Translation is hard. There are words that don’t exist, tenses that don’t quite carry over, and, perhaps most perilous, the vagaries that come with cultural differences. I don’t mean the offensive and the inoffensive, a matter entirely separate. I’m talking about things that sound fine in one language and patently absurd in another.

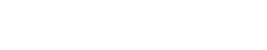

ルールの達人 doesn’t sound so absurd in Japanese, as far as I can tell. Three semesters in college and a lifetime of absorbing cultural products tells me that “Master of Rules”—I would probably translate it as “Rules Master,” personally—is a-okay. In English, though, it’s clunky. It’s clunky and uninviting.

“What do you want to play tonight?”

“How about Master of Rules?”

“Oh, I do love Master of Rules.”

It’s a Portlandia skit about board games come to life. Master of Rules sounds to me like a game with an ever-increasing rules load, an escalation of condition upon condition until finally someone caves, Calvinball by way of an ouroboros.

The reality is significantly less daunting.

Two Decks, Both Alike in Dignity

There are two decks in this box. One consists of numbered cards in several suits, while the other consists of rule cards. Each player receives four numbers and three rules. You play one of each over the course of a round, playing either during your first turn and the other during your second. The goal is to score points, of course, which you do by fulfilling the rule you played during the current round.

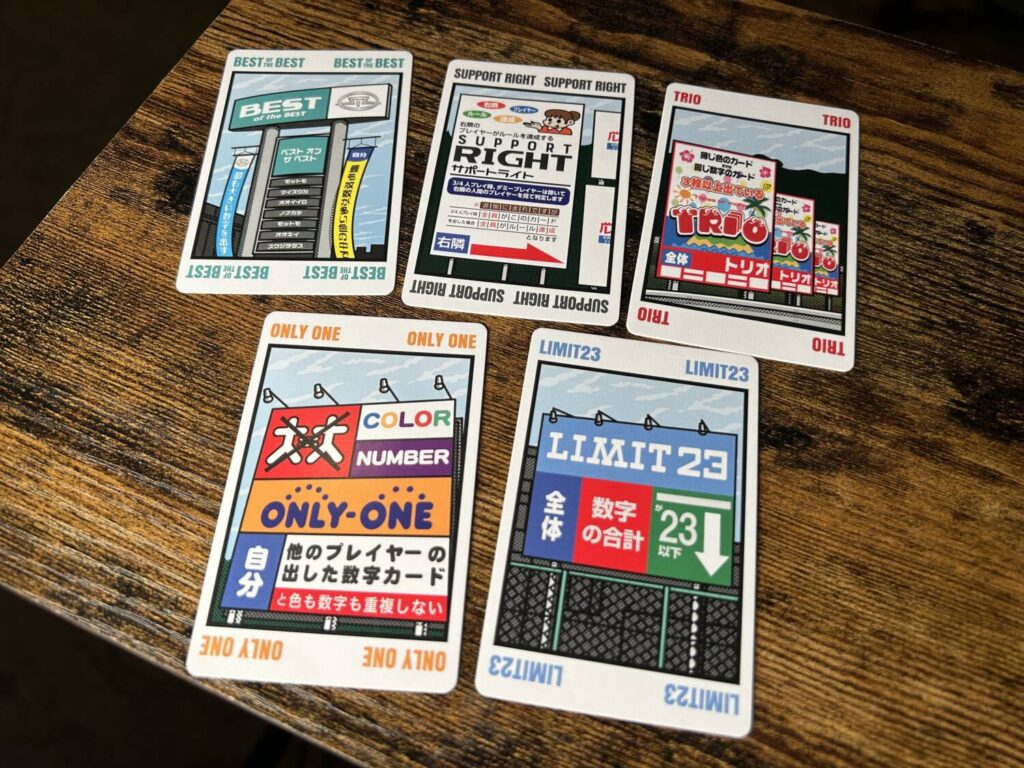

The rules are pretty straightforward:

Limit 23: All played cards have to add up to 23 or less.

Best of the Best: You have to play the highest card in the most-played suit.

Only One: Your number card can share neither number nor suit with any other card.

Trio: There have to be three cards out with the same value or suit. Yours need not be part of that.

Support Right: If the player to your right succeeds, you succeed.

You have to manage your card plays to fulfill your rule. Seems relatively straightforward, right? Well.

Timing

You aren’t allowed to play a rule that’s already out on the table for this round. That means the first turn decision to play your number or your rule is surprisingly tense. Playing your rule first means you can almost certainly play the rule you want, but you risk your opponents playing their number cards in ways that avoid fulfilling it. Playing your number first leaves you with more flexibility to respond to the choices others make, but you’re also giving them the chance to freeze you out, or to play their rules with the extra information that is your number.

Each time a player plays a card, they choose a replacement from the card market, which is reset at the beginning of each round. Keeping track of the cards your opponents take is crucial to playing well. If everyone has mostly low numbers, and you’re sitting on a pair of nines, it’s a good opportunity to play Best of the Best. Was the market full of purple cards two rounds ago, without any purples having been played since? Sounds like you should consider playing Trio.

At the end of the game, you score one point for each rule you have, as well as bonus points for having one of each rule and/or three of a rule. In the later rounds of the game, knowing what rules your opponents haven’t played can lead to a lot of fun moves born out of spite.

Oh, if you don’t have any unplayed rules in your hand, by the way, the game doesn’t punish you. That would be brutal. Instead, you reveal the rules in your hand and play whichever one you want.

The Subtle Racism of Lowered Expectations

I didn’t have much in the way of expectations going into Master of Rules. The premise as described to me—everyone is playing a different card game—was just chaotic enough to hook me out of a sense of morbid fascination. I didn’t think it would be particularly good. Instead, I was given a remarkably straightforward, delightfully focused card game, one that doesn’t feel chaotic in the least.

I have to knock publisher Hobby Japan juuuuust a bit for marketing this game as for 3-5 players. The manual itself says explicitly that the game needs 5 players. That’s the primary source of suspense around rule cards, since there are only five different rules in the game. There’s an automata in the box to adjust for 3 or 4, but I don’t have any interest. You need all five players, you need all the card choices to be intentional. That’s what makes this great.

Master of Rules gets better with familiarity. It is sharp and tactical. It is also wonderfully compatible with table talk. “I’ll play an orange card if you play a 7,” “I won’t break your rule if you don’t break mine,” etc. This is not a card game for everyone, but I thought it was great. Give it a political theme—trying to get people to fulfill your agendas—and change that name, and my god, we’re onto something.

You (and the rest of the good people at Meeple Mountain) have written some great reviews. None have spoken to me quite like the last few lines of this one: “Give it a political theme—trying to get people to fulfill your agendas—and change that name, and my god, we’re onto something.”

This game. Yes. Please. Somebody needs to shut up and take my money.