounds like play, and I suspect those dragon pieces will find their way into all sorts of playtime adventures. They would have for me, at any rate.

With kids games, I try to keep my recommendations to those that children and adults alike will thoroughly enjoy. I’m not a tough sell in that area myself. If the kids love it, Exploding Kittens aside, it’s likely that I too am having a good time. With Water Dragons, it seemed like we all thought it was just fine.

Excellent review. Thanks so much!