Fortitude was the codename for one of the major Allied operations of World War II, with field armies attacking in Norway and Pas de Calais. The Japanese ambassador to Germany believed, before the operation, that forces would then strike across the Strait of Dover. The scale of Operation Fortitude was massive, one of the largest in military history.

You may not have heard about Operation Fortitude in school, and there’s a good reason: it was a dummy operation, made up whole cloth by Allied forces. Operation Fortitude was intended to draw Axis forces away from Normandy in preparation for D-Day. It worked.

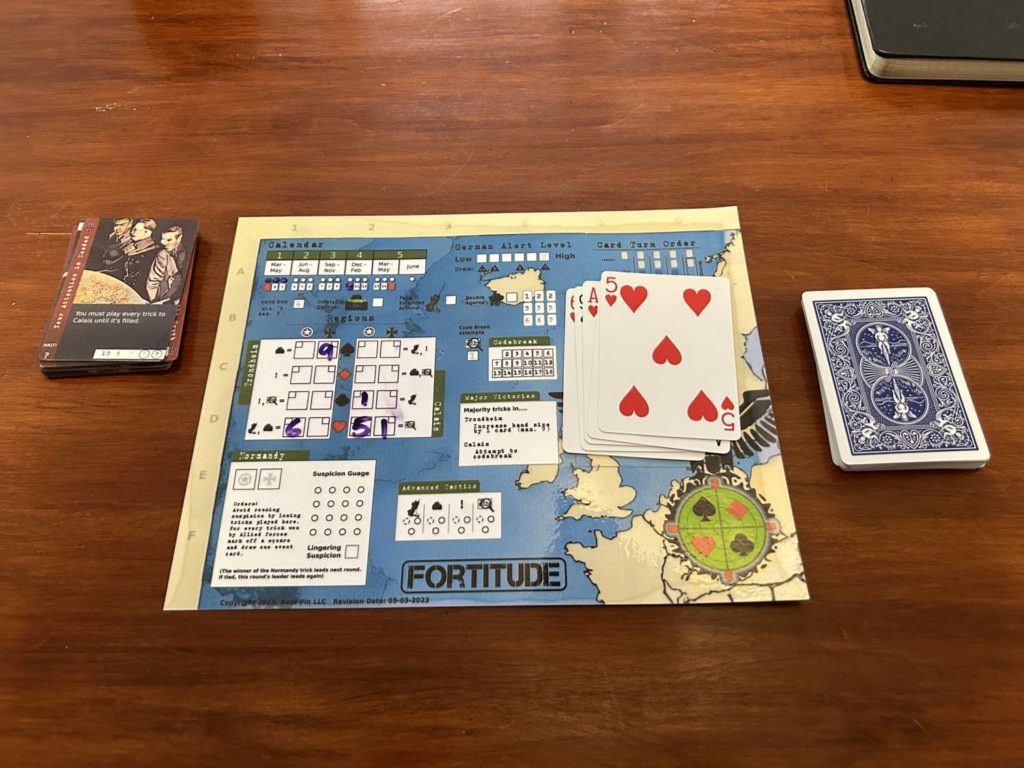

Fortitude the game, themed after the operation, bills itself as a solo trick-taker, a fascinating proposition I’ve only encountered in For Northwood!, which I haven’t had a chance to play yet. I was immediately hooked by the idea. How do you translate the muddiness of a trick-taker, the high reactivity of the form, into a solo experience?

Mission Briefing

The goal of the game is to make your way, month by month, through 1943 and into the summer of 1944, the launch of D-Day. You and the German AI opponent take turns playing cards to nine different Tricks, evenly split between fronts in Trondheim and Calais. Each front contains four Tricks, one for each suit in the deck, and you are only allowed to play cards to matching locations. If you don’t have any cards left in your hand that allow for a valid placement, you have to discard one and mark off a location as a loss.

You are trying to win as many Tricks as possible, with the exception of the single as-yet-unmentioned Normandy trick, which you want to lose. Tricks represent military engagement, and a strong Allied presence in Normandy would attract unwanted attention. Win a few too many of those, and you’ll be out of the game.

For whatever it’s worth, I wouldn’t describe Fortitude as a trick-taking game, though I can see why designer J.L. Reid categorizes it as such. With the going trends in board gaming, trick-taking is good branding, and it does make use of direct face-offs between cards, where the value of the cards determines the winner.

The tensions present don’t feel much like a trick-taker to me. Part of the issue, I think, is that I have a limited hand, but my opponent doesn’t. They have the full breadth and width of the draw deck available. Combine that with the fact that the bot is unencumbered by suit restrictions, and it just feels like dumb luck, for the most part. Not entirely, but for the most part.

Rather than a trick-taker, I think Fortitude is much more in keeping with a flip & write. I know that’s the genre we all love to harp on. There is nothing inherently critical about that statement for me, it’s purely an observation. It’s just that, if I expect chocolate ice cream and I’m given mint, I’ll be at least surprised.

I Was in the War

My picked nits regarding genre aside, I didn’t have a very good time playing Fortitude. The main issue is the round structure, and the way that commingles with the months. A round doesn’t equal a month. One hand equals a month. It is possible, and even likely, that either one round will encompass multiple hands, or one hand will extend just past the boundaries of a given round.

There is maintenance to be done at the end of each hand, mostly advancing the month, and at the end of each round. I found myself in a near-constant state of admin, and in an absolutely constant state of losing my bearings. Reid, who did a great job designing the layout of the player sheet, included a chart in the upper right corner to help keep track of where you are in a round, but I had to consult it at least once per hand, if not more, and that takes me out of it. I struggled to find a state of flow. There’s no point at which the mechanical process of running the game vanishes, leaving you alone with the decision space.

I have ended no fewer than four different games of Fortitude early, because I was unable to figure out where I was in the round. I also consistently forgot things during the various admin steps. None of them huge, and many to my benefit, but I’ve played enough games at this point to trust that when something still doesn’t feel right after two readings of the manual and seven or eight plays, I’m not the problem.

There are elements of Fortitude that are surprisingly thematic. If a hand ends—again, I had to take a moment to remember whether I wanted to say “hand” or “round” here—with any tricks by either side unanswered, it creates an Extended Engagement. If the opponent hasn’t responded by the end of the next hand, a penalty is incurred. In the case of the bot, that will never happen. They prioritize responding to Extended Engagements. That, however, is a canny replication of the ways in which allocating armed forces to a given location will cause that location to be a focal point for your enemy. It’s clever.

I also enjoy the tension that comes with trying to balance raising your hand limit, made possible by winning more tricks in Trondheim than Calais during a given round, against wanting to get through the months as quickly as possible. There is stuff to like here. For me, though, across multiple plays, luck proved too decisive early in the game, and it was an uphill battle to have a good time from there.

If you’re curious to try Fortitude, I would encourage you to do so! It is available to back as a print-and-play, so it’s not as though it will break the bank. There are things about this design that I find very clever, even if they never cohere for me. The design feels underdeveloped, but Reid will be making all future iterations available for free to people who back the project now, so there may yet be changes. This is by no means a bad design, and I love what it’s trying to do. It’s just not quite there.

Add Comment