During my recent trip to TantrumCon, I ran into Jay Bernardo, the marketing manager with Bezier Games. We hit it off, and that led to a six-hour binge featuring games all night and lots of smack talk. (If you have not spent time with Jay, you need to get on that stat…the guy is hilarious.)

Jay also took the time to show me Sandbag, designer and Bezier CEO Ted Alspach’s latest game and what I think is his first trick-taking release. (Bezier has dabbled in trick takers before thanks to the release of the deluxe edition of Cat in the Box.) Jay was kind enough to provide a review copy after our first play, so I got the game in front of my Chicago game groups to see how the game played with other audiences.

During my first play of Sandbag, we got a single rule wrong, so correcting that did make a difference in successive plays. Still, I was surprised that this one was more of a curiosity than an outright hoot like the game’s rules seem to suggest. I don’t think that is a flaw, but the game does have a high rules overhead for such a simple concept and I wonder how this will play with broader audiences when it hits the market this summer.

Swappity Swap

The goal of Sandbag is simple: score the fewest number of points.

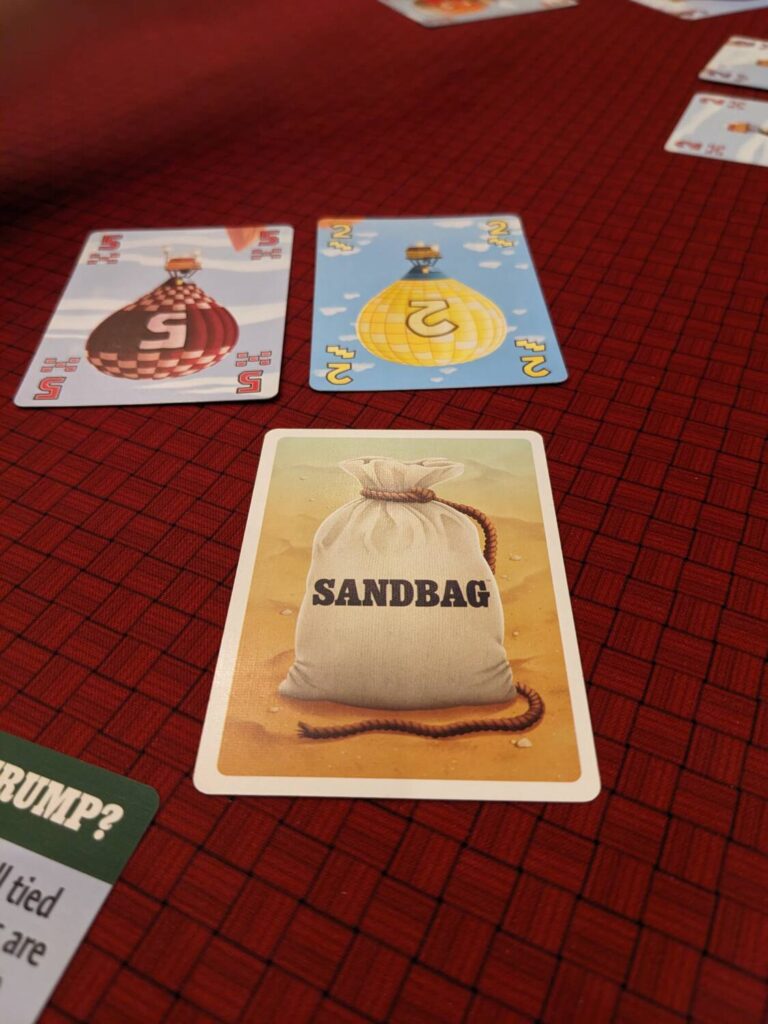

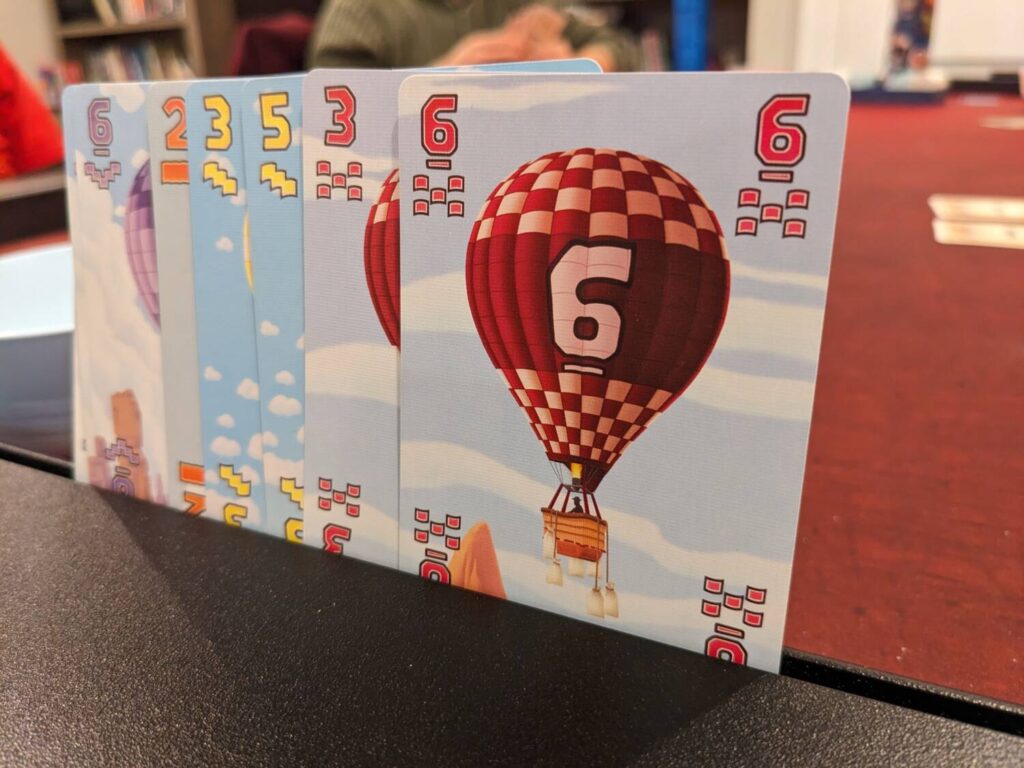

Across three rounds, players will try their hardest to not win tricks…or, to win tricks that feature one of the negative-point Rocket cards featured in small supply within the deck. The Sandbag deck features balloons in five suits, numbered 0-10, along with five Rockets that are either value negative five or negative seven, depending on the player count.

Once the entire deck is dealt, each person picks two cards from their hand to pass (one to each of their neighbors). Usually, these are the highest cards in your hand, although these might occasionally be the Rocket cards that are better to win than to play as one of your hand cards. Then, with a complete hand of cards, players will place one card face down as their sandbag for the round, a card that cannot under any circumstances be eligible to win a trick. Two more cards from their hand are placed face-up in front of each player from their hand. This is the “basket”, usually with low values because any face-up basket cards that remain at the end of the round count as points equal to their value against that basket’s owner.

Sandbag uses a cool trump card system based on the face-up cards in each player’s baskets. The suit with the highest number of cards is declared the trump suit. If there’s a tie, the value of the cards in each suit determines the trump. And even during a trick, the trump suit could change thanks to the game’s swap system.

Are you still with me?

There are a lot of rules around this part. The active player can swap a card from their hand with a face-up basket card if any of the following are true:

- It’s the opening play of a trick

- A player has one, or zero, cards of the lead balloon suit in their hand

- They have one of the lead suit cards in their hand but they want to play the lead suit by swapping a card out from their hand for a “better” (usually, lower) card from another player’s basket. This turned out to be pretty useful when I had exactly one card from, say, purple, then purple was led, with a number that was lower than the card in my hand, but I saw a purple on the table that was lower than both my hand card and the led card, so I did the swap.

Swapping a card from a player’s basket is great news for the other player, because the replacement card is face-down and only counts as a single point against their end-round score. That could mean that an eight-value card is suddenly only a point—key since you want to score as low a total as possible.

All the above information should give you an initial sense of one thing: Sandbag is rules-heavy but encourages chaos.

You want to score low, but thanks to the available shenanigans, you might win a trick with a non-trump zero card in a round where you lead with a zero, two other players use their sandbag—which, again, is guaranteed to not win a trick—then two other players throw off (“sluff” or “slough”, in trick-taking parlance) to ensure that the led suit wins the trick. In fact, this happens so often that in each of my plays, someone always curses the sky as they take multiple tricks by playing the lowest card in a suit in a round.

So let’s give Sandbag this much: it’s certainly different. This is especially true when swapped basket cards lead to the trump changing during that trick, sometimes twice on the same trick! But, at the end of the day, all I care about is this: is Sandbag fun?

Sandbag is Fine

For a trick-taking game, Sandbag is hard. It’s not overly difficult…I mean, look, I played Voidfall 14 times last year, so I’m cool with hard.

But it IS hard for a trick-taking game. The rules explanation really snowed me during my first play, and even teaching it to other players, it’s a beast for a trick-taker. (Spades, this is not.) The player aid and the rulebook don’t do Sandbag any favors, either. Like other Bezier games I have owned (including Cat in the Box and Maglev Metro), the rulebook isn’t great, so I’m thankful I got to learn this from the Bezier team.

The double-sided player aid is somewhat worthless beyond the swapping rules, and even then, I was surprised how many questions arose during play regarding swaps. Sandbag is not the cleanest of designs.

Getting past those hurdles, Sandbag was ultimately OK. I love the dynamics that can change during a trick. I loved watching players get hosed as they won tricks with low off-trump cardplay, even when it happened to me. I like the catch-up mechanic for players who have at least 10 points by giving those players the opportunity to play more sandbags in the following round. I haven’t seen someone come back from a large deficit yet, but it makes a player that is probably going to lose feel slightly better about their situation.

The wow moments come when players are holding Rockets and hoping to pass them off to players that aren’t already in the lead, which can be challenging. It’s interesting to try and work around a bad deal featuring lots of high cards, particularly if they are concentrated in one or two suits. But these aren’t big wows…more like little ones.

Sandbag, even in victory, never left me feeling amazing about the experience. It also plays in about 30-40 minutes with five players, which feels long for a game that sometimes leaves one player in a strong position after the second of three rounds, leaving the last round to serve as target practice as players try to gang up on the leader to force them to take tricks. (Tricks are always worth one positive point per card in the trick, so if no rockets are played in a trick with five players, each trick is worth five positive points for the person who wins it.)

The production here is fine; it’s a deck of cards with simple art, so it does the job even from a distance across the table. The rulebook could use some editing work because 21 pages is too long for a trick-taker. The main offender in the rulebook is the lack of picture examples of how swaps work. I got around this thanks to being taught the game before seeing the rulebook, but after getting my own copy, I was surprised that this came out in the way that it did.

I’m happy to play Sandbag at the suggestion of others, particularly at lower player counts. But this was an otherwise average experience.

Add Comment